Exploring the visual and literary dialogue between ceramicist Edmund de Waal and painter Giorgio Morandi, a major exhibition of work by the two artists opened at Artipelag in Stockholm April 7. The show features 50 paintings by Morandi and 30 works by de Waal, including his series of nine suspended vitrines called atmosphere, first shown in 2014.

But it's not ceramics that unites these two artists here, but rather the encouragement of mindful viewing and contemplation. Giorgio Morandi (1890–1964) is one of the great protagonists of modern Italian art and has assumed cult status within circles of art connoisseurs. Transgressing generations, Morandi continues to fascinate artists, authors, poets, designers, and photographers to this day. You can also add filmmakers and presidents to this list—Federico Fellini's classic La Dolce Vita is one of the more illustrious examples, as is Barack Obama’s inclusion of two Morandi paintings in the White House art collection.

RELATED: A Look at Sterling Ruby's Grim Ceramic Sculptures

In the exhibition, de Waal's new works include another hour—a collection of six freestanding towers containing porcelain vessels—and another homage to the square—five vitrines containing blocks of white alabaster and gilded porcelain tiles. De Waal has also created a handwritten text piece, spanning the gallery walls. The exhibition will be accompanied by a lower floor library room where visitors will be able to draw, write letters, and read the novels and poetry that have inspired both artists.

