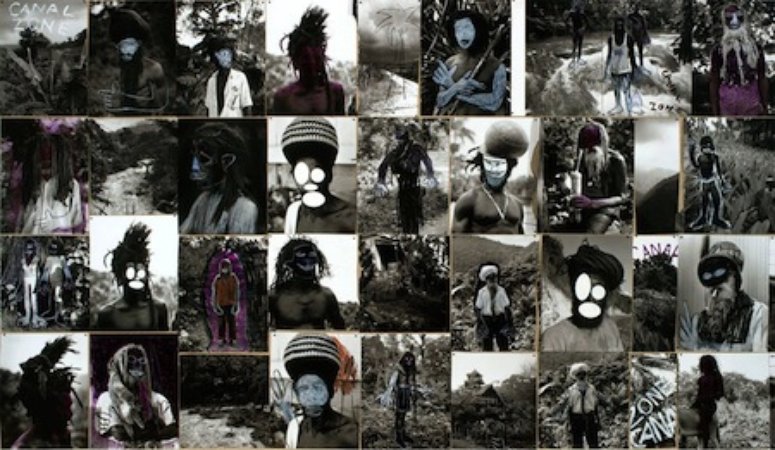

Is there anything left to say about Richard Prince's notorious "Canal Zone" paintings and their attendant legal controversy? The case was finally settled, leaving its effect on copyright law uncertain. Art-world scolds who railed against Prince's appropriation of photographer Patrick Cariou's Rastafarian images have moved onto new causes. The dozen or so pictures, looking as if some of them might be new but all dated 2008, are now on view at Gagosian Madison Avenue, filling both the main sixth-floor gallery and the long, tall space on five.

Prince's "Canal Zone" series figured in my favorite giveaway at Frieze New York, the first edition of Gagosian's 32-page tabloid newspaper. The publication—a galley 'zine?—includes Prince's apocalyptic fantasy, a kind of short story titled "Eden Rock." The tale, which Prince characterizes as a cross between The Lord of the Flies and a zombie movie, begins with an island-hopping Caribbean vacation interrupted by nuclear holocaust, with the resort civilization soon collapsing into battling tribes. Tourists on the ships, waiting to be rescued and taken care of, are easy pickings for marauders, but the seven-member cruise-ship reggae band is savvy, holing up in a resort hotel located on an easily defensible spit of land. The story is not unlike J.G. Ballard's 1975 grim novel High Rise with a dash of Prince's signature insouciance.

James Brown Disco Ball (2008)

James Brown Disco Ball (2008)

The plot—if one is aware of it—makes the pictures immediately legible, which at first seems to lessen them somehow. Who gives their paintings a "plot" anymore? Don't we prefer our art to be open, allusive, even gnomic, rather than closed down by a determinate narrative?

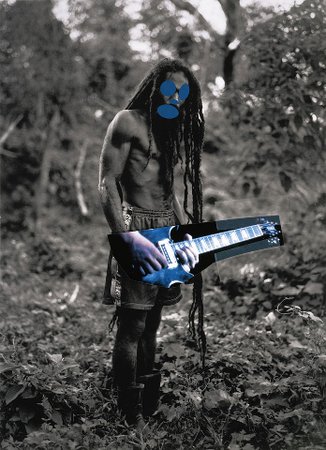

We can't be blamed for thinking that maybe Prince was backed into this position by the legal assault on the works. Certainly, the appeals court was still not satisfied with this explanation, concluding that five of the "Canal Zone" pictures were insufficiently altered to be fair use. The judges read nothing into the straightforward photos of Cariou's Rastaman, adorned by Prince only with a cut-out guitar and solid-colored circular shapes on eyes, ears and mouth. The easy reference of these images to the mask-headed nudes in Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon was not enough, apparently.

