At a panel last month on the Whitney Biennial—an installment in the series of monthly reviews of New York art shows organized by Artcritical editor David Cohen and held at the National Academy Museum on Fifth Avenue—the critic Joe Wolin framed the current installment of the always-controversial exhibition with notable economy. The biennial has three curators, two men and a woman, he said, and the gender breakdown of artists in the show is about the same proportion.

Then Wolin unloaded another observation: the show is almost entirely white, an especially peculiar condition considering the exceptional work currently being made by black artists.

He was right, of course, and my first impulse was to search for an alibi—a term I use in light of the Museum of Modern Art’s perplexingly titled show "Sigmar Polke: Alibis," which I take as a allusion to the struggle of individuals to unburden themselves of a collective history. As a white guy, I felt guilty, and would prefer to be off the hook. I glanced around the room, and the audience was as pale as a glass of milk. Maybe black artists had something better going on somewhere else? In that case, the whiteness of the Biennial is its own punishment.

A second thought was that the inequity could be addressed institutionally, i.e. with a black curator. The Whitney once boasted one, Thelma Golden, who in 1994—20 years ago—organized a provocative survey of "The Black Male: Masculinity in Contemporary Art." Golden is now director of the Studio Museum in Harlem, which is certainly one place that black artists and a black audience can be found. (MoMA, it might be added, recently hired the African-American curator Darby English to build out what he described as "a black direction" in its programming.)

Rebalancing the art-historical scales remains a fruitful museum undertaking. At the Whitney itself we soon will have a full-scale survey of “Jazz Age” painter Archibald Motley (1891-1981), scheduled at its new downtown redoubt in 2015. The show was organized by art historian Richard J. Powell for Duke’s Nasher Museum, where it is just closing before embarking on a national tour.

Still another thought: I like the way that Wolin’s stats are clear, simple, and apparently definitive, but don’t give us much in the way of aesthetic assessment. In that, stats are a parallel measuring scale like the art market, which also doesn’t always have a trustworthy relation to artistic value. Needless to say, in its own modest way, the art market is doing its bit to integrate the art world, elevating—if that’s the right word—Jean-Michel Basquiat to emblematic status and including works by David Hammons and Glenn Ligon in high-profile evening contemporary-art auctions. And no doubt you've heard of two young market favorites, Oscar Murillo and Lucien Smith.

My final impulse, still sitting in the audience at the National Academy, was to take a quick mental census of the biennial, since Wolin provided no details. The problem is, of course, that biography isn’t always evident. Of more than 100 artists, I knew two who are black, the late sound sculptor Terry Adkins and the photographer Dawoud Bey. There may be more; I know that the exhibition also includes a Puerto Rican, a Native American, and an Asian guy from Hawaii.

If that sounds a little absurd, it’s supposed to. Race is a subject that has all the fascination of a hornet’s nest, and if I’m going to poke at it, I’d prefer to use a light touch.

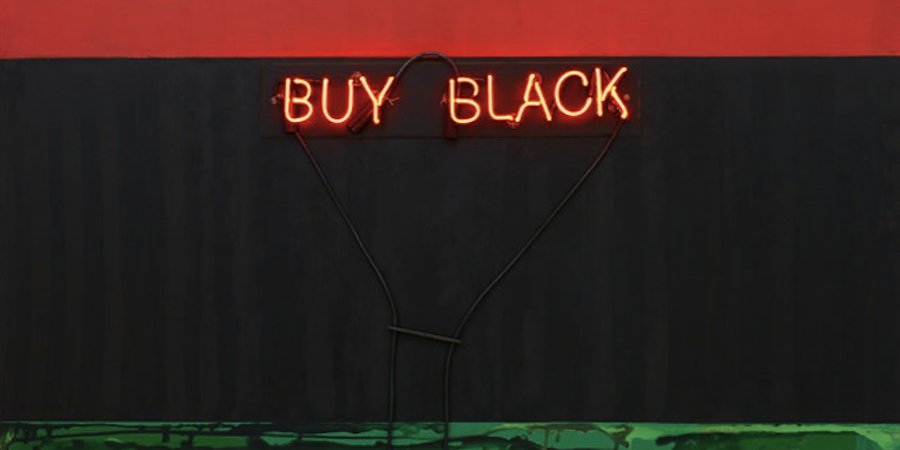

So with that in mind, let’s take a look at a new show that seems to say, “Biennial? We don’t need no stinkin’ biennial!” Such is “Black Eye: The 21st Century Black Identity Experience,” a show of 26 black artists organized by Nicola Vassell, a former director of Deitch Projects and Pace Gallery. A good number of the artists are already museum and market favorites, including Sanford Biggers, Nick Cave, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Hammons, Rashid Johnson, Kerry James Marshall, Wangechi Mutu, Jayson Musson, Steve McQueen, Rashaad Newsome, Gary Simmons, Hank Willis Thomas, Nari Ward, and Kehinde Wiley.