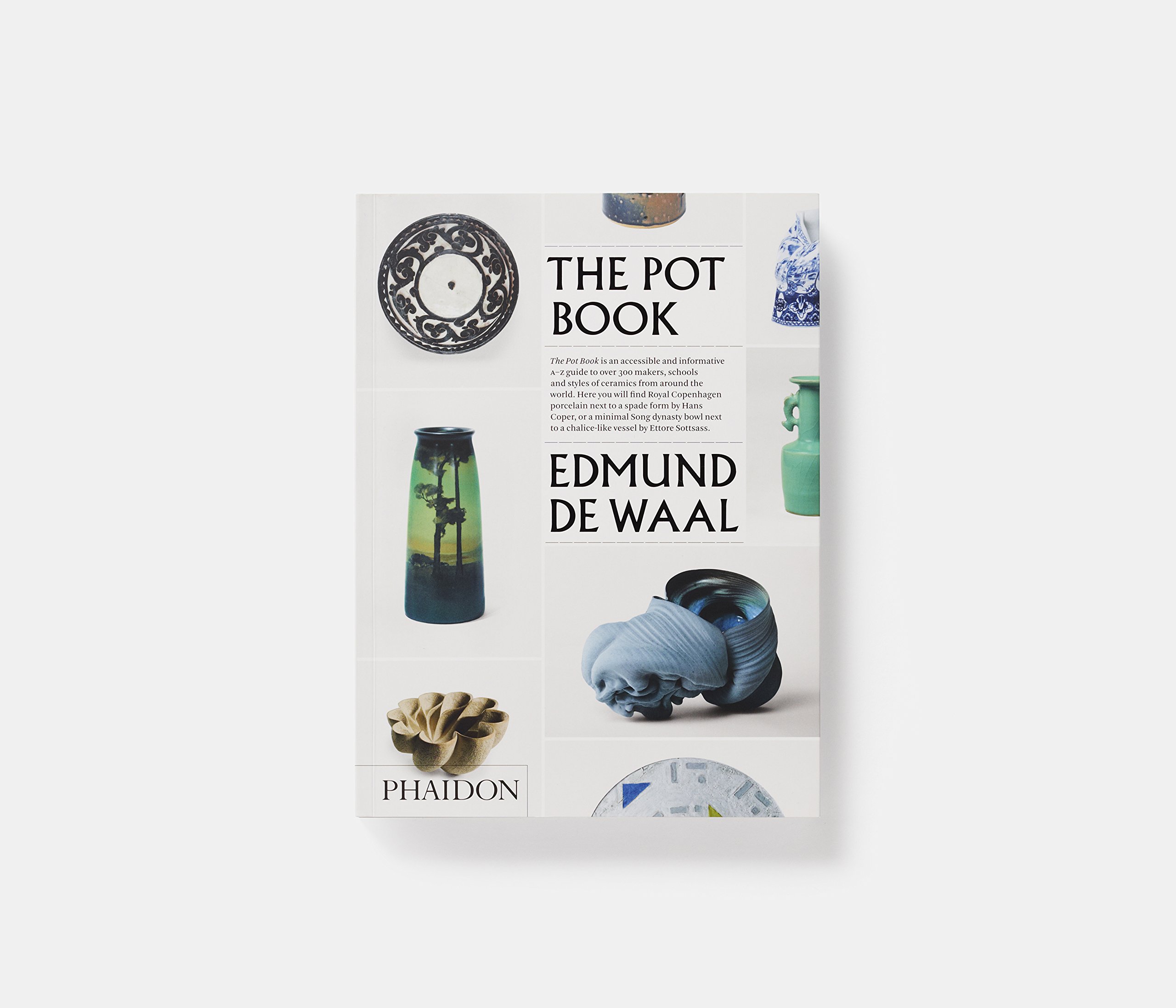

Beyond being a renowned artist and ceramicist, de Waal has quite the way with words. In 2010 he published a prize-winning memoir, The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance, which explores history of de Waal's Jewish ancestors by re-tracing the passing-down of a collection of 264 Japanese netsuke (or miniature sculptures form the 17th century) through generations of family members before ultimately settling with his great-uncle living in Tokyo. The White Road, published in 2015, recounts the artist's journey in unearthing the history of porcelain, leading him to its birthplace in the hills of China to England, his own birthplace. His coverage 300 unique vessels in The Pot Book, was published by Phaidon in 2011.

But if there's one subject the artist and can write about most eloquently, it's his relationship to his own work. "Some objects feel like nouns," the artist writes, poetically describing his working process and it's relationship to the written language. De Waal elongates the lineage of important artist writers like Ad Reinhardt and Donald Judd, adding a whole new dimension not only to how we view his work, but to how we understand the objects that surround us. Here, excerpted in full, is de Waal's artist statement published in Phaidon's Edmund de Waal monograph, in which the artist muses on his craft.

...

You take an object from your pocket

and you put it down in front of you and you start.

You begin to tell a story.

I

I make porcelain. I make my objects out of porcelain. I sit at my wheel. It is low and I am tall. I hunch. There is a ziggurat of balls of porcelain clay to my left, a waiting pile of ware boards to my right, a small bucket of water, a sponge, a knife, and a bamboo rib shaped like a hand axe in front of me. I have a cloth on my lap to wipe my hands. There is music. I pick up a ball and throw it into the center of the wheel. Today, like yesterday and like tomorrow, I am making nothing grander than a cylinder. Barely a vessel, more a sketch of a pot, an inside and a straight profile, the merest impression of my hand and then my impressed seal. All those iterative movements of arm, wrist and hand, time after time after time. I am making a series of volumes, contained spaces: each vessel is a breath, and I am counting time.

I turn, and there are my boards of porcelain vessels, still damp. They gleam softly. And then I ask myself, which story shall I tell? What is tellable and what is untellable? What do I pick up and where do I put it down?

As I both make pots and write, there is a strong, unstable relationship for me between objects and words and storytelling. They do not map each other as experience—I don't make an installation to enact something I've read or written. It is more that they sit near to each other in my life and spill across. When I write a phrase or a sentence, or a page or a chapter, the writing has such a strong shape and weight to it that the act of writing feels close to making itself. There is the way in which stories start over, and repeat, the way that phrases and images embed and re-emerge. You pick up and try again, shuffle words back a bit, light something a little better, lengthen the gaps between sentences to allow for attention to come and go. And with objects—porcelain vessels, for instance—it is possible not only to sound them, name them and make sense of them through language, but to see their kinship with words themselves. Some objects feel like nouns, words with what the poet and artist David Jones called "haecceity," a sense of their physicality, shape and weight. They have a self-contained quality, a sense that you could put them down and they would displace the same amount of the world around them.

