Raymond Pettibon’s current retrospective at the New Museum, “A Pen of All Work,” is the 59 year-old artist’s first major survey, despite having become an established artist since the mainstreaming of punk. With roots in the self-published zine culture, Pettibon first gained recognition designing album covers for California rockers Black Flag, before distancing himself somewhat from such anti-establishment associations. Since the '70s, Pettibon’s work has combined a scribe’s love of language with a draftsman’s hand, yielding not-infrequent comparisons to the poet-lithographer William Blake. The heretical reputation is earned from paintings that juxtapose pithy quotes and the likes of Charles Manson, Bible verses next to surfers. In interview excerpted from Phaidon’s brand new monograph, Raymond Pettibon: A Pen of All Work, Pettibon speaks with Massimiliano Gioni, the curator of the New Museum’s current retrospective. The two touch on the self-published zines, narrative content, and the role of literature visual motifs in Pettibon’s work.

When would you say that you knew you were going to be an artist? I think it is a relevant question particularly because we are including some of your childhood drawings in this exhibition.

I would say when I was 18 or so. I was studying economics, and I had already been quite disengaged from that as far as vocation goes. And I was no longer interested in teaching and so forth. My earliest work, discounting the drawings I did as a child, I think can be dated to my late teens, when my vocabulary took shape and form as a dialogue or a struggle between words and images—pretty much what I continue to do.

I know it is never a planned, clear-cut choice, but did you decide at one point that you would be working mostly in drawing or, more broadly, that you would be making or consciously engaging with the tradition of cartoons, comics, and illustrations?

I never made illustrations. I did some political cartoons early on, and that comes down to the relationship between the word and the image more than anything else. But to me it was apparent that the difference between my art and political cartoons was that my work is not so direct after all. It’s not made to make a point: It’s not a caption in a book. It is much more open-ended.

Were you reacting against other artists at that moment? Or were there artists who formed your pantheon, so to speak—who you felt were working with you or somehow giving you permission to do what you were doing?

There were certainly precedents I was aware of, like Goya and Daumier, for example. In a sense, what I was doing was not a completely original departure from everything else: It was part of a tradition. And, closer in time to now, I remember I was interested in the photographer Duane Michals, and later I met Mike Kelley.

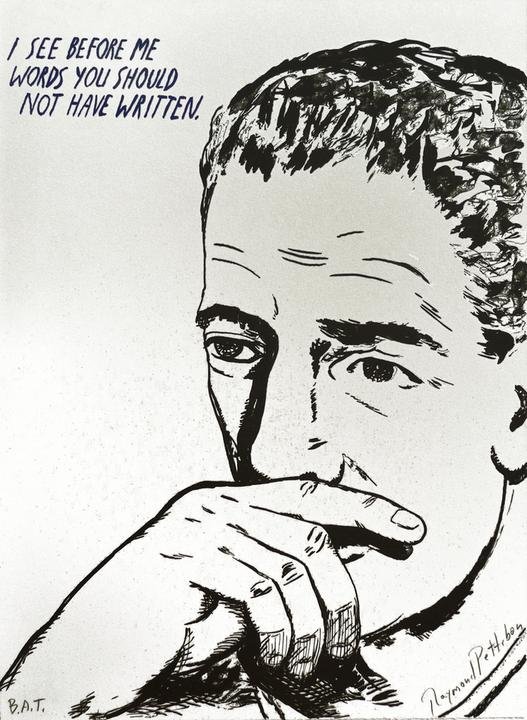

Raymond Pettibon, No Title (The Way She) (2006)

Raymond Pettibon, No Title (The Way She) (2006)

A lot has been said about you being a quintessential Californian artist. At the time, was there an artist within the tradition of Californian art that you felt closer to? Obviously one cannot avoid thinking of Ed Ruscha in relation to your work: even though you are extremely different, you both have turned words into objects and pictures.

