The Vienna of the past looms large in the popular imagination, with the Hollywood film Woman in Gold bringing Gustav Klimt's portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer to the big screen and high auction estimates for another painting by the artist, Portrait of Gertrud Loew, making headlines in advance of a Sotheby's sale. Even the first Vienna Biennale, which opens next week, is something of a throwback to the days of the Vienna Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte in its emphasis on architecture, design, and the applied arts.

There's a reason for the time warp. As the 14-year-old Neue Galerie has shown, the Vienna of that era was a vital, internationally-minded, interdisciplinary art center that continues to fuel new books and exhibitions—including one timed to the release of Woman in Gold, starring Helen Mirren and based on the story of the museum’s trophy painting, Klimt’s heavily gilded Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. “Klimt, in particular, has become not just a superstar but a mega-star,” Peter Vergo writes in the introduction to a new edition of Art in Vienna 1898-1918.

The past couple of years have also seen a flowering of Vienna Secession and Wiener Werkstätte-influenced activity by contemporary artists. Taking inspiration from multitasking aesthetes such as Koloman Moser, Josef Hoffmann, and yes, Klimt, they are orchestrating erudite and sophisticated mixes of art, architecture and design. Below are five noteworthy artists who have been studying Vienna intently (one of whom even lives there).

Exhibition view: Sarah Crowner, "Everywhere the Line Is Looser," Casey Kaplan, New York, 2015

Exhibition view: Sarah Crowner, "Everywhere the Line Is Looser," Casey Kaplan, New York, 2015

In her pieced-fabric paintings and ceramic-tiled floors, the New York-based artist Sarah Crowner turns little scraps of design history into contemporary geometric abstractions. Crowner’s recent solo exhibition at Casey Kaplan, “Everywhere the Line Is Looser,” included a bold blue-and-white work based on a fabric pattern by the Wiener Werkstätte co-founder Koloman Moser. Werkstätte references were just as prominent in her previous New York show, at Nicelle Beauchene in 2014, where turquoise ceramic floor tiles were laid out in a herringbone pattern derived from Josef Hoffmann. Specific visual cues like these are certainly important to Crowner, but so is the overall spirit of Vienna circa 1900 to 1920. As she told Artforum in 2011, “I’m thinking about moments in the early twentieth century when the avant-gardes were collaborating freely and cross-pollinating from music to theater to painting to poetry.”

Josiah McElheny, Study for the Center Is Everywhere, 2012. Brass, cut lead crystal, electric lighting, hand-bound book

Josiah McElheny, Study for the Center Is Everywhere, 2012. Brass, cut lead crystal, electric lighting, hand-bound book

84 x 32 inches, installed 6 inches above the floor; book approx. 7 x 10 inches.

Working mainly in glass, the sculptor Josiah McElheny revisits Modernist theories, movements, and leaders and gives them a dazzling new visual identity. His interests are highly specific and sometimes obscure—the 19th-century German writer Paul Scheerbart and the contemporaneous French socialist Auguste Blanqui have figured in his projects, as have better-known talents such as Carlo Scarpa and Alexander McQueen—but early-20th-century Vienna is a frequent source of inspiration. McElheny reviewed the Neue Galerie’s 2007 exhibition “Josef Hoffmann: Interiors, 1902-1913” for Artforum, and has made focused homages to Hoffmann and Adolf Loos that include an all-white re-creation of Vienna’s Adolf Loos-designed “American Bar” and the Hoffmannesque brass and crystal chandelier, pictured above, from his 2012 solo exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

VERENA DENGLER

An installation view of Verena Dengler's exhibition at MAK (Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art), Vienna, 2013.

An installation view of Verena Dengler's exhibition at MAK (Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art), Vienna, 2013.

