Italian conceptual artist Maurizio Cattelan is often described as a satirist, an art scene smart-ass. Known mostly for his sculptures, his tongue-in-cheek works also include photography and performance, all of which hit like visual one liners—provocative jokes that blur our perceptions of truth and reality. In 2010, for example, the artist installed a sculpture titled L.O.V.E. (a reference to the iconic 5th Ave. pop art piece by Robert Indiana ) in the Piazza Affari in Milan. It's a giant hand, carved in Roman Classical tradition, out of white carrara marble and sitting on a high pedestal. Like so many classical sculptures of hands however, there are some fingers missing. The only finger that has happened to survive this fictional art history is the middle finger, raised unabashed in a rude gesture for all the world to see.

Rising to fame in the 1990s, Cattelan is recognized as one of Italy's best known contemporary artists, receiving a major retrospective in 2011 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum that spanned the artists career since 1989. The artist is also the cofounder (along with photographer Pierpaolo Ferrari) of the bi-annual surrealist photo magazine, Toiletpaper.

In this excerpt from Phaidon's

Maurizio Cattelan

monograph published in 2000, the artist speaks coyly with then Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum director and critic Nancy Spector about his reluctance to take responsibility for his own work. Notorious for being a 'slippery' interviewee (he's been known to take answers from other artist interviews as an evasion tactic), Spector confronts Cattelan directly, revealing an artist who presents himself more as an unwitting jester rather than an artist.

L.O.V.E. (2010)

L.O.V.E. (2010)

Maurizio , I sense a certain reluctance about being interviewed.

My issue is not with the principle of the interview. Rather, I don't think I have anything interesting to say. When I read other interviews, there are always parts that strike me, and I ask myself, ‘Why don’t I just take this section since it’s so interesting? I certainly can’t do any better on my own.’ The idea then is to reorganize something already there, re-present something that already exists. I'd be happy to do this now. We just have to think about which interviews we like and which ones we can use.

I find it strange then that you asked me to interview you for your monograph if it were going to be a cut-and-paste operation. I know that the artist’s interview is a fundamental component of this book series so the editors must have discussed this process with you. What were you thinking inititially?

Well, they reviewed a list of names with me and I selected yours, since your office is close to my apartment. It’s a matter of convenience.

I’m going to ignore that remark. Does this mean that earlier published interviews with you are borrowed from other sources, pilfered from other artists? For instance, what about the interview conducted by Giacinto Di Pietrantonio in which you discuss your education in Paris? Does this mean that you never studied film theory with Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, Jean Françious Lyotard and Gilles Deleuze, as you claimed? I did think your chronology was a bit suspect. If we do decide to proceed with this strategy, I have to admit that I’ll be concerned. I’m liable for the truth of my statements as well as yours.

But, you see, the truth is not out there. It’s just the moment that you claim something as your own. This is my truth; that is yours. Besides, if we use other materials, you will still have the opportunity to observe how I work, and I will have the opportunity to learn more about other people.

Are there other artists whose work intrigues you enough that you want to adopt it as your own?

The problem with that question is that I am not an artist. I really don’t consider myself an artist. I make art, but it’s a job. I fell into this by chance. Someone once told me that it was a very profitable profession, that you could travel a lot and meet a lot of girls. But all of this is false; there is no money, no travel, no girls. Only work. I don’t really mind it, however. In fact, I can’t imagine any other option. There is, at least, a certain amount of respect. This is one profession in which I can be a little bit stupid, and people will say, ‘Oh, you are so stupid; thank you, thank you for being so stupid.’

What you are describing is a classic characteristic of the clown, the court jester who entertains through calculated buffoonery. Your self-derision or exaggerated humility, whether ironic or not, aligns your project with a tradition of clowning which has particular resonance in Italian culture, with its emphasis on the fine line between tragedy and comedy. The curator Laura Hoptman has placed your work in a trajectory that includes commedia dell’arte , Pirandello, Dario Fo and Roberto Benigni. To that I would add the character of Auguste from Federico Fellini’s film The Clowns , the quintessential underachiever and self-styled hack with a painted smile and real tears.

The tears are very real. Sometimes I don’t feel comfortable with myself. I think that maybe I don’t know myself very well but then I realize that I know myself all too well. Problems can seem very dark and the solutions are very far away. Sometimes I feel that I have to take a break from my life, a break from being me. That’s when I go to the movies, where I don’t have to think about things. It gives me eighty-eight minutes to escape from myself, whether I’m laughing or crying.