Yes, of course, I loved Ruscha and, more generally, I knew the Conceptual art of the time. And I was very interested in Minimalism even. I used to have piles of Artforum and other magazines from the ’60s and ’70s. So I was aware of what was going on. You see, I’m not some outlier or outsider. I know it is not what people want to hear, but it’s not that my approach was coming out of some pure, isolated sensibility, like that of outsider artists or of comic-books nerds. I think that’s a myth.

Did you feel part of a community with other artists at that time?

Not really. There weren’t many people who were doing what I was doing. So no, I was not part of a group or a community, not in a social sense at least.

I want to go back to what you were saying about the difference between political cartoons and your work. I understand you don’t think of your work as an immediate commentary, but one can always sense in your work that you want to intervene on reality or, more generally, you want to engage with the world. Perhaps it’s just the insertion of text, which makes the work more deictic, like it was directly pointing toward reality. Standing in front of your drawings, I never have a sense that they are just pictures to be looked at: they are always transitive, in a sense; they are charged with a sense of urgency. It is as though they were constructed to change my view of the world. Maybe this is simply a type of attitude your work shares with the tradition of social commentary that someone like Daumier was part of.

Yes, but I think in Daumier’s case, he did have a measure of power in affecting things. In my case, I never had grand ambitions that such a thing was possible in my work. So if I were capable of intervening, if I were the President of the United States, then okay, I would take that responsibility—but I don’t think being an artist in this day and age has any position of power as a platform. If anything, that would be negative: people would outright oppose your position... Whatever cause you’re working for, you’d be doing it a disservice because the role of the artist, as it has been shaped at this point in time, doesn’t allow for that type of engagement.

Speaking of engagement, quite early on in your work, you started making fanzines: Captive Chains was the first one and was published in 1978. One could read this not only as a very personal and experimental distribution network, but almost as though you were setting up your own media system. Benjamin Buchloh has said that, through the sheer quantity of your own work, you have unleashed a kind of artisanal media network, a handmade assault on mainstream media. The very choice of the format of the fanzine seems to be a strategic decision: it’s a way to be very much engaged with the state of the world, to disseminate your own work into the world.

But the fanzines were utterly a failure, though. Of Captive Chains, I think I sold one copy.

How did the distribution work, or, better, how didn’t it work?

There was an advertisement in a punk magazine, and that was pretty much it. But you can’t really speak of distribution or of marketing: there was nothing like that. At the most, for each fanzine there were five hundred copies, and sometimes quite less. And now I think the average amount of extant copies is much smaller because at one point I destroyed most of them so they wouldn’t clutter up my place. They became collectible at a later date. Personally, I wasn’t playing hard to get or looking to make things scarce or to make a collectible out of them. On the contrary, I wanted the fanzines to be read, but nobody seemed to care for quite some time.

Did you want more people to see your work?

Sure, that’s still the point today. On the other hand, I can’t concern myself with that sort of thing. That’s what you have galleries, publishers, and museums for. As an economist, I would make a terrible businessman or marketer. The point of my studies was not to delve into the business world. And in general, as soon as I finish the work, I don’t want to think about it. It either finds a place in the world or it doesn’t. In my case, it eventually did to a degree, but that wasn’t by maneuverings or back-handed deals or marketing strategies or anything like that.

But when you were working on Captive Chains, had you thought of it as a complete cycle? You knew right from the start that it would exist as a fanzine.

Yes and no: there wasn’t a lot of forethought involved. And if there was, that became a crashing failure. I didn’t have set goals or ambitions for where any of this would land. I never went out to the art world and knocked on doors with portfolios either. For the longest time, there wasn’t a market for or even an interest in what I was doing. There wasn’t a business model either. I guess it was by the force of the work that eventually people started showing it and caring about it. I am asked often by young artists and whomever about how I did it or made it. I wish I had something to tell them, but usually my advice is to say, “just don’t do what I did,” because my path isn’t really a model of success. And the underlying assumption is that people think that there is some kind of secret, that you have to be part of the illuminati or know the secret handshakes, or you have to suck cock, to be crude. And of course there is no such thing as a secret, and all this paranoia takes everything away from the work itself. If it’s a great work, you will get attention for it eventually. Nowadays it’s actually probably much more difficult not to be noticed. It’s hard to hide even if you want to.

