While painters like Louise Fishman—whose 1973 series “Angry Women” was among the first to bring gender and sexual identity to the forefront of abstraction—have long been interested “expressing” something beyond formalist discourse, it’s certainly the case that even today much of the conversation around Abstract Expressionism surrounds a few select, machismo artists, like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. An upcoming exhibition at the MoMA, “Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction” is the most recent example of the current interest in setting the record straight by highlighting women artists who changed the face of art in the mid-century—beyond the token few who’ve gained major recognition. Often overlooked is the fact that the very gallery that showcased Abstract Expressionism in its early, most revolutionary days, was run by a lesbian artist, Betty Parsons. In this 1994 essay excerpted from Phaidon’s Art & Queer Culture, art historian Ann Gibson examines the legacy of one of the most influential people in the history of postwar American art, and why it’s important that we bring her into critical discourse.

...

Lesbian Identity and the Politics of Representation in Betty Parsons’s Gallery

Abstraction is rarely approached in terms of gender, in fact, it is usually considered to have escaped such constraints. And certainly it has seldom been analyzed in a lesbian perspective. It is a striking fact, however, that just before mid-century in New York, a type of art characterized as heterosexual and male—Abstract Expressionism—and recognized as the major abstraction in its time, appeared to emanate from a gallery run by a lesbian—Betty Parsons. Parsons also showed art that was not “Abstract Expressionist” a fact that indicated to some critics and even some of her artists that her standards of quality weren’t strong or consistent enough. I would like to argue that both her advocacy of the art that became Abstract Expressionism and of art that did not issued from her belief that difference superseded “quality.” Or put another way, for her, difference—stubbornly defended, even pursued past the point of practicality—was the quality she valued most highly.

Now, difference, whether it is between realism and abstraction or loving someone of the same or other sex, is to intrinsically oppositional or hierarchical. What makes difference into opposition are often acts based on a desire to make one object, mode, or person superior to another. If power is developed when one group of people direct the actions of another group, it is necessary to specify how one group differs from at the other so that the group in power can define itself. In the case of sexual difference this has meant drawing on distinctions that form the web of relations that have empowered some sexualities and disempowered others. In the case of realism and abstraction it has taken the form of arguments about how art best represents experience. To do as Parsons did—to favor what was different for its own sake, was to short-circuit power plays based on the preferences that calling something “different” facilitated.

When the National Gallery opened its new East Wing in 1978, the critic John Canady noted that 10 out of the 23 artists represented had been given their first one-man shows in Betty Parsons’s gallery. In addition to Jackson Pollock and Adolph Gottlieb there were Mark Rothko, Clifford Still, Barnett Newman, Hans Hofmann, Ad Reinhardt, Richard Pousette-Dart, Joseph Cornell and Bradley Walker Tomlin.

By the end of the third quarter of the twentieth century, it seemed as if Betty Parsons had launched Abstract Expressionism single-handedly. But if Abstract Expressionism as it has been presented until recently was an all-male, all-white, heterosexual movement, it needs to be said that Parsons also gave one-person shows to a number of artists who did not fit those parameter and have yet to achieve the renown of many of the named above. As noted above, some were women. Of these at least one, Sonia Sekula, was a lesbian. Parsons also showed men who, although not out in today’s sense, were understood by their closer friends in the art community to be devoted to their male partners; these included Alfonso Ossorio and Leon Polk Smith. She showed Forrest Bess, too, whose visionary mysticism including gay, scatological and (eventually) transsexual images and themes displayed form and references in some ways more extreme than the subjective biomorphic of much Abstract Expressionism.

