Roni Horn is an American multi-media artist whose books, photographs, sculptures and drawings speak on the mutability of self and of art in relation to nature. Her frequently haunting works insist that one’s sense of self is always marked by a place in the “here-and-there” and by time in the “now-and-then.” She describes her artworks as “site-dependent,” expanding upon the idea of site-specificity associated with minimalism. Widely recognized as one of the best conceptual artists of her generation, Horn has spent the last 30 years visiting the isolated geographies of Iceland, her enduring muse, as a source for inspiration.

In this excerpt from a 1994 interview with Jan Howard from Phaidon's Roni Horn, the artist eloquently explains how Iceland has come to have such a vital impact on her work, the importance of books, and what it's like living alone in a lighthouse for two months.

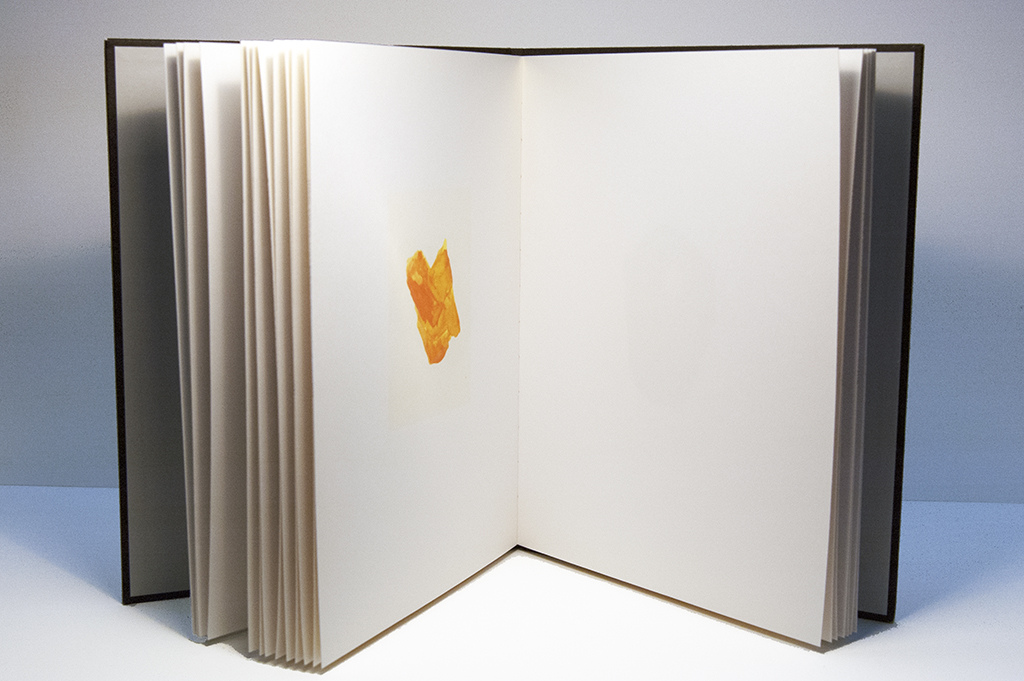

from 'Becoming a Landscape' (1999-2001)

from 'Becoming a Landscape' (1999-2001)

How did you choose Iceland, and how has it come to be so central to who you are?

Iceland could have been anywhere. But as it turns out, Iceland suited my needs. In fact, it seemed to form a perfect complement to my native home, New York. Iceland is the place where I have the clearest view of myself and my relationship to the world. By clearest view, I mean a view that is less constricted by social conventions.

You once commented that since you were in Iceland you no longer understand place as a noun, that the word now only makes sense as a verb.

Iceland is primarily young geology. Young geology is very unstable. In a literal sense, Iceland is not a very stable place. Iceland is always becoming what it will be, and what it will be is not a fixed thing either. So here is Iceland: an act, not an object, a verb, never a noun. Iceland taught me that each place is a unique location of change. No place is a fixed or concluded thing. So I have discarded the noun form of place as meaningless.

The verb, to place, as an activity in itself is a condition of being present. In the context of To Place, the verb operates dialectically. The view is not separate from the viewer: Iceland viewed is something other than Iceland. Similarly, the identity of the viewer is not separate from the place viewed.

In To Place, the viewer is me and the view is Iceland. This reciprocity is key to this body of work. Each volume is a dialogue spun directly out of this interchange.

spread from 'To Place Bluff Life' (1990)

spread from 'To Place Bluff Life' (1990)

What is your interest in the book form?

First, the book is a unique manner of address. Of great importance is the fact that the book is an intimate form; it mostly engages the individual individually. I can think of no other form so inherently private.