Were you reading other fanzines at the time? How did you come to the choice of that medium? Were there other fanzines that you cared about, by comic artists perhaps?

In comics, yes, they have a long tradition of fanzine. That’s probably where it started. But you could say Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman is a fanzine in a way. Self-publishing has been around forever. Proust self-published. Although I seemed to borrow my style visually from comics, I wasn’t part of the comic-book world. I guess the closest would be punk fanzines that were around at that time, but then the bridge between art and music is not really accommodating, and it runs only in one direction. I never had any real support from punk rockers or music. That’s all way, way after the fact.

Were you thinking of your fanzines as complete narratives? In Captive Chains, I love how the story slowly disappears and the work becomes progressively more visual.

Well, there is one story in Captive Chains, and narrative was important for me. At the time I wanted to do something in the style of James T. Farrell, who did “Studs Lonigan” in the style of teenage New York gang novels. You know how great filmmakers find ways to reference other filmmakers without burdening their work with quotations? I was trying to do a lot of that in Captive Chains. So, for example, you can find all these visual-art influences, especially Reginald Marsh, Edward Hopper, John Sloan, and also a fair amount of film-making references. I make films—or videos, if you want to be technical about it—so that has lot to do with my work: the film image and the dialogue, or the silent film where you had the subtitles, all these are things I thought a lot about in relation to my work. So even if there is one single drawing, it still can be very much about narratives. If we take a still out of a motion picture, whether you have seen the whole movie or not, that single picture retains a narrative element; it’s a snapshot taken out of time—it has a past, a future, as well as a present.

That quality is perhaps one of the defining traits of your work. Even in your most pictorial pieces, as a viewer you always have the sense that you are witnessing something that is either part of a larger narrative or that is happening at a precise moment in a ow of events. The picture seems to capture the event in its climax or just before its occurrence, so it is always a still—frozen and enlarged, cut from a series of events. In Italian we say that someone is caught “in agrante,” meaning at the very moment in which the crime is consummated. That’s what your pictures always make me think of.

Yes, “in agrante delicto,” we say in legal jargon. But the great thing is that even the most precise, frozen image always remains open and ambiguous. If you look at the Zapruder film of Kennedy’s assassination—which is, I don’t know, how long? just a couple of minutes—so many narratives have been woven around those single images. How many books claiming to come to some conclusion about Kennedy’s assassination are there? I’m sure there are thousands. Every frame has been analyzed and interpreted in myriad ways. The same still happens today with every police shooting, for instance; depending on what side you are on, each still carries a completely different meaning and degree of truth. In sports, you have instant replay, and even that is always a matter of interpretation and can also be opened up to more misreading or ambiguity. My works don’t claim to have an absolute veracity, and that’s perhaps the biggest difference between political cartoons and my work. My work is not wrapped up in a punch line.