Does this stem from your relationship to your art?

No, the work sustains me. When I come up with something, the work is extremely exciting for me for at least two or three months. Such a joy!

So what’s making you happy now?

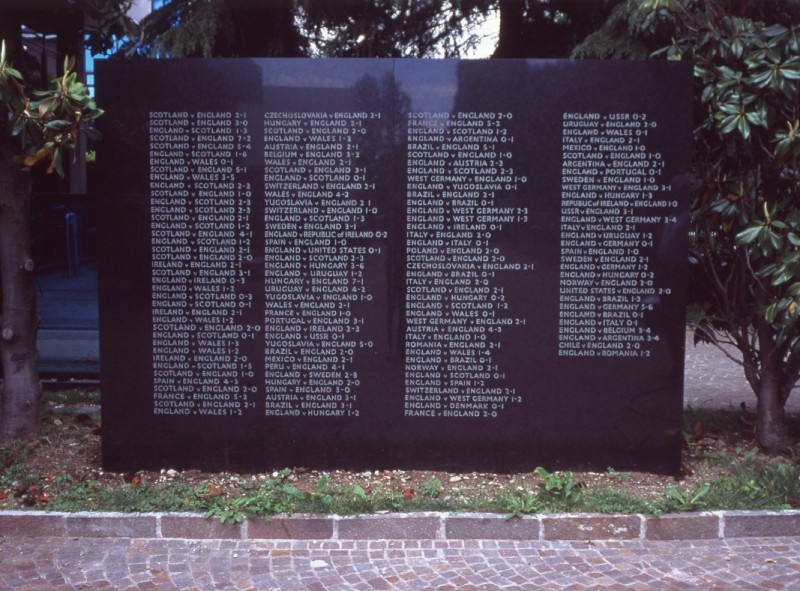

A fakir and a football team. For Harald Szeeman’s Venice Biennale (1999), I'm planning to show a fakir—a mystic capable of unbelievable acts of endurance. He will be buried in the ground with only his hands showing in a gesture of prayer or meditation. And for my show in London at Anthony d’Offay Gallery (1999), I created a big untitled granite plaque, similar to the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, DC. Carved into it are all the defeats of England’s national football team. I guess it’s a piece which talks about pride, missed opportunities and death, in a certain way.

Untitled (1999)

Untitled (1999)

The memorial reference could also relate to the fact that there has been so much violence associated with the game in Britian.

And also the violence that will be associated with this show!

Are you expecting the audience to be upset by your monument to failure?

Generally I try not to expect anything. But I’m afriad some people will get upset. First because I’m Italian; second, because football is one of the two or three subjects that you can’t touch; and, last but not least, because they think it’s a stupid idea. People want artists to come up with brilliant ideas, and the wall is not that brilliant. It’s a monument to my failure as well.

With both the fakir and the football memorial you are treading on sacred territory.

Not really. It’s like pointing a gun at an ambulance or insulting your own mother. It’s considered outrageous, but it seems like everyone does such things once in a while.

Your work is highly context-specific, in that it speaks directly to a particular culture in a particular time and space. Or, to use a militaristic metaphor, it is like a missile aimed at the heart of a specific cultural practice or belief.

Not necessarily. I really just take advantage of the exhibition situation. Because I don’t have a studio, I use shows as a means to get produced. Every commitment to exhibit becomes a challenge for me. If I don’t have any commitments, I don’t do anything. In some ways I’m lazy. I use my head only if I really have to. My creative process, as they say, usually starts with a phone call. I call a gallery, ask for an exhibition date, and only then do I start thinking of a project. I send the description to the gallerist. He or she phones back, we discuss it a bit. After all this, I start looking for people to produce the work. I never touch the work myself; it’s out of my hands. Of course, I would prefer to have a kind of unmediated representation, but this is not possible, given my process. The meaning of the work is really out of my control. I prefer to borrow someone else’s interpretation. After all, you shouldn’t be interviewing me. You could ask different people to come up with an interpretation of my work. They would know better.

That would be one approach, but it avoids any culpability for the work on your part. However, it is helpful to think of the objects and actions that you put out into the world as narrative devices, as triggers for stories that might differ from viewer to viewer.