Graduation (2008)

Graduation (2008)

Me, I was ready to be called as an expert witness. The "Canal Zone" pictures were critical commentary on the domestication and commercialization of Rastifarian culture. The guitar transforms the Jamaican man into a music-industry construction sold as an ethnographic fantasy of primal freedom. The abstract "coins" on the figure's eyes are a classical reference to the fee due to Charon, the Greek ferryman of dead souls across the River Styx. With the "Canal Zone" pictures, then, Prince is declaring an end to the colonialist myth of any kind of island Arcadia.

Except of course that Prince testifies that he knew nothing, really, about reggae music or Rasta culture. My expert opinion, while not necessarily wrong, is certainly tendentious. Ironically, such is the upshot of Cariou v. Prince—i.e., the interpretation of the artist, or of a judge (or critic), does not exhaust the potential for meaning in the work.

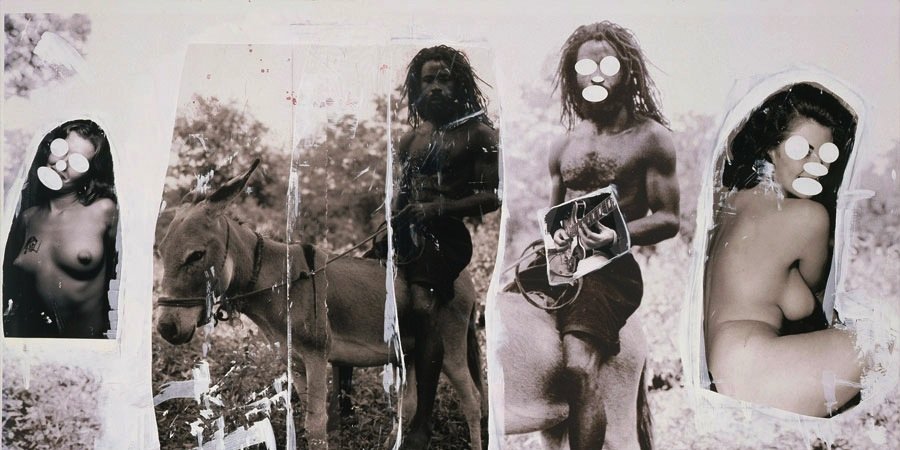

Cheese & Crackers (2008)

Cheese & Crackers (2008)

With the legalities out of the way, we can ask another question. How do the pictures look now? In a word, they look hot. Prince has devised a carnal bordello of pseudo-AbEx brushwork, both abject and noble, peopled by images of a single untamed man and variety of female pinups. One notable detail, a fecund marijuana patch surrounding the standing figure, reflects Cariou's own artistry, and seems an interloper here. Most of the other characters are generic, their specific identities occluded behind hand-drawn masks, like in some rawer version of the orgy scene in Eyes Wide Shut. And yes, as we might expect, the female figures exhibit themselves, while the male solemnly examines us.

In distinct contrast to much art that is favored by the market, it's difficult to imagine "Canal Zone" as interior decor. In what wealthy home could they be displayed? The pictures are intoxicated, indecorous, avidly heterosexual. They're a contemporary bacchanal, and one that mixes the races at that. They proudly reject bourgeois family values.

The Canal Zone (2008)

The Canal Zone (2008)

But if it's a bacchanal, what god do these pictures celebrate? Our avant-garde could be characterized as a secret cult devoted to freedom (if not liquor and drugs). Is the "Canal Zone" simply another dystopia, where human nature is reduced to a stupor of the senses? Is this jungle paradise a setting, once again, for a fable telling of the fall of humankind? It certainly comments upon nature, of both the human and ecological sort. And it is emblematically postmodern, illustrating the way our response to the world is made through texts and fictions.

Walter Robinson is an artist and art critic who was a contributor to Art in America (1980-1996) and founding editor of Artnet Magazine (1996-2012). His work has been exhibited at Metro Pictures, Haunch of Venison, Dorian Grey, and other galleries, and he has a new show opening at Lynch Tham on May 28. He can be reached at walter@artspace.com. Click here to read his previous See Here column on Artspace.