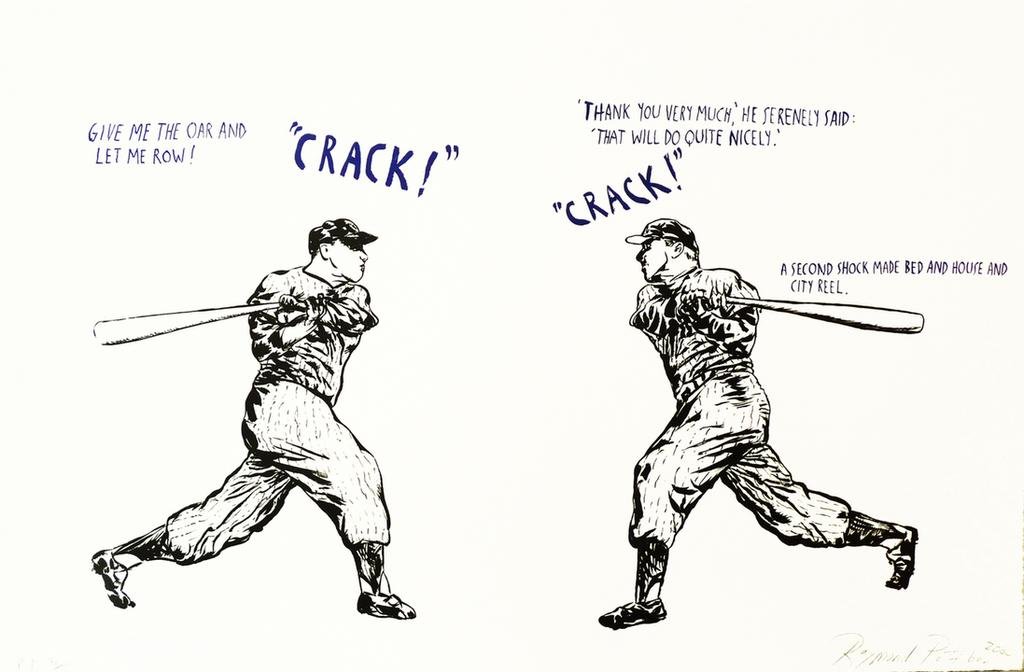

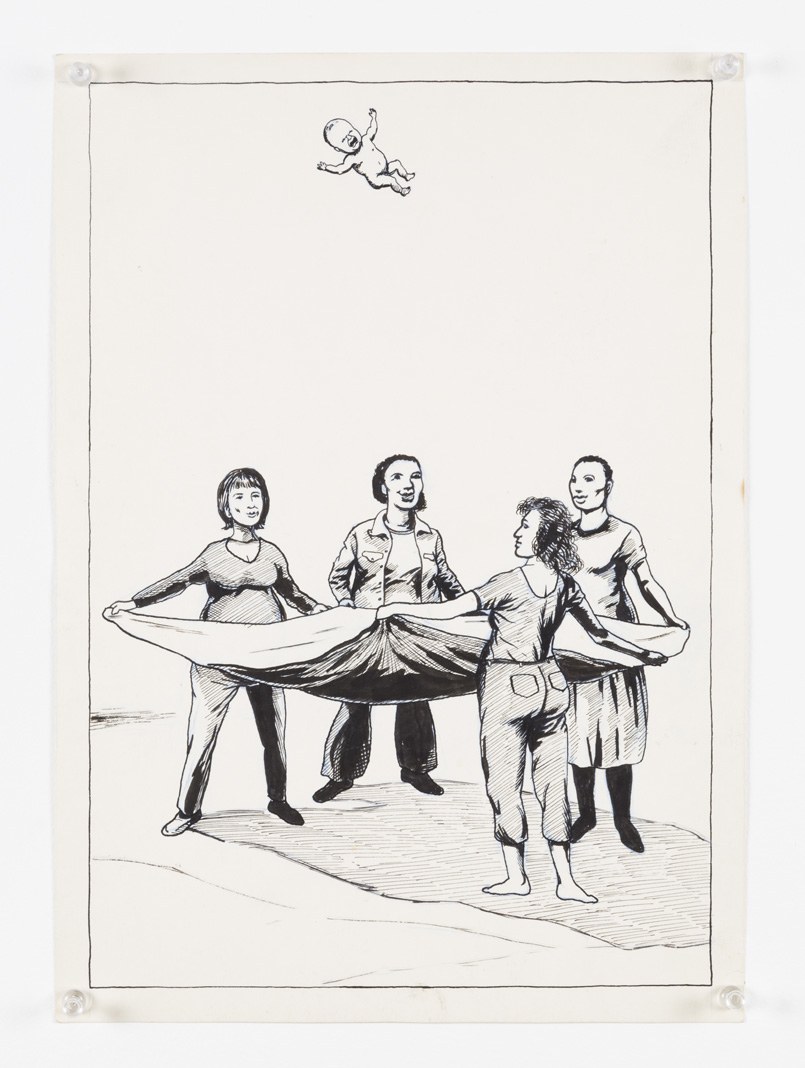

Raymond Pettibon, No Title (Baby Blanket Toss) (1981)

