At least since the days of Delacroix and Manet, painting has vacillated between figuration and abstraction, with attention sometimes given to the smears of paint and at other times to the object those smears depict. In the 20th century, with the advent of pure abstraction, the pendulum swing became much more pronounced: Ab-Ex was followed by Pop followed by Neo-Expressionism followed by the ‘90s figuration boom with John Currin, Elizabeth Peyton, Lisa Yuskavage, et al.

We now stand at the tail end of an abstraction-heavy moment—a period characterized largely by the so-called market-driven phenomenon of Zombie Formalism—with the figure being taken up with enthusiasm by painters as diverse as Jamian Juliano-Villani, Ed Fornieles, Matthew Watson, and many of the artists in MoMA PS1's current Greater New York survey.

It's an exciting time for painting, and it so happens that the return of figuration coincides with the release of Phaidon's new book Body of Art, an ambitious compendium of depictions of the body from across cultures and throughout time. To discuss the status of the figure in recent painting, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Contemporary Arts Museum Houston director Bill Arning about the visceral, sexy, irresistible allure of the body in art.

Click here to learn more about Phaidon's Body of Artand buy thebook.

The tensions between abstraction and figuration that formed the great battleground of early 20th-century painting seem to be in an interesting place right now. What’s going on?

Well, when you look at the early manifestos of abstraction, simply being non-figurative was among the highest values—if something was still at all discernibly based in visual reality, the feeling was that the artist wasn’t pure enough. And there were hierarchies of artists based on how well they adhered to this measure. Actually, I was just talking to the great Houston gallerist Fredericka Hunter about how, even before the days of the Internet, the information systems among artists about who was doing what in what part of the world were really effective, so they were able to keep score. Now, however, we live in such a hybrid time of figuration and abstraction that Cecily Brown or Marilyn Minter, who are the great figure painters of today, are always borrowing techniques, looks, feelings, and scale from abstraction.

By the looks of it, we are at the tail end of another abstraction-heavy period, where the decorator-friendly approach to process-driven abstraction known as Zombie Formalism is now wending into something more hybridized still. You can discern this easily at the indie art fairs like NADA—you’ll find booth after booth of figurative paintings. Why do you think that is?

I do think that Laura Hoptman’s Forever Now show at MoMA did codify a period, and as soon as those things get codified they kind of get closed down in terms of new artists entering. When shows like that are pulled together, what happens is that certain names dominate the playing field and then it’s a contest between those players about who will have the most staying power and vivacity, or who will still be exciting in the next few years. It was a strange show, too. It got such negative critical responses, but there were a lot of artists in it—like Matt Connors, Mary Weatherford, and Richard Aldrich—that I think are terrific. But if I was a young art student and I saw that show, I would say, “Okay, that ship has sailed. Where else can my work go now?”

And you think figuration is part of the answer there?

Yes, very much. I saw the “New Objectivity” exhibition of realist painting from the Weimar Republic this summer at the Museo Correr in Venice, and those Christian Schad paintings could totally rock through a Lower East Side gallery today. The only thing is, it would be a little bit less male-centric, since the Neue Sachlichkeit was generally an argument by men about other people’s bodies, and now feminism and new thinking about race and sexuality has fundamentally changed portraiture.

The other thing I’ve been thinking about from Venice is the Henri Rousseau show at the Palazzo Ducale. It was absolutely fascinating to see this guy who was not an outsider or a folk artist but who was immediately pegged that way by all of his contemporaries—so much so that when Picasso celebrated him at the end of his life, nobody was quite sure if he was making fun of him or not.

He also would look relevant in a Lower East Side gallery right now. Kind of like a proto-Jonas Wood. What is the appeal there?

One of the things that figurative art does is that it immediately questions the good-taste/bad-taste borderline, because figurative art has something illustrative about it by its nature. It’s going to deal with specificities, the smelliness, the flaws of the human body. So, while the book talks about the ancient ideal that everything perfect in the world is somehow expressed through the human body, that narrative is no longer available to us because today we think of bodies as things that need to be fixed. We all have to go to the gym or do yoga or change our diet in order to have a body that is even barely acceptable.

It’s the idea that the body is inherently flawed—that science-fiction trope where the computer decides that the world is perfect except for those messy humans, who must be eradicated. In fact, I was going through page after page of Body of Art, thinking, “Those messy humans, yes, they must be gotten rid of. They keep messing everything up.” And I like that. So, our bodies tend to be the flaws in the system, and the book finds ways to celebrate the fleshy and smelly joys of our flaws.