Second, the individual must be active in the exchange, not simply encountering or locating a given book but consuming it. In this sense the book chooses its audience. It was a circumscribed appeal.

Third, reading or looking at a book offers a peculiar analogue both to lived experience and to the experience of landscape: sequential relations, mostly cumulative and irreversible, order them.

Fourth, and for me of special importance: a book is not a simple object: within its particular identity it harbors the path of its assimilation into society. The book is distributed. As a mass-produced portable object that is financially accessible, the book goes out into the world, ultimately locating itself where it is most desired.

Fifth—and very close to this idea of distribution—is the ubiquity and reach of a book. Its portable nature allows the book practical, physical transit to virtually any place in the world. So although the book may wind up where it is most desired, there are no limits to the location of that desire.

Your first book, Bluff Life, records drawings made in Dyrhòlaey. Your trips to Iceland usually involve traveling around the country. Why did you decide to stay in Dyrhòlaey and live in its lighthouse for two months?

At the time I decided to stay at Dyrhòlaey I had travelled extensively around the country for years and I had visited this particular lighthouse on a number of occasions. The lighthouse was originally designed for a full-time keeper, though it was subsequently automated. So I knew there were basic living accommodations, that there was a room with a view overlooking the bluff, and, since it was in an isolated, sparsely inhabited area, I could be quite alone.

I wanted to go to a distant and solitary place and be there. I didn’t set out to accomplish anything. I wanted to be in this place, with not much to do and not much going on. I knew that whatever came out of it would be about who I was and about what this place was. I thought of it as a bluff life because I was literally living on a bluff and because I was wagering that I could find intimacy in this isolated, pared-down way of life.

drawings from 'To Place Bluff Life' (1990)

drawings from 'To Place Bluff Life' (1990)

How do the Bluff Life drawings relate specifically to Dyrhòlaey?

The Bluff Life drawings came out of Dyrhòlaey but I am not sure how they relate to it. I am sure that they are a result of being at Dyrhòlaey and nowhere else. Another place would have elicited a different body of work. Dyhòlaey’s influence is very particular, like every place.

Clearly there’s no attempt to depict the bluff. The drawings are a matter of the myriad and unaccountable influences of just being in a place. Perhaps it’s a form of memory.

So was drawing part of your routine while you were staying at the lighthouse?

I did many small drawings. It was very casual. I got up usually late in the morning and went walking along the cliffs. I spent a lot of time watching the birds since there were enormous populations of many species. I spent long hours lying along the grassier nooks or nestled into rock niches, watching the sky and water. It rained a lot and I read and drew in the lighthouse. At night and through most of the early morning until two or three I walked along the cliffs, keeping track of the incredible night life there. Another cycle of bird life plays itself out in the late night. It may be obvious already, but it was an extremely quiet time. In the book Bluff Life I use the phrase: ‘Letting the sea lie before me.’ I wanted to get to the point of no expectations, the point where I could be up there on the bluff in a kind of conscious passivity. This ‘letting’ is coming as close as possible to being present without influencing the course of a place or thing, without influencing the existence of something, while still being fully cognizant. I was keying my life to an awareness of the place. I really did get to the point where I could see birds intercepting other birds in flight and, although it may not have been grain by grain, I had a keen sense of the beach sands leveling.

Thicket No.1 (1990)

Thicket No.1 (1990)

I know as early as 1984 you incorporated text in some of your drawings. But you first used text in your sculpture at the time you published Bluff Life. The sculpture Thicket No. 1 (1989-90) incorporates the same Simone Weil quotation from her Gravity and Grace that you use on the back cover’s endpaper in Bluff Life: ‘To see a landscape as it is when I’m not there.’ How does the text function in these works?

In Bluff Life I use the quote to situate the work. Both the book and the drawings are introduced out of my desire to be present and to be a part of a place without changing it, even as my mind knows that such a desire can only be thwarted. Perhaps Bluff Life tries to describe some of what this place is without the viewer’s presence. But then, it’s obvious that someone made these drawings. These drawings are the seeing of a place.

In Thicket No. 1 the Weil text is part of the landscape, in this case a slab of unfinished, straight-from-the-mill aluminum, with an articulation partially visible on the far side, in another material. This articulation is situated so as to be present only as something different or enigmatic from the initial viewpoint. When the viewer walks around the piece the articulation reveals itself as text. It says in effect, ‘what you saw before you walked around to this side was’ - in this instance - ‘a landscape as it is when you are not there.’ The moment that you become conscious of your separateness from a place, contradiction arises. Thicket No. 1 gives the viewer an inkling of not being present. The contradiction lies in the instinctive weighing of that inkling against the reality, the certainty, of one’s physical presence in that same moment.