Raymond Pettibon, No Title (Baby Blanket Toss) (1981)

So in a way, as you make your drawings, you try to open up multiple readings of your work. That’s another specific quality of your work: it is direct but never mono-dimensional, which I think relates very clearly to the voices in your drawings. Who is really speaking in your drawings?

Sometimes there are several narrators within a single drawing. Sometimes I make that clear. And other times I can even go back to something twenty years later. You can tell by the handwriting, the color of the ink, or whether it’s cursive or not. That’s just something I assume that people know. In a way, the work is in a continuous dialogue with itself, back and forth. There isn’t one universal god of a speaker. The tablets don’t come from heaven. It is closer to William Epsom and his Seven Types of Ambiguity, which was very important to New Criticism. One of the ways of being ambiguous is by being apparently direct. You can be straightforward and still open things up to multiple readings. And you let the work, whether it’s a visual image or the writing, speak for itself.

Ultimately what I have to say about my own work doesn’t have any more access to the truth about my work than anyone else’s reading of it. Of course, I can try to say what I was thinking or doing when I was working on a specific drawing, but when I am working I am not thinking about where I stand. Working in a language, it’s not some grand overview. I am not looking over my shoulder as I work.

In a text about your work by artist Frances Stark, she brings up Harold Bloom and his book The Anxiety of Influence and proposes a sort of deconstructivist reading of your work: she suggests that your texts are always about other texts, in the way that each book is ultimately about all the other books that came before. So there is no omniscient author in your work, but there is a type of omniscient reader: the author that is inscribed in your work seems to have read all the books out there.

One of the revelations I had as we were working on this exhibition was getting to know better the process in which the language in your drawings is both cemented and produced over time. There are texts you have worked on literally for years, in some cases cutting out excerpts from books, which you then rewrite or correct or intervene on, and which eventually find their place in drawings many years later. There is something inherently polyphonic in your work, a multitude of voices and styles.

Yes, you could say I borrow quite a lot. I always did. However directly or indirectly. Or I guess it’s always indirect, because I transform all these different voices into what I do. I think that the concept of the anxiety of influence is very crude: it presumes an idea of influence and relation to other artists and writers that is almost competitive or Freudian, the kill-your-father thing... Most of my work does come from reading in one way or another. It can come from reading literature so closely that the overall narrative almost dissolves, but it can also come from just reading a restaurant menu or capturing the chatter from the table next to you.

Did you develop your ear for language through reading or through listening? There is always a gnomic quality to your texts, something definitive and final. Is that something you learned from literature?

Really it is just whatever works. But of course there are also some tricks of the trade, so to speak—for instance, the cut-up method, or just ways to start the flow of associations. Cartoonists do this. Stand-up comedians do this. Poets do this. I was never taught any of it systematically; I never studied it, but I have been using similar methods for years and only heard about other people using them much later. There are certain things you can do to improve your ear for language, and eventually I realized I’ve been doing this sort of thing for most of my life. Writers, public speakers, politicians, fortune-tellers, preachers, and faith healers, they all do it: they learn how to read their audience. Sometimes it’s pretty crass, other times it’s more refined.

Did you ever have a clear idea of who your audience is or should be? Again, borrowing from literary theory, we could use Umberto Eco’s notion of the model reader, that is the ideal reader that the text imagines and produces. Did you ever have such a thing as an ideal reader in mind?