Where would you say figuration fits into the landscape of painting at the moment?

I think we could pretty much guarantee that human nature is such that we will never be bored of looking at each others bodies, and not just strictly in a sexual sense. It’s just that human faces are really interesting, human butts are really interesting—everything about humans bodies in motion are interesting. In the same way, I feel like abstraction will never go away, because humans will never get bored of looking at colors. Looking at colors is what we’re ingrained to do. And bodies are intrinsically interesting.

The first instinct of any young artist who has some technical facility is to make a drawing of their friends, loved ones, and themselves, and that’s sort of the basis for everything that follows. Every truth in painting comes out of the fact that if you have the ability to make a picture you will make that picture, and that picture will probably be of someone you care about, or someone you’re angry at, or yourself, which can be all of the above.

I actually was just writing a catalogue essay for Sandro Kopp, a German painter based in Scotland who is famous for is doing portraits of people via Skype. It’s because his studio is in Northern Scotland, and nobody really goes there to visit him. So I was saying that Skype is this tribute to how deeply we want human connection—how if we can’t see someone’s face, we want to see their face; if we can’t hear the way they laugh, we want to hear the way they laugh. This is whole history of communication technology.

With Sandro, when you look at his Skype portraits you can tell they’re done through a reproductive medium—there’s this weird blurring and this strange sort of time lag and the blue-green tint that Skype does—but they’re all about somehow trying to find the truth in human connection. It reminded me that we’re always going to have a desire to look at other bodies, and find the truth in those human connections.

Sandro Kopp's No Bloody Privacy

Sandro Kopp's No Bloody Privacy

Who are the people Kopp paints? Are they commissioned portraits?

No, they’re all of people in his life that he cares about. He uses Skype the way we all use it. We tend to lead peripatetic lives, and there are always people who we’re not going to be with physically in the same country, but whom we still want a connection with. This technology makes that more possible, so he’s like, “Yeah, I can do portraits via Skype.”

That reminds me of the fact that one reason Chuck Close does his large-scale, minutely detailed portraits is that he suffers from prosopagnosia, or face blindness—he wants to use his art to forge the kind of sympathetic visual communion with his loved ones that his disease otherwise makes impossible.

Here’s another story. I was at a one-year-old’s birthday party recently, and there’s always this ceremony where they give the baby a big whipped cream cake and let them smear it all over the place. There were probably 40 adults in the room, each of whom probably took a hundred pictures of the cute one-year-old covered in frosting. I started doing the math: How many kids turn one every day? How many photos are there of these one-year-olds smeared with cake?

Because of the way we take digital pictures now, 99.99 percent of those are never looked at again—they’re recorded, uploaded to the cloud, and then they just exist as dust in the wind. It’s like when your computer dies and you lose a bunch of old photos, you really don’t even remember what you lost. You’re just kind of like, “Oh, yeah, sorry, I don’t have the photos of that anymore.”

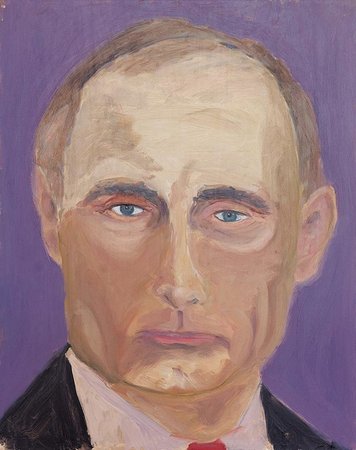

The transitory nature of these images now makes the idea of painting someone significantly more important, because it means you actually have to look at their face for longer and really invest time in what they look like. Some time ago I had the rather interesting experience of being asked by People magazine for a quote on George Bush’s paintings, and honestly our press person here at the museum advised me not to do it. She said, “This is a no-win situation—you’ll either come off smart but snarky or very silly.”

Actually, the quote came out well. It was: “This is clearly the work of an advanced amateur who looks at good sources like Chaim Soutine, and what’s interesting is that he’s painting world leaders whom he actually knows and could call on the phone. The bad thing is that he paints them from familiar photographs from the Internet.” What’s far more interesting is when you see paintings that are still painted from life.