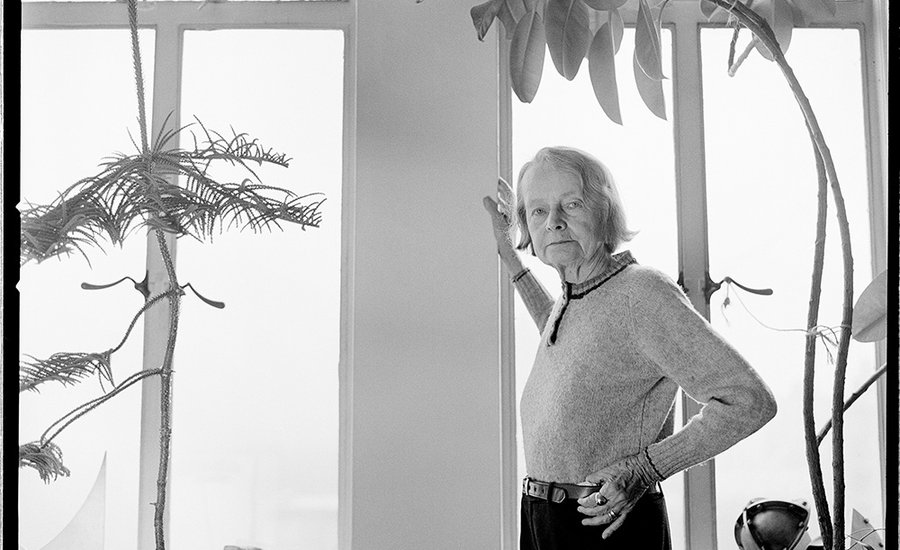

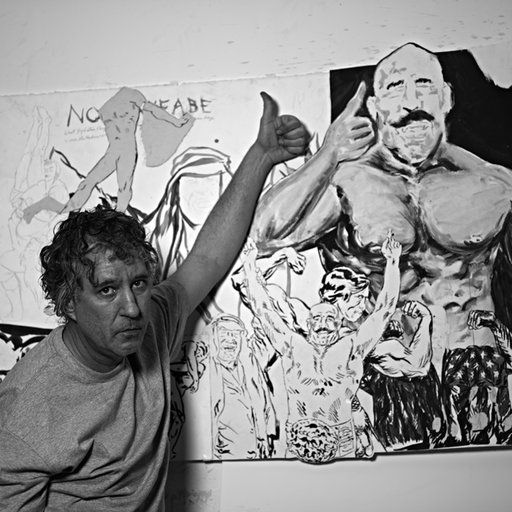

Betty Parsons stands outside her gallery

Betty Parsons stands outside her gallery

As noted above, Abstract Expressionism has been characterized as a notably male and ostensibly, at least, heterosexual male affair. Rudi Blesh’s description of these artists in his book, Modern Art USA, Men, Rebellion, Conquest, 1900–1956 reads now as a parody. But it was not intended that way, nor initially received as anything but high praise:

"They will be long remembered as a remarkably rugged lot, with minds as well muscled as their bodies (Time calls Pollock “The Champ”). They are built like athletes, and some of them, like Pollock and De Kooning, paint like athletes. If pictures could explode, theirs would, so grimly by the force of their wills have they compressed their dual muscularity onto the canvas. If any group can ever force our museums and collectors to accept American modernism, this is surely the bunch to do it."

In the thirties and forties it was generally assumed that women without husbands and children were neurotic and unfulfilled, even though they themselves may have thought they were having a fine life.

The conviction that women could be psychologically healthy only if they were wives and mothers pervaded the arts as it had other fields, establishing a polarity between the focussed, unified potential of the artistic male psyche and wast was constructed as the necessarily fragmented female artist, split between the demands of home and professional life.

Recognizing the male valence of the atmosphere of Abstract Expressionism, it seemed to Gertrude Barrer—a heterosexual woman, with children, whose abstract expressionism has yet to find its place in the history of that era—that being a gay man was not a disadvantage for an artist, but that being a woman, straight or lesbian, was. A number of closeted gays were in positions of power, she recalled, and gay men could pass as straight when necessary. Although some might take issue with the idea that being gay and male was no problem in the arts, perceptions of insufficiency were particularly easily activated in the case of sexually active lesbian women. Sonia Sekula, for instance, showed paintings and drawings that were both abstract and expressionist with Parsons from 1948 to 1957. Although her work was well-received, she was seen as unfortunate, partly because she was psychologically unstable, but partly because of her sexuality.