Actually that’s something I always thought of. And, I should be clear, it wasn’t pitched at as a market. But, in the most basic terms, I know that the reader is not myself, it is a projection. “Ideal reader” is a good way to put it. Or we could speak of what Adam Smith called the impartial spectator, which is a way of saying that the reader inscribed in the work can be a moral compass or a conscience, like in cartoons, when they have the devil and the angel on either shoulder.

All this thinking though is very much internalized. It’s not like I imagine a model reader every time I make a new work. Actually for the longest time I didn’t have an actual audience at all. Maybe that’s why I had to develop an ideal reader, because there was no real audience. Interestingly enough I never had an editor or a publisher, so there was nobody forcing me to narrow down my work or make sense of it. I could never work with the constrictions of being a commercial artist, which allowed my work to be more amorphous. So the ideal reader, whoever that may be, is the one who will make you reach higher.

At a certain moment in time, a very specific type of audience became associated with your work: the whole punk, hardcore movement in Los Angeles and beyond. I am curious to know how you felt about that reception and whether you consciously addressed it in your own work, for example with your drawings about and against punks.

No punk ever bought or really cared about my work. And I am not trying to distance myself in any way. I did half a dozen album covers and I did some flyers because my brother was in Black Flag. I don’t harbor any resentment, but if people knew the circumstances, with SST and Black Flag and punk rock in general, I think they would have a very different perception of my work in relation to that movement. In 1989, I made a film called Sir Drone, which is about the punk rock scene in LA in 1977 and 1978. It was meant as a comedy, but it’s the closest thing to a documentary as has ever been done on that subject. I happened to be close to the punk movement, I guess you can say that, but did it really relate to my art? Was there any communication back and forth? I don’t think so. I was part of the punk thing, but not as an artist. I am not really interested in this kind of cheap historicity, which has ended up constructing a ction of myself as a punk author.

Because your work contains such a multiplicity of voices and references, I think that people can project different images on you as an author. They can imagine you as different characters, because there are all these different authors evoked by the many subjects who seem to be speaking in the first person in your drawings.

Not that I am drawing any comparison, but it’s the same thing that happens with Shakespeare: there are so many interpretations of who he was because he could master every voice.

As we have gone through literally thousands of your drawings, there is almost something vertiginous and sublime in the vastness of your range: it’s like you are speaking in tongues... Do you think your range has changed through time? Have you expanded your tonality?

I saw one of Marlowe’s plays a few years ago. And at one point I recognized the line that had given the title to my Captive Chains. You see, I didn’t even remember anymore where it had originally come from, but when I heard it, it brought me back to the time when I was working on it. The thing is that there is not so much of a personal stamp on my work. It’s not confessional: I am not speaking from the heart. If it is taken as a whole, perhaps you can see some kind of personality and sensibility. But I am not even sure about that. That’s not the point, anyway. I am not looking to put my personal stamp or my self-portrait on the world.

And yet in some cases—and I am thinking of your more recent work about and against the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—one could really think that it is you speaking through those drawings and that you are actively trying to intervene in the world and change people’s minds, quite frontally and directly.

If I could, I would, but I don’t have any delusions of grandeur on that part. It’s more about going on the record and, as lame as that might sound, it’s about saying, “Well, okay, I was right.” Or even just saying, “Well, I took a position.” And that’s pretty lame too, I know, so I hope it’s more complicated than that. But when I was working on those drawings, it seemed to me there was no other voice heard except a lot of flag-waving and blustering. So within this void of opinion, I just thought it was time to do something in politics, but I knew I wasn’t going to change hearts and minds and influence people or anything. And then when you actually read the texts or hear the voices in the drawings, it is clear that it is not simply me speaking through the work.

