Does art have any magical powers? Do any serious artists today make claims on the realm of the supernatural? Is it foolish to pursue the notion that visual artifacts might have extraordinary effects, like amulets or mandalas or fetishes?

Plenty of people still pray to their saints and wear lucky charms, that we know. Early Christian relics like the Veil of Veronica, a miraculous product of Christ's passion, is said to have had the power to restore sight and raise the dead. By no mistake did Malevich display his essential 1915 Suprematist work, Black Square, in the corner of a room, a mystically significant position traditionally reserved for Orthodox Christian icons.

Despite Malevich's example, at first glance this kind of magic doesn't really play in the professional avant-garde. Neither artists nor dealers nor critics are likely to argue that some painting can make you well, or that a certain photograph will bring you good fortune, or that a sculpture or installation might help you settle things once and for all with your dead mother.

On the other hand, we know that art is supposed to be good for you, broadly speaking. According to a study by Americans for the Arts—one of many such research papers—teaching the arts to kids strengthens problem-solving and critical-thinking skills, not to mention helping them get better grades in school.

Art has plenty of other effects, of course, though we might not call them "magic." Expressionism is typically thought to be somehow cathartic, while surrealist and dream imagery may offer an assortment of psychic insights. Op Art plays undeniable tricks on the eye and the mind. In "Edge and the Art Collector," an essay for the literary journal n + 1, the author Gary Sernovitz mentioned his own preference for artworks that are "stiller" with "a contemplativeness," citing a rather generous range of artists: Hopper, Rothko, Newman, and Judd. And then there's erotica, which wields its own kind of (devil-possessed?) sorcery, though how arousing pin-ups by Richard Phillips, Mel Ramos, or Richard Kern are in a gallery context are a personal matter left to the individual.

More to the magical point perhaps are artists like Joseph Beuys, who was often cast as shaman; Yoko Ono or James Lee Byars, who played the guru; or even Anselm Kiefer, who can be seen as a prophet, Old Testament-style. We are talking here about the art world's own "eternal primitive," a special life force that powers all kinds of modernism, from Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and Dubuffet's Art Brut to the newly championed figurative expressionism of Thomas Houseago. None of this is exactly magic, but these examples do suggest a strangely potent atavism underlying our most avant-garde contemporary culture.

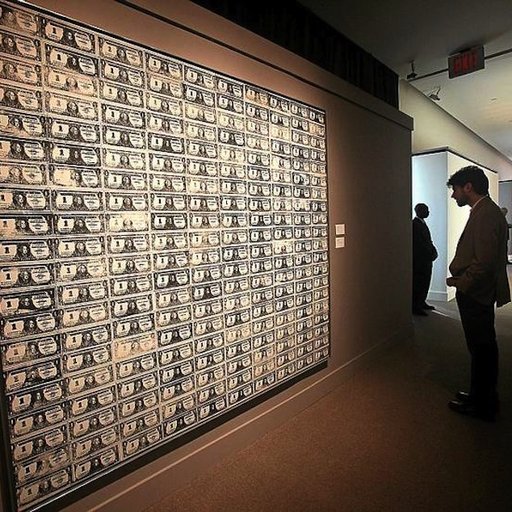

Strange, because however "aesthetic" the contemporary art experience may be, it appears generally to be moving in an analytical and even scientistic direction, i.e. away from magic. The entire enterprise of Postmodernism, including the Pictures Generation and institutional critique, seems designed to "deconstruct" a regime of domineering imagery, and thus somehow free us from a repressive social order in which photography plays a part.

(Such a result would indeed be magical, in a figurative sense, were it to be confirmed. Whether and how such goals might in fact be accomplished by images of cowboys from cigarette ads, photos of a young woman masquerading as an endless number of female types, or black-and-white renderings of atomic explosions or cathedral interiors, is perhaps a question for another day.)

It's revealing too in regard to the dichotomy of magic and science that the Light and Space artist James Turrell is presented both as some kind of conjurer and an expert in the psychology of perception. Tellingly, Roberta Smith's New York Times review of Turrell's magisterial new Aten Reign installation at the Guggenheim Museum felicitously describes it as a "meditative spectacle," but notes that its heightened visual experience is made possible only thanks to "considerable engineering expertise and... a good-size budget." Turrell sometimes comes off "a bit too much like a mystical seer," she notes.

Art still has social effects that are surely akin to magic, in the sense that they are phenomena that appear to arise independently of individual agency. The exhibition last December of Andres Serrano's notorious Piss Christ—then 25 years old—at Nahem Fine Art brought protesters to West 57th Street every day. And political observers await a repeat performance of the prestidigitation that brought us Shepard Fairey's Obama Hope in 2008.

I got on this whole "magic" kick after reading Walking Through Walls, the 2008 memoir by the Miami artist Philip Smith (which is now being made into a television series by Showtime). Though not that well known today, Smith is one of the original five artists included in critic Douglas Crimp's influential 1977 "Pictures" show, and a veteran of the 1991 Whitney Biennial. His father, Lew Smith, was a celebrated interior decorator—he popularized the beaded curtains that became a design fad in the '70s—who later became an influential psychic and healer, and the book is a fascinating account of a kid trying to grow up normal in an unusual environment.

Smith inherited his father's gifts, and may or may not have managed to put some clairvoyance and aura into his paintings. See for yourself this coming November, when Smith has his first New York exhibition in some time at Jason McCoy Gallery in the Fuller Building on East 57th Street.

Walter Robinson is an art critic who was a contributor to Art in America (1980-1996) and founding editor of Artnet Magazine (1996-2012). He is also a painter whose work has been exhibited at Metro Pictures, Haunch of Venison, and Dorian Grey Gallery. Click here to see his previous See Here column on Artspace.