“Tonight I have cooked up—let me use your language—‘curated’ a show tonight,” the artist Jibz Cameron joked in the opening monologue of “Good Morning Good Evening Feelings,” her one-woman motivational variety show at the Kitchen last April. Cameron, performing as her spandex-clad, rubber-faced alter ego Dynasty Handbag, wore pancake makeup and an ill-fitting fluorescent pink satin waistcoat over a flesh-colored unitard. “I hope no one was thinking they were gonna see art,” she goaded the audience. “Are there art people here?” The ensuing lighting-fast hour included a lesson in how to make a smoothie out of immaterial fears and anxieties, an incoherent karaoke rendition of Madonna’s “Vogue,” and an interview with Womanhood (personified by a British-accented cartoon crotch in white panties.)

Cameron’s performances, which draw liberally from the conventions of standup comedy, are undeniably funny—but they also represent a new hybrid art form. From Jaimie Warren’s bizarre vaudeville to Jayson Musson (a.k.a Hennessy Youngman’s) viral Youtube sendups of art world orthodoxies with a dose of hip-hop swagger, contemporary art and alternative comedy have never been more intertwined. In certain cases, they’re indistinguishable.

Dynasty Handbag

Dynasty Handbag

“It’s a cultural zeitgeist thing. I think standup is having an interesting moment, a kind of renaissance,” says Jill Dawsey, curator of the recent “Laugh In: Art Comedy Performance” at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. She counts experimental comics Maria Bamford and Reggie Watts among those who have expanded the genre to embrace unprecedented weirdness. “There’s this formal kinship where there are more experimental comedic acts that resemble performance art, and then there are a lot of artists who are doing something more like standup comedy.”

No longer at the margins of the art world, practitioners combining art and comedy are now attracting critical buzz and institutional recognition. In 2013, New York’s Maccarone Gallery mounted “On Creating Reality, by Andy Kaufman,” a scholarly exhibition of artifacts from the influential experimental comic’s estate. This summer, Art in America published an issue dedicated to “comedy in contemporary art.” The most recent New Museum Triennial, a weathervane for emerging art trends, featured a new digital standup act by artist/comic Casey Jane Ellison. Visitors could see the artist’s bald, dead-eyed digital avatar performing a disjointed post-human comedy routine full of jokes about millenials: "We all, you know, spend our parents' money on sustainable businesses."

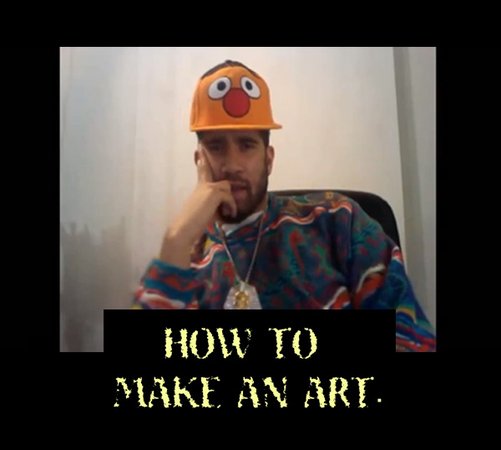

Hennessy Youngman

Hennessy Youngman

Why is the art world suddenly taking comedy so seriously? Artist and “concrete comedian” Sean Patrick Carney, who has led seminars on and written about the intersection of art and comedy, identifies art’s recent comedic turn with a renewed sense of political urgency. “People are frustrated and pissed off, justifiably so, about multiple social issues around race, economics, misogyny—you name it. We're well past the niceties in art that followed September 11,” he said in an email interview. “Are these social injustices themselves funny? Absolutely not. But the institutions that make them manifest are laughable. There's a feeling of individual power in taking the piss out of something that aims to marginalize somebody.”

Dawsey thinks comedy’s cultural ascendance is “symptomatic of a very dire political situation” where comedy has emerged as a privileged space of political expression. Jon Stewart stepped down as host of the Daily Show a few weeks ago, launching a thousand think pieces about the fact that America’s most influential mainstream liberal pundit was a comedian. “There’s something about the space of comedy that allows difficult questions to be heard,” she says. “Bill Cosby and the accusations of rape that have followed him for years could only emerge and be taken seriously within the context of Hannibal Buress talking about it on stage, and specifically from a male comedian.”