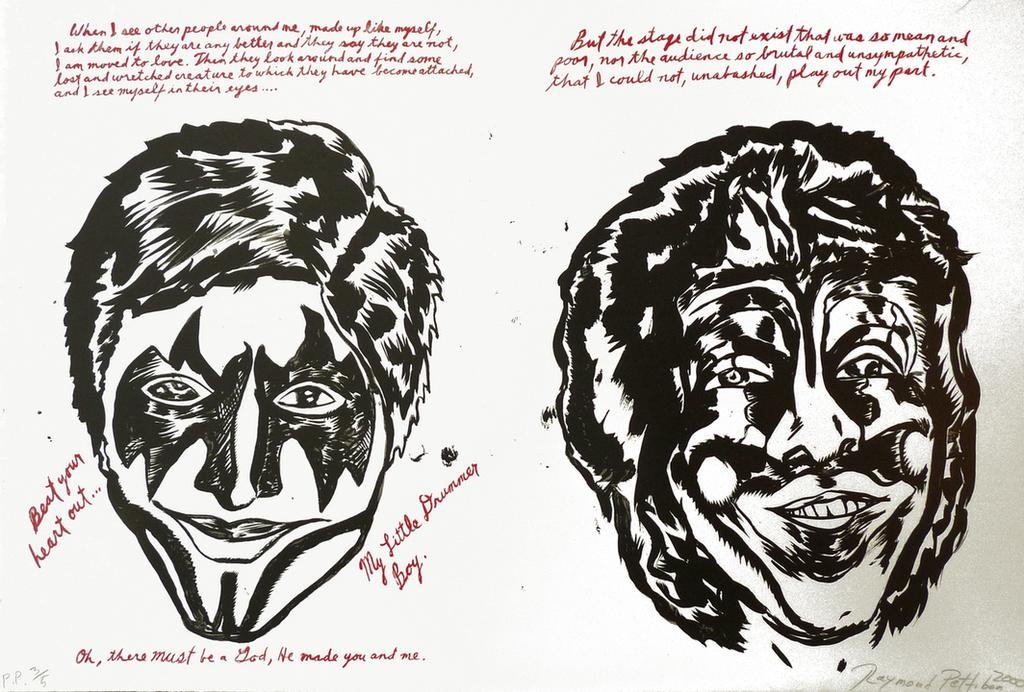

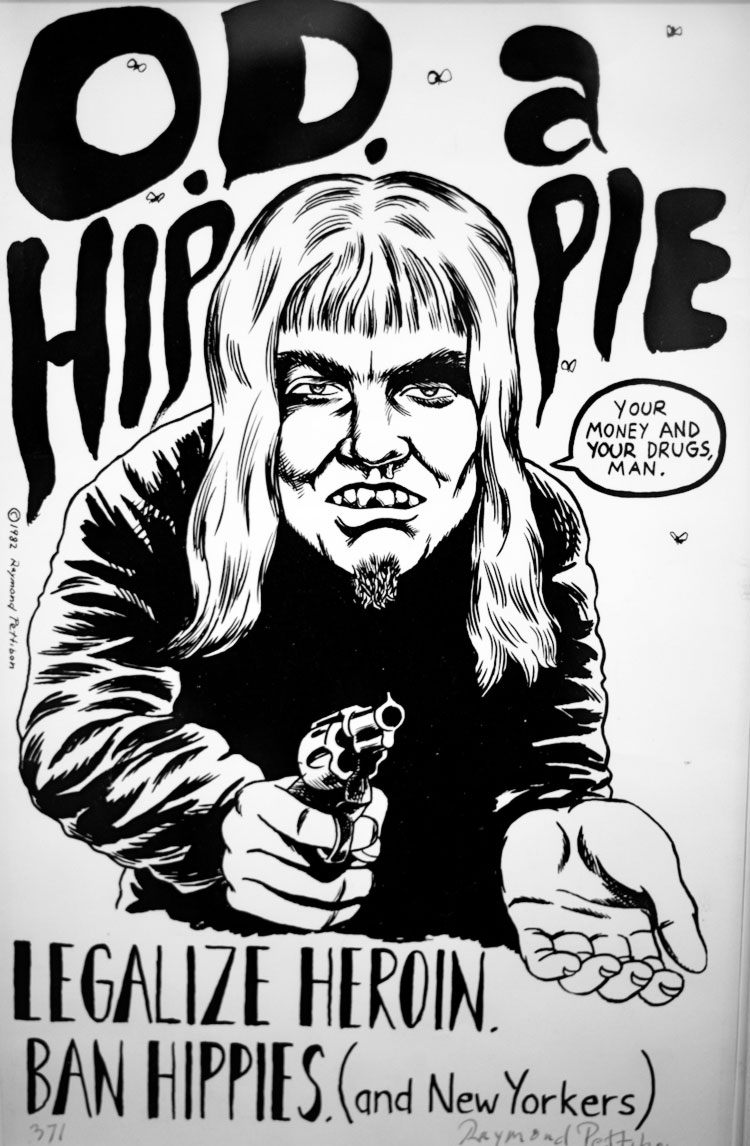

Raymond Pettibon, No Title (O.D. a Hippie) (1982)

Raymond Pettibon, No Title (O.D. a Hippie) (1982)

You have periodically used your work as a commentary on history.

Often I have done so after the fact; I wasn’t around when the hippies were there or when Manson and the Kennedys were there. The fact is that history just repeats itself, relentlessly, which is kind of depressing. So to put a stop on it for just one frame, isolating a still, as we were saying earlier, that lets you understand things better.

I have piles of drawings of the George W. Bush era, for example, which sometimes I have gone back to and put just Obama’s face over George W. Bush’s face and it says the same thing. I’d rather do other things than deal with presidents, but things repeat over and over again. I mean, we have the Clintons, the Trumps, and it will be Chelsea Clinton running in ten years. And she will be up against one of the Bushes or Obamas, whatever.

What you are saying about returning to certain drawings across time was another quite surprising revelation for me. I think many people have the impression that you just work very fast and very impulsively, producing thousands of drawings; it’s one of the many myths that surround you and your work. But I was surprised to learn how much more editing and revising and revisiting of your own work goes into your practice.

I could probably do fifty drawings a day. For what purpose I don’t know though. But I guess I could. Sometimes you have to do it, to get to a state of fluency, like those calligraphy masters who can execute a drawing in a few seconds, with such an economy of lines, simply because they put in fifty, sixty, seventy, eighty years of practice to get to that point. In actuality, I still don’t have that fluency. Each time it is really a struggle to start. I mess it up and start it over. I don’t make it easy on myself; sometimes it nearly borders on neurosis, even. People probably think I can just crank this stuff out, but I can’t.