In an era where properly feminine women were supposed to subject themselves to masculine needs, there was, however, also an upside to lesbian identity. If gay men were belittled as “les than” heterosexual men and therefore comic or neurotic in a binary sexual system that constructed gay males as feminine, lesbian women were “more than” heterosexual women—that is, more like men. Men in dresses were funny; women in pants were real artists. “The lesbian world was much quieter then,” according to Alfonso Ossorio, “although everyone knew it was there. It was chic to be a lesbian. Priscilla Park, the head of Vogue, was a dyke. The art world was riddled with rich young queens.” As poet and painter Elise Asher observed of lesbianism in the forties, “compared to other women, lesbians had force and aggression when they go together—since women had to insist more, this was an advantage. Lesbians were living for themselves. They didn’t need that male affection.”

If lesbian sexuality’s most valuable political potential is its refusal to let male power determine female desire, then one of its most notable loci at mid-century was Betty Parsons’s gallery. Parsons’s “giants” as she called them—Rothko and Newman particularly—were eager to guide her in her exhibition and sales policies. As early as 1949 some of her more prominent artists (Newman, Still, Pollock, Rothko) urged her to abandon most of her other artists to concentrate their (the Giants) version of abstraction. In 1951, led by Barnett Newman, these men gave her an ultimatum; get rid of the other artists or we will leave.

“I was present at that extraordinary meeting,” recalled Alfonso Ossorio. "Where seven powerhouse artists were thinking of leaving Betty, they presented their ultimatum: Either you cut down on the frequency of shows and give us some sort of assurance—a contract of some kind—or else we’ll just have to leave you. Betty said, “Sorry, I have to follow my own lights—no.”

Lee Hall, Parsons’s biographer, recounted a somewhat different version of this meeting, attended by Pollock, Rothko, Newman, and Still in early 1951. “We will make you the most important dealer in the world,” Parsons recalled Newman’s telling her. “But that wasn’t my way,” Parsons said. “I need a larger garden.” Parsons’s relations with her artists were multifaceted. “Betty promoted the men more actively than she did the women,” reflected Jeanne Miles, an artist whose painting is best known for its contemplative geometry. “Betty’s being a lesbian didn’t mean that she was pushing women’s work. She thought like a man, in a way. She liked having women around. But she was not going to break her head against the wall for women artists. Men were in a position to do a lot for themselves.” Parsons’s obvious enjoyment of her artists and her simultaneous refusal to permit them to determine her gallery’s direction provides an example of a woman who refused to let masculine insistence fashion her desires or determine her program. Parsons supported her gallery not only be her artists’s sales, but also through the financial assistance of a network of women friends. A painter herself, Parsons resented the implication that the men’s work was so important that the other artists she showed should be discarded.

Some of the artists whose representation by her gallery Parsons had no intention of disturbing included Hedda Sterne, Sonia Sekula, Maud Morgan, Adeline Kent, Buffie Johnson, Jeanne Miles, Perle Fine, Anne Ryan, Sari Dienes, Day Schnabel, and Ethel Schwabacher. As the reputation of her gallery grew, Parsons was increasingly discreet about the fact that women held the central place in her affections and indeed, provided her most valuable business connections. Worried that she would be identified as a lesbian, she told Hall, “You see, they hate you if you are different; everyone hates you and they will destroy you. I had seen enough of that. I didn’t want to be destroyed.” But neither did she have any intention of caving in.