Casey Jane Ellison

Casey Jane Ellison

At a moment when comedy’s cultural currency is on the rise, several artists— a good number of them non-white or non-male—have used comedic personas to send up the art world and its critical pieties. Ellison, for instance, smuggles sharp critiques of patriarchy and elitism into a performance of millennial vacuity. Armed with a Kardashian-grade vocal fry and an unimpeachable deadpan, she plays a disaffected, lethally hip host in her all-female talk show, Touching The Art (several episodes were screened in the New Museum Triennial.)

“Don’t you think it’s so funny how women can’t sell their art?” she asks, tongue firmly in cheek behind her black-painted lips, during a segment on art world inequality. “You all look gorgeous,” she tells panelists Catherine Opie, Bettina Korek, and Jori Finkel in the show’s inaugural episode, before backpedaling: “I don’t know why I had to comment on your appearances. I think it’s the subtle expectations of institutionalized sexism.”

The comedic alter ego, of course, is not entirely a new strategy. It can be traced from Marcel Duchamp’s drag persona Rrose Sélavy to the puerile and scatological performances of Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, and Michael Smith. In 1996, artist Guy Richards Smit created the sweaty, semi-functioning alcoholic sleazebag painter Jonathan Grossmalerman as a parody of the macho bombast associated with eighties Neo-Expressionism. In the character’s 1996 debut, Grossmalerman—whose name roughly translates to ‘Big Painter Man’ in German— delivered a hacky, misogynist standup act to an imaginary audience. “Why would I need to beat up my wife when I have an artist’s assistant?” he joked, his tinny punch lines followed by an uncomfortable silence.

Guy Richards Smit's Grossmalerman

Guy Richards Smit's Grossmalerman

In Smit’s new sitcom— shot at Brooklyn’s Pierogi Gallery and featuring Cameron as the artist’s girlfriend and muse—Grossmalerman is now a pathetic also-ran, holed up in a Bushwick loft churning out humungous Alex Katz-style paintings of genitals. “We’re just not sure that large-scale Pop art depicting vaginas with, but also just as much without, penises in them is quite the cultural slam-dunk it used to be,” quips a visiting dealer in the show’s first episode.

There will always be a place, it seems safe to assume, for this kind of art-world satire. But the new comedic art goes beyond it, probing the boundary between weird standup and performance art. Experimental comic Kate Berlant, who performs in museums and galleries as well as conventional standup venues, peppers her act with readymade academic words like “subjectivity” and “materiality,” creating a verbal collage of self-help messianism and theory-inflected psychobabble. “As a woman, you kind of want your father to sexualize you,” she muses in one of her acts, “and that’s kind of the only currency available.”

Another crucial aspect of the new art comedy is its relationship to identity. While conventional standup tends to rely on what Dawsey calls “the candid revelation of the comedian’s personal life,” the new art comedy, she says, “exaggerates the performance of selfhood.” One might think of it as thornier, more rebellious form of identity politics. As Berlant wrote recently in Art in America, “For me, stand-up was a form of resistance. I wanted to say: ‘I’m a woman, but I refuse to be what you think a woman is’ and ‘I’m a comic, but I refuse to be what you think a comic is.’ Now I’m apparently an art comic, but I refuse to be what you think an art comic is. I don’t want to be humiliated by a category.”

The artist Kate Berlant

The artist Kate Berlant

While the work of these new artist-comedians reinvigorates issues of identity and opens up space for a new kind of experimental performance, it also happens to dovetail quite conveniently with the kind of entertainment-oriented, event-based programming that's now a curatorial imperative. As Carney says of the genre’s newfound acclaim, “Part of it is a genuine interest in promoting what artists are doing now, part of it is figuring out how to monetize it and turn exhibitions into public spectacles with an entertainment factor.”

Dawsey is conscious, meanwhile, of the potential de-clawing effect of museums and other institutions on the new art comedy. “Everything is about experience and participation, and I think that that’s dangerous,” she says. She believes, however, that “really good work always exceeds that context.” The curator invokes Stanya Kahn’s 2012 video Lookin' Good, Feelin' Good where the artist, dressed in a foam penis costume, takes the stage at a comedy club to relay a story of childhood trauma. “I think that work is so challenging and complex, and yet it also has these moments of levity and joy.”