George Bush's portrait of Vladimir Putin

George Bush's portrait of Vladimir Putin

To go back to the idea that we take countless digital photographs that we then never look at again, there’s actually one variety of digital image that we accord lasting value: the profile pic. You’ll have 50,000 pictures taken of yourself, or you and your girlfriend, and maybe one of them will be good and express the things that you hope to express. You then exhibit this portrait as the showpiece of your little gallery on Facebook, or LinkedIn, or where-have-you, and it becomes a very important part of your contemporary self-image. Yet, at the same time that portraits are so crucial, the commissioned portrait painting is still very much out of fashion.

With one crucial exception: pet portraits.

Really?

Yep. I don’t know if you know Andrew Ehrenworth, a New York artist I showed when I was at White Columns who was doing really interesting, brushy, semi-abstract paintings of dogs at the time. And it turns out the one part of the art market that never goes into a depression is portraits of pets. Everyone wants a painting of their dogs. In fact, when I got back in touch with Andy recently via Facebook, it was because I have a few dogs now—I commissioned two dog portraits from him, and I have them up on my walls. It was a fascinating thing, and I happily paid the money for it.

What about it terms of personal portraits? Why don’t we go out there and commission artists to make portraits of ourselves anymore?

Well, it still happens, and occasionally I get people calling me to ask if I know any artists who could to it. But the thing is, I only know artists who would do it in the weirdest ways. Do you know David McGee?

I don’t think so.

He’s an artist who shows at Texas Gallery, and someone I knew wanted to commission a portrait of himself and his mother. David learned that when my friend was a teenager, he and his mother would sit around and listen to Chaka Khan records together. So the painting ended up showing the mother and the son as tiny figures in the corner, and Chaka Khan really big in the front. In a way, it’s the perfect portrait of their relationship.

One challenge of traditional, non-commissioned portraiture is that it takes a certain kind of collector to want to buy an emotionally demanding picture of a stranger and put it in their home, where, whenever you look at it, it looks back at you.

It’s interesting, though, to see portraits that have gotten tamed over time. For instance, if I see an Alice Neel in someone’s house, I think about how weird they must have looked when she was first making them, and how classic they look today.

How do you think that shift operates?

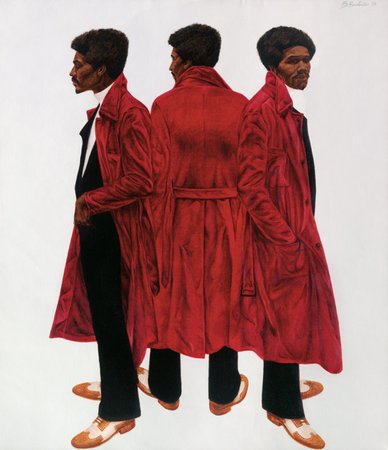

Well, I think she’s just such a beloved figure that people don’t necessarily look at what they are seeing when they look at her paintings—they just see an Alice Neel. A couple years ago, we had a Barkley Hendricks retrospective [at CAM] that was touring and at the same time the MFA had an Alice Neel show across the street. I got to spend a lot of time going back and forth between the shows and thinking about the different ways they depicted community, because when Alice Neel was in Spanish Harlem she was painting the people in her neighborhood, and Barkley Hendricks paints the people in New London, Connecticut. These are both communities that have been stressed, and both artists had a sense that they had to depict them before they were gone. But the thing about Barkley Hendricks is that, when I see his paintings in people’s houses, they still look weird as could be.

Barkley Hendricks

Barkley Hendricks

Do you see the person rather than the aesthetic?

Yes. Just because of their hyperrealism, and their more vernacular, street kind of dress.

It’s fascinating how much this kind of context determines how we understand images of the body.