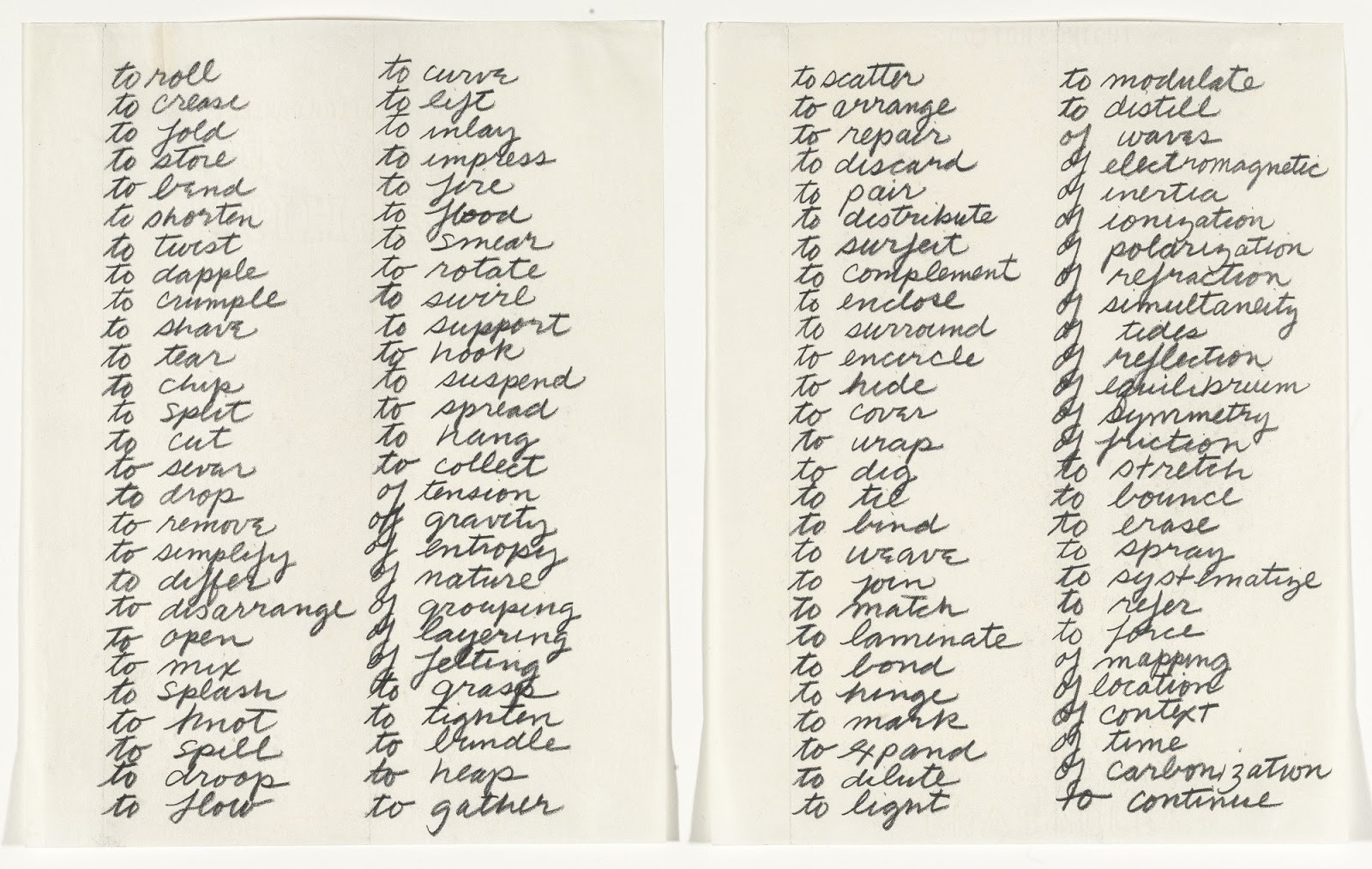

Other objects feel contingent on the world around them. These small vessels, a series of seven movements from throwing the ball of clay—five ounces of plastic white porcelain onto the revolving potter's wheel, centering it, opening it up with a thumb, five pulls to widen and straighten it to its four inches of height—aren't nouns but transitive verbs. They exist, like Richard Serra's listing of verbs, as a field of possibility of change, states of becoming something other.

Richard Serra, Verb List (1967–68)

Richard Serra, Verb List (1967–68)

Then there is the space around objects and the space around words. A simple pleasure in poetry is the spatial systole and diastole between words and page. The first sight of a poem gives you the sounding line, the congestion of syllables, the openness of caesura, the seriality of stanzas. You see it and hear it and feel it all at once. And then you read and it slows down, read it aloud and it becomes different in space, alters in the space it takes up in your mind. Some short poems—a haiku, a William Carlos Williams page, a fragment of Sappho—seem to suspend themselves on a page like sounds in air and almost demand a physical response. Reading begets pots, starts a thrum of ideas that ends in an installation. The different timbers of texts—a page from the Talmud, a palimpsest, Peter Quince at the Clavier, the Narrow Road to the Deep North—all offer possibilities to me as a maker of objects.

