The contemporary art world is flourishing. Despite all the grumbling—and we'll get to that in a moment—does anyone doubt that we are flooded with artists, overwhelmed by art shows, and swamped by art fairs and biennials? For better or for worse, has not the art world extended its tentacles to every corner of the globe, and sucked into its maw disciplines of every kind? Are not more words than could ever be read lavished on art every month in magazines, newspapers, and blogs, despite the woeful economics of the trade? And are not art prices—and we can never forget prices—higher than ever before?

Thirty years ago, the late art critic Craig Owens, in a backhanded slap at the East Village art scene, referred to "the overproduction of artists," as if they were so many widgets ordered up by the Central Committee. The art-world population explosion continues, as the Chronicle of Higher Education attests when it tallies the number of new bachelor's degrees in the visual and performing arts at about 93,000 per year, and the number of master's degrees at about 15,000.

Those numbers seem low to me. Indeed, the art workforce in New York is growing so fast that many of its members are obliged to work for free, and consequently have made the demand for "paid internships" a cultural issue. Need further convincing? Surely the School of Visual Arts's 2010 launch of a new Masters of Fine Arts in Art Practice program, founded and chaired by no less a macher than former star museum director David A. Ross, represents a new acme of the professionalization of the avant-garde, while the current Brooklyn Museum exhibition devoted to what must have begun as an art-student prank—the Bruce High Quality Foundation—institutionalizes it, albeit in an appropriately peculiar form.

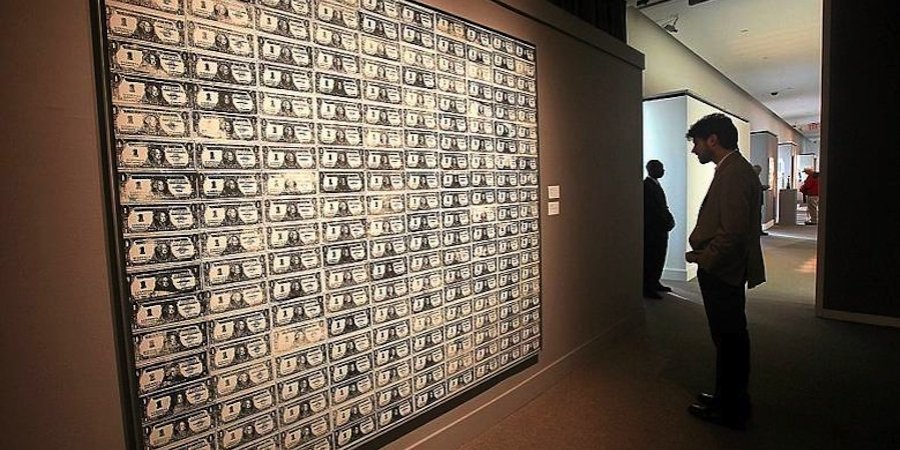

All this creativity is not birthed in an economic vacuum. The other day, my alma mater Artnet ran the numbers in its famed fine-art auction database and discovered that auction sales of art in the United States were up 7 percent, with the global auction market topping $7 billion. Over the past 10 years, Artnet announced, an index of 50 top artists had an annual growth rate of 17.7 percent, compared to returns of 4.9 percent a year for the S&P 500.

The people at TEFAF—the annual European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht—are a bit gloomier, seeing a contraction in the overall global art market of 7 percent for 2011-12, thanks to economic uncertainty. Still, the total is put at €43 billion for last year, or almost $59 billion. Not shabby at all for a down year.

And yet, and yet, all this good fortune is definitely clouded with melancholy. Everywhere you turn are pessimistic critics and commentators who diagnose an art world beset by troubles. The sun may be shining bright somewhere in this favored land, but in Mudville there is no joy to be found.

Critical thinking itself is in serious decline, argues Hal Foster in an essay titled "Post-Critical"—it's battered by conservatism, neglected by academics and museum curators, and dismissed by everyone else. The gallery show is dead, proclaims Jerry Saltz in a much-commented-upon essay (aren't they all), along with the artistic discourse that surrounds it, a victim of the baleful influence of the market and the not-so-baleful decentralization of the art world.

Complaints about the links between art and political power can be found all over, from the Brooklyn Rail ("insidious" and "grotesque," in the words of Martha Schwendener) to Artforum ("a scandalous fact," writes Tom Holert in an article titled "Burden of Proof: Contemporary Art and Responsibility").

Everybody has their ideas about what's wrong with the world, of course—that's what critics are paid for. Me, if I were prescribing, I would call for more art that is nakedly partisan in terms of U.S. electoral politics.

Even the New York Times got into the act a few days ago, with a front-page story fretting about "record-breaking, and startling" art purchases by the royal family of Qatar, which are estimated at $1 billion a year. This circumstance contributes to "the escalation of prices," not to mention fears as to the "big hole" in the market when the buying stops. Oy, such tsuris!

So, what's going on? A lot of things, but most plainly, the unavoidable fact is that the success of the avant-garde marks its failure. This is not news. We've been domesticated, no matter how fantastic and provocative we might be, into just one niche culture among many. We're fun, and good, and even progressive, but all the rest of it is fantasy.

It's not so bad, really, being ordinary. It solves a lot of problems. And if you want, you can find an intimation in this disconnect, like astronomers inferring the presence of invisible bodies by the bending of radar waves. It could be, just, that something is happening.

Walter Robinson is an art critic who was a contributor to Art in America (1980-1996) and founding editor of Artnet Magazine (1996-2012). He is also a painter whose work has been exhibited at Metro Pictures, Haunch of Venison, and other galleries; he currently has a new show on view at Dorian Grey Gallery in New York's East Village. Click here to see his previous See Here column on Artspace.