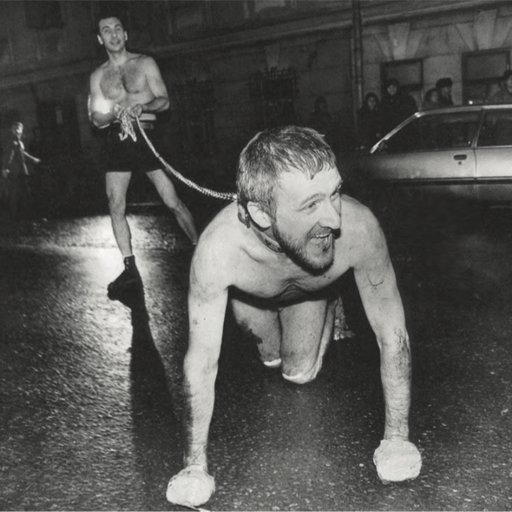

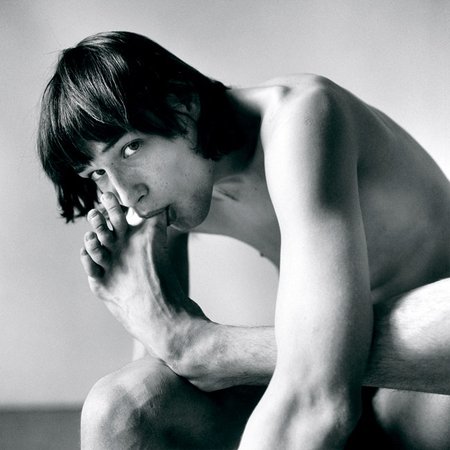

I wrote an essay for a museum in Italy last year, about a show of work by Jack Smith, Peter Hujar, and Robert Mapplethorpe and how we now receive images that used to be seen as marginal. I talked about the Peter Hujar photograph of the boy sucking his toe at length, and how it used to be that 90 percent of the audience who would walk in to a show like that and see this image would say, “This isn’t for me,” and walk out. Now, that’s no longer the case—the margin has shifted. My essay was actually called “People Don’t Suck Their Toes Like That Anymore.”

Peter Hujar

Peter Hujar

That image, which is in Body of Art, is certainly still arresting—but I suppose respectable society doesn’t have the same fight-or-flight response that they might have had in the 1980s.

The whole context has changed. Another thing I wrote about in that essay is the famous triptych by Hujar of the New York City Ballet dancer naked in a chair masturbating, coming on his stomach, and then recovering. Unlike most of the subjects in Hujar’s photographs, I didn’t know who he was, and I just assumed because so many of his models had died from AIDS, drugs, or suicide that this young man had come to a bad end. It turned out he hadn’t. He had an unusual name, so I looked him up online and ended up finding out that he had married his partner in Provincetown a few years ago and put the entire wedding ceremony up on Vimeo. I thought, if exhibitionism in 1972 means masturbating for Peter Hujar, and if exhibitionism today means putting your gay wedding up on Vimeo, then that is clearly a watershed change.

You mentioned earlier that a difference in portraiture today is that it’s no longer solely the province of male artists. How are female artists depicting the body today in ways that push the envelope?

We just had a Marilyn Minter show, and it’s still a challenge to show the porn paintings from the late ‘80s. Back then it was unheard of for a woman to depict hardcore porn, and this grid shows four blowjobs, three women blowing men and one of two guys. Our first question was, how do we isolate those paintings? Because even today, two decades later, you cannot have a general public audience with kids walking into see blowjobs. So I went to see the Koons show and I just sat in the “Made in Heaven” room watching how the guards were interacting with young people who wanted to go into see it but were too young, because I knew it would be the same issue for us. It was totally fascinating. There were even some tours for adults where the tour guide wouldn’t take them into the porn room, because this is not considered accpetable even today. And Marilyn’s porn grid is a crucial part of her story—you can’t do a survey of her career without it—but it still makes people very, very uncomfortable.

The kind of sexually explicit, almost brutally blunt portraiture seems about as far from abstraction as you can get.

I would probably argue that it’s actually a different type of abstraction—the abstraction of sexuality.

If you were to curate a show about painting at this moment in a way that would be the next pendulum swing away from the “The Forever Now,” what would its focus be?

I’m always working on shows, and I get to do a curatorial project every few years. I was looking at the poetry of Hart Crane, where everything is really abstract but then all comes back to real narrative. I had this idea of doing a show, which I will probably never get a chance to do, called “Abstract Like Hart Crane,” which would be a show of almost entirely figurative work but that somehow dealt with the abstraction that is interpersonal relationships. Because we always talk about the formal relationships in works of art. But I have a staff of 22, and I can look at the tensions between the departments and different people and see them almost visually. Looking at a Richard Serra, it’s a lot easier to handle that, with its weight and relationship to space.

To end on a note about Body of Art, is there anything in particular that you enjoyed about it?

The thing I liked the most about Body of Art as a contemporary-art guide is that I get very nervous when students don’t understand that there’s a continuum running through all of human creation, and that you have to look cross-culturally as well as across time in order to understand it. I like that the book shows that with an active visual imagination, and makes these connections clear.