Based in Vienna, Verena Dengler is surrounded by reminders of the city's historical avant-gardes. A sort of one-woman Werkstätte, she uses painting, embroidery, graphic design, and sculpture in her sprawling installations (one of which was a standout at this year's New Museum Triennial). Some of her works pay homage to undersung female artists from the Vienna scene, as in her Sculpture für Camilla Birke und Maria Likarz, Wiener Werkstätte; others, like her 2014 self-portrait The Verena Complex, explore the city's well-known contributions to the field of psychology. Dengler is currently showing canvases adorned with both paint and needlepoint at the Thomas Duncan Gallery in Los Angeles, in a show with the tongue-in-cheek title "American Painting" (through June 20).

Lucy McKenzie's Loos House, 2013, at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

Lucy McKenzie's Loos House, 2013, at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

Trained as a decorative painter, the Brussels-based artist Lucy McKenzie has long had an interest in the ornamental surfaces of Viennese architecture and their connection to the Arts and Crafts movement in her native Britain. (The architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh, a fellow Glaswegian, had close ties to the Vienna Secession). Her interests also extend to non-Western design; McKenzie's 2013 show at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam included both a faux-marbled model interior inspired by Adolf Loos's Villa Müller in Prague and panels reproducing Arabic motifs from the Alhambra palace in Granada. McKenzie's works may not always look like they were made in fin-de-siecle Vienna, but they remind us that the Secession and the Werkstätte were defined by collaboration and openness to outside influences.

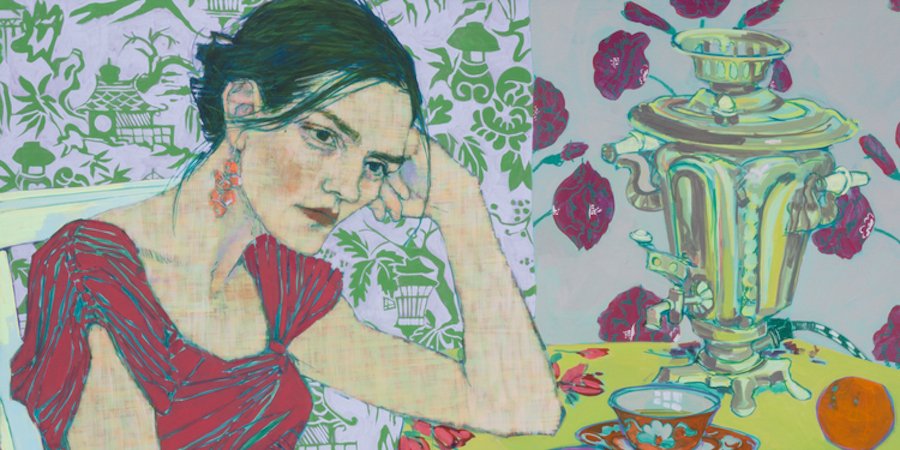

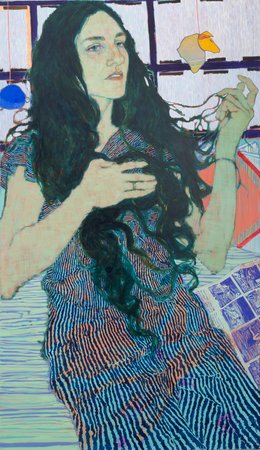

HOPE GANGLOFF

Hope Gangloff, Catherine, 2015. Acrylic on canvas, 62 x 36 in. Courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery.

Hope Gangloff, Catherine, 2015. Acrylic on canvas, 62 x 36 in. Courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery.

The painter Hope Gangloff specializes in portraits with strong contour lines, jewel-like color and abundant decorative interest—works that have earned her frequent comparisons to Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt (especially when her subject is a pale young woman with flowing locks and a striated dress, as in the painting above from her current show at Susan Inglett in Chelsea.) "I like to collect colorful things that inspire me. I have yards and yards of fabric, and clothes I could never wear but that have a good pattern," she told Artspace in 2013. The connection isn't just a formal one; Gangloff depicts friends and family from her own closely inscribed arty circles in Brooklyn and upstate New York, foregrounding her bohemian lifestyle just as Klimt did in his sandals and smock.