II

When I see my pots finished, in rows and clusters just out of the kiln, glazed, their bases rough from the firing, settling into themselves, they still seem a bit lost. For an hour or two after they emerge and while they are still warm they make sounds, as the glaze and body get used to each other. The pots feel that they have not yet reached their place in the world. In their random disposition on the table in my kiln room there can be an energy from happenstance: one bowl stacked inside another so that one edge crests another, three jars next to another in a familial huddle; the suggestive start of a phrase.

These pots are homeless. Objects need a sort of shelter in which to be. So I think of a box, black lacquer, lead-lined and dense with shadows, or a metal girder of red as long as a long line, or a white shelf on which to stack and space different kinds of vessels until they achieve an uneasy balance. Or they need their own building. Why not start with the objects and make a room in which to hold them, a space where the light comes through porcelain, hold them in the air like thoughts or clouds? A shelf is an open line, just as a vitrine is a kind of page. A shelf can act as a pair of brackets, objects can sit like the "five stanzas stalled in brackets," to borrow Anne Carson's phrase of a poem of Paul Celan's.

Where shall I put this jar? Above you in the attic where your most treasured and most problematic objects are consigned? Below you in a vitrine sunk into the ground, so that it is chanced upon? It matters, because where you find things in the world, how near you are to them, if you can touch them or not, is as much part of the language of objects as their color, their use.

Edmund de Waal, in time, II (2017) © Edmund de Waal. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian. Photo: Mike Bruce.

Edmund de Waal, in time, II (2017) © Edmund de Waal. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian. Photo: Mike Bruce.

In my opaque vitrines, objects move between profile and dimensionality, blur into a haze and come suddenly into focus. Which is how memory works, of course, shimmering like a mirage heralding us towards the wrong places. They are nothing but a failed eye test, said one critic, crossly. This holding back is not a retreat from the world, not an attempt on gravitas through obscurity, not a greying varnish to smoke over the details and make it old. I dislike manufactured obscurity. I use this blurring because it is a more accurate means to keep objects in flux than having them under museum condition lights, pinned in an airless box. Clarity can delude. There can be more lucidity in the shadows. They have what Keats called in a marginal note in his copy of Milton's Paradise Lost "A sort of Delphic Abstraction a beautiful thing made more beautiful by being reflected and put in a Mist."

This opacity also has the effect of slowing me down. There is an equivalence in this with a sculptor taking a photograph of his own work—a way of pausing work to look at it more candidly. I love the flare of light across a Brancusi image of X, Cy Twombly's piles of junked goods in a yard sale are stilled lives, on their way to his distillations into sculpture.

But my groups are not Still Life. They are not a recreating of other artists' depictions of vessels. I love Zuberan and Morandi and Chardin, but my work is not a re-staging of stagings of pots. They are not translations.

Things can be stilled, without stopping.

III

And then a name.

I love the idea of a whole opus sorted entirely by number: a Modernist list of numbers as cleansed as a Mies pavilion. Untitled #734, Untitled #735, counting down a life's work—but it is not quite me. When I first moved out from under the shadow of Leach I was uneasy about titles; the claiming of names for pots seemed hubristic. Few had done it, and the titles were either grandiose or unbearably effete. But letting a group go without a name seemed shabby, and my two favorite masters of titles, Howard Hodgkin and Lydia Davies, seemed able to name pictures and stories and not close down their meaning. So I started, very cautiously, to name.

A title is a sort of letter of promise in a pocket. Sometimes a title brushes alongside a remembered view of a Dutch interior of a church, or is a conversation overheard, a line from an inventory, a favourite melody, a street. Sometimes it is a provocation: the claiming of a shared space with someone I care about. Sometimes it is a stone thrown in the opposite direction to distract attention. Giving a work a name is the start of letting it go, making a space to start again.

IV

All this is the gamble of making fragile objects out of porcelain and placing them near each other and inscribing a name in the air over the whole enterprise. Paul Celan once described the task of the poet as "measuring off the area of the given and the possible." It is a beautiful description of a space in which to think and work.