Yes, this is more interesting, maybe. I like all the little stories behind the work. They make it more alive, I like faces and legends more than I like artworks. In 1998 I did a project on the campus of the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, for its Institute of Visual Arts. The project engendered a long story, almost a novel. When I arrived there, first I wanted to show a series of films. I wanted to steal these films from the cinema at the university. But something went wrong with the equipment so I had to come up with a new idea in a couple of days. I decided to build a sculpture out of rags and old clothes; it was an effigy of a homeless man—Kenneth (1998). I left the poor guy near one of the campus buildings. The next morning it turns out that someone had stuck a sign on my sculpture, complaining about the tuition increase at the university. The homeless had become a kind of symbol in a struggle I knew nothing about.

After that, neighbors started to complain about my piece, until eventually someone stole the sculpture, leaving only its shoes. So the police took over the situation; there were officers looking for a missing sculpture. A perfect plot, isn’t it? The police found two different sculptures and neither of them were mine. The next day a new sculpture pops up, carrying a sign saying something like, ‘We don’t need an Italian to teach us what art is.’

Actually when I first made this piece, in Italy—Andreas e Mattia (1996)—I recieved some really different reactions. It was another story but with the same cast of characters: a policeman, some neighbors, a homeless man. Some people were upset and called the police to complain that no one was taking care of this poor, old person on the street. So they went to check on his condition and started shaking him, saying, ‘Hey, hey, wake up. It’s time to go.’ And when he didn’t move, they thought, ‘My god, he’s dead.’

At times I like the idea of taking these stories a step further and creating a sequel. I have actually been thinking about a work I could do in Buenos Aires which would involve installing ten to twenty fake beggars around the city in the early morning and then gathering them at the end of the day in order to collect the money they recieved.

Kenneth (1998)

Kenneth (1998)

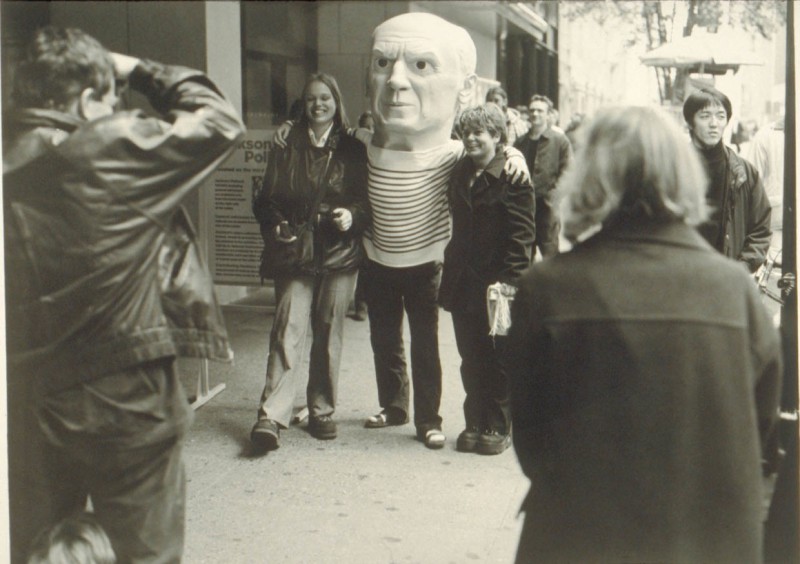

Your work provokes such stories to unfold. While you claim that your art is not necessarily context-specific, I would say that it addresses certain situations by intervening and becoming a deliberatly provocative presence, an irritant that refocuses one’s perception. How else would you describe the fun-house version of Georgia O’Keeffe (Georgia on My Mind, 1997)—complete with bulbous head and exaggerated features—which attended the opening of the second SITE Santa Fe, just blocks away from the new museum devoted to her work? Or the masked character of Pablo Picasso (Untitled, 1998), doyen of high Modernism that he is, greeting visitors to The Museum of Modern Art like a mascot for some theme park or sports arena?

Oh my god, no, no. I don’t think so. I don’t think of the work as intentionally provocative. What other works do you consider provocative?

What about the time you had your gallerist Emmanuel Perrotin wear a giant rabbit costume that doubled as an immense, flesh-colored phallus for the duration of your exhibition in 1995-a work that you called punningly Errotin, le vrai lapin , meaning ‘Errotin, a true rabbit’? Tell me you weren’t poking fun at the artist/dealer relationship or critiquing the erotic cycle of distribution and consumption that is inherent to the gallery system.