Would you say there have been dramatic changes in your style throughout the years?

I don’t know about that. I think the consensus would be to the contrary, that I am doing the same thing over and over and over. To me personally it seems that the scale of growth is more evolutionary than based on dramatic changes. The first book I did had a relatively long narrative: it was more of a story. My relation to the narrative has never left me, but I have developed various ways of working it out. Collage can stop the flow of narration. It can be disjunctive. And the scale of the work itself, that has changed, but in a way it’s irrelevant because sometimes it’s a hell of a lot easier to work large than to work small. And I guess you can say my drawings on paper have become more painterly, for better or worse, but that changes every now and then.

More recently you have started using the exhibition itself as a medium. I am thinking of your pieces for the 2002 Documenta, or for the Venice Biennale in 2007, or the recent series of shows at David Zwirner, which often involved some form of wall painting, graffiti, or intervention on an environmental scale.

There can be practical and pragmatic solutions behind all these kinds of choices. For example, I did the very first wall drawings because I didn’t want the galleries to steal my work. You know, galleries like Zero One or Ace Gallery—I wanted to be careful. So in a way, the wall drawings really grew out of that initially.

But all of your wall paintings also feel more public. I am not sure if it is a stretch to evoke the tradition of muralism, but the wall drawings certainly feel more declamatory.

Yeah, that’s a good way to put it. But each time it’s different: it can be related to the place, the locale, the gallery, the museum, the circumstances. In the end, sometimes it's not what you are saying but how you say it that really matters. The language is on fire and you just spit it out.