The rest would qualify as new talent, including Brooklyn photographer Deana Lawson, currently a lecturer in photography at Princeton, who contributes a color photo of three black women, naked, posed like chorus dancers on a humble basement set; the Rio-born thirty-something artist Christian Rosa, whose spare paintings have been compared to Twombly and Miró; and Tony Lewis, whose elaborate text pieces made with rubber bands, graphite, and nails urges readers to flush urinals with their elbows rather than their hands. (Lewis is in the biennial, as it happens, and I saw a show of his at Shane Campbell Gallery in Chicago, though without realizing he was black). “Black Eye” is on view through May 24 at 57 Walker Street in TriBeCa (just next door to the Artists Space annex). The website is www.blackeyeart.com.

My general reaction? Art responds well to pressure! The diffuse race-consciousness—racism?—that surrounds us has a salutary effect on art that addresses it. The art becomes more socially relevant and biting. Artistic invention aligns with the quest for freedom.

The Zimbabwean artist Kudzanai Chiurai’s large color photographs of menacing African militiamen recall the continent's continuing struggle with colonialism. And Kehinde Wiley’s giant painting of a black Judith decapitating a blonde female Holofernes suggests, with a jovial brutality, that Judith would prefer to be done with white standards of beauty.

There’s more. In the storefront’s darkened basement, Duron Jackson, who got his sculpture MFA from Bard in 2010, has a video projection called “Gladiator School,” showing what looks like a ghetto schoolyard beatdown. That’s macho! And Rashid Johnson’s contribution is a life-sized, color photograph his own naked beautiful self, done in 2005 in homage to Barkley Hendricks. He’s letting it all hang out (as critic Linda Yablonsky joked at the opening) in a way that is nothing if not triumphant.

A bit of more mockery of white people is also on hand, notably in Jason Musson’s large text piece, My Million Dollar Idea (Too Black for BET), which describes a putative reality TV show called “Find the White Neighborhood,” which would involve having white contestants try to find their way out of black areas. Ha ha.

More complicated is a lenticular text work by Hank Willis Thomas which overlays two statements—"Black is Black," and "Black is White"—which would appear to question the ability of black people to hold onto their own identity in a majority white society. Just what does it mean to be successful in a white-dominated business? In this regard, curiously, was a point made in an article titled “The Whitney Biennial for Angry Women,” which criticized the biennial for including Dawoud Bey’s portrait of Barack Obama as a sign of a presumably despised “liberal democracy” and “open code for the newest American myth: the multicultural, progressive future.”

Me, I’d rather think of it as an ideal. In her “manifesto,” Vassell defines her show as utopian, and argues that the importance of race as a factor of self-identification is archaic. She’s right, and not just because it’s a good alibi.

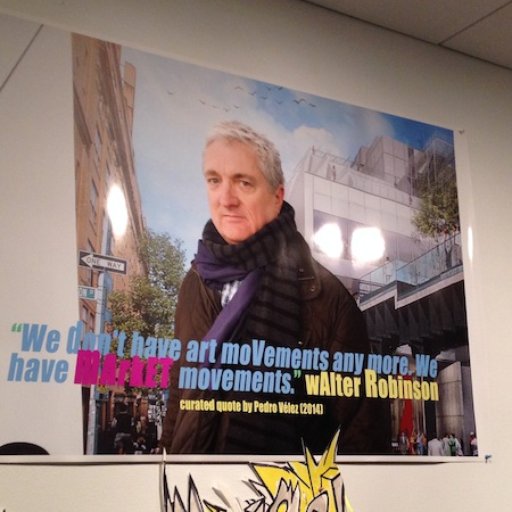

Walter Robinson is an artist and art critic who was a contributor to Art in America (1980-1996) and founding editor of Artnet Magazine (1996-2012). His work has been exhibited at Metro Pictures, Haunch of Venison, Dorian Grey, and other galleries. He can be reached at walter@artspace.com. Click here to read his previous See Here column on Artspace.