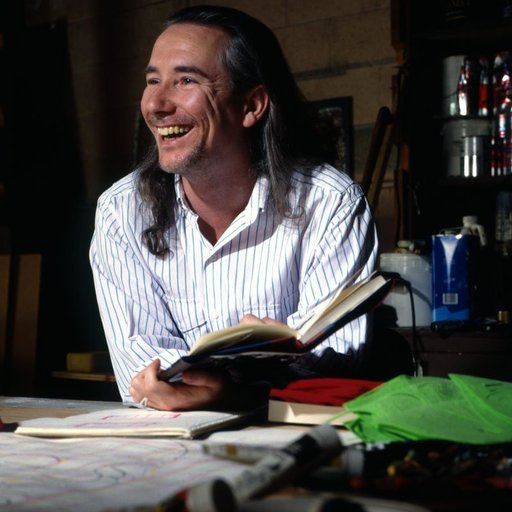

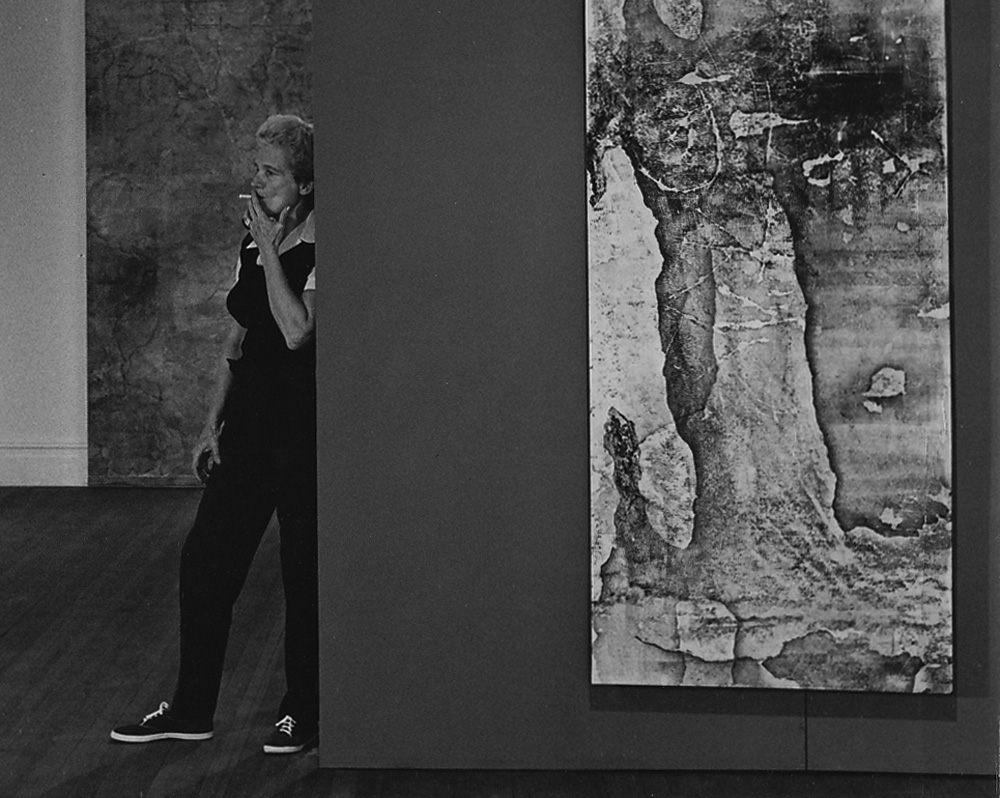

Sari Dienes smokes during an exhibition of her paintings at Betty Parsons Gallery

Sari Dienes smokes during an exhibition of her paintings at Betty Parsons Gallery

Betty Parsons’s own sexuality was not exactly a secret. She had affairs and liaisons, with both men and women after an early and short-lived marriage. But her most passionate and lasting relationships were with women. Although at various periods in her life, urged by friends such as Dorothy Oehlrichs, she considered marriage, she could not bring herself to sacrifice her independence and what she described in her diary as Strange wild wishes never quite the same. Desires no mortal man can name.

The result was that although most of Parsons’s artists and her closest friends knew about the women she loved, this legendary art dealer did not permit her sexuality to become a part of her public persona, the Parsons she presented to visitors to her gallery. In effect, she “passed” as heterosexual. What part may her sexuality, in whatever degree closeted, have played in the way she chose the artists she so successfully showed?

It is worth noting that the stylistic variation that Parsons cultivated in her gallery appeared also within the production of some of her individual artists: not only Sterne but also Sekula, who wrote to Parsons in 1957, “I paint each hour differently, no line to pursue no special stroke to be recognized by, it is still me though it contains over 1,000 different ways.” In the light of Parsons’s personal and business decisions, the refusal to grant one stylistic mode hierarchy over another begins to appear as something of principle. Never one to lock herself into something as fixed as principle however, she later said simply of her decision to reject the Giants’ offer: I always liked variety.