Acutally, I think that piece lacks any provocation; it has a zero degree of subversiveness. It’s just a comment on the private life of this dealer. It was a game played between two people; that’s all. It was fantastic because he was willing to go along with it; he laughed with me. It is very well known in Paris that he is a perpetual womanizer. So nobody thought for a second that it was a provocation. It was nice of him to allow himself to be presented in this ironic manner. However, I guess if you saw the performance from the outside, it could seem provocative. The viewer might feel that he or she is being treated like an arsehole or that the gallery is a place where some kind of bizarre theater takes place. There is always this tension in my work, between my intentions and reality, between what I wanted and what people end up thinking.

Untitled (1998)

Untitled (1998)

In terms of the Picasso piece at MoMA, I felt that there was simply something missing at the museum. I didn’t understand why they didn’t embrace a more visible means of marketing and promotion. They shouldn’t be ashamed. I think it’s something that we will be seeing more of in years to come. What does it mean to be a cultural institution? Don’t they want more visitors or do they just want to be boring? In any case, they are already selling coffee mugs, T-shirts, calendars and posters. I don’t think it’s such a sin. The Picasso figure was very popular; lots of people were taking pictures of themselves with him, as in the photos you take standing next to Disneyland characters like Mickey Mouse. It shows that people always want a different kind of memory of this place, a more personal memory. If the Picasso figure did anything, it was to promote the museum as a friendly place. Georgia on My Mind was a much smaller gesture, a rehearsal in a way. I don’t usually repeat the same work twice, but the situation called for it. However, this work wasn’t perfect. The head was made in the carnival tradition and it was meant to be playful, but in Santa Fe the figure became a ghost.

Wasn’t your contribution to Sonsbeek 93 in the Netherlands rejected because the work was considered to incendiary?

That’s true. But again, the intention was not to irritate. For this exhibition, I proposed using the entire city as a chemical experiment about fear. I had gone to Amsterdam on my way to Sonsbeek and while there I had casually eaten some cake, without knowing that it had been laced with some drug. For one day I was completely out of it. The experience was so surreal and intense that I thought afterwards, ‘Yes, this is what I want to do for the Sonsbeek exhibition.’ I wanted to alter people’s perception of the city in this total, all-encompassing way. But at first I didn’t know how I could accomplish this without using a drug, without lacing a cake for all to eat. Them I realized I could cover the entire city with a poster campaign and decided to use one that advertised an underground meeting of neo-Nazi skinheads during the week of the opening. I thought this was perfect because the neo-Nazi reference would create a fiction of a fiction, as long as nobody knew that it wasn’t for real. I had this kind of experience in Amsterdam and thought it would be interesting to emulate it in some way for a large number of people.

The opening of the show was scheduled to include a visit from the Queen, so there was already a massive police presence, which might have made the whole thing more believable, more hallucinatory. So everything was perfect. But the curator didn’t like the idea of neo-Nazis. She thought it was too strong a comment about the Second World War and about the atrocities that they hadn’t experienced there directly. She said that I had no right to use those symbols. I was too presumptuous. In a way, she was right. But in another way, it was an overreaction. Nevertheless, they kicked me out.

You must have been aware of the political implications of invoking neo-Nazism and, by extension, the Holocaust, in such a context even if you were, as you claim, just trying to create an altered reality. Even the most sincere attempts to mine the Nazi past through humour are met with scepticism and anger. Think of the recent objections to Roberto Benigni’s Holocaust film, La vita é bella (Life is Beautiful, 1997) on the grounds that such subject matter cannot be treated lightly. I am citing this example in particular because you are often compared to Benigni, Italian satirist that you are.

I’m not really sure satire is the key to my work. Comedians manipulate and make fun of reality, whereas I actually think that reality is far more provocative than my art. You should walk on the street and see real beggars, not my fake ones. You should witness a real skinhead rally. I just take it; I’m always borrowing pieces - crumbs really - of everyday reality. If you think my work is very provocative, it means that reality is extremely provocative, and we just don’t react to it. Maybe we no longer pay attention to the way we live in the world. We are increasingly… how do you say, ‘don’t feel any pain?’ … we are anaesthetized.