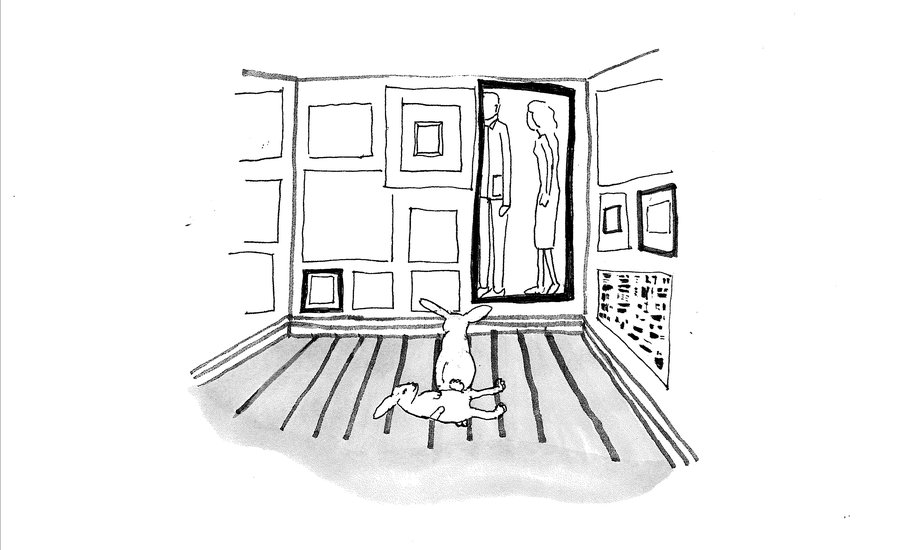

The term "collector" endows a person with a certain esteemed gravitas, or it rationalizes an innocuous obsession. Collecting is a compulsive behavior. Some people collect contemporary art; some people collect glass eyes, exotic sand, or Russian dolls. I have been collecting art and animals for a while now. Both are extraordinary. Both serve no applicable function. It has been proven that if you have a dog or a cat, you will live a longer life. (The impact of a menagerie has not yet been determined.)

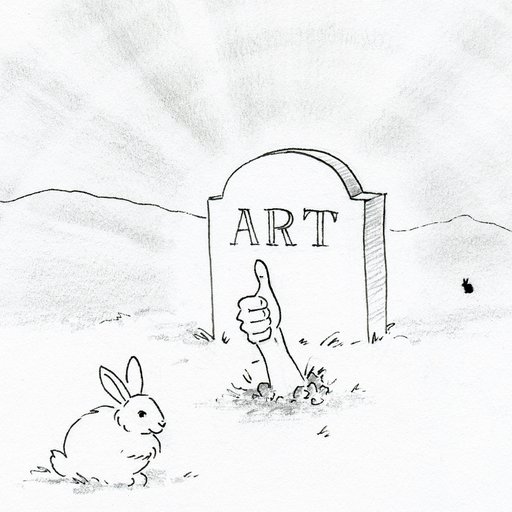

As for art, it doesn’t exactly increase your lifespan, like red wine or gluten free cookies might; it does, however, speak to longevity: you will have this forever and then it will outlive you. With animals, you love and let go. With art maybe it’s about holding on.

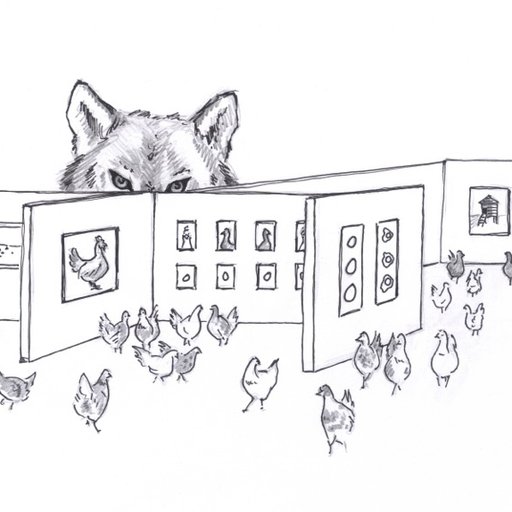

Someone recently texted me, "How many animals do you have?" My emoji response was an extended line of miniature cartoon heads with beady eyes: a concentration of eye contact. My husband believes that the persistent stare of our animals, namely our dogs, is an expression of entitlement. I think it’s an effective sales tactic. Our animal lineup is as follows: 3 dogs, 4 cats, 2 bunnies, 5 hens, 1 rooster, and 2 goats.

"What’s next," she texted, "a donkey?" I hadn’t considered a donkey, but at that moment deemed it a concept worth exploring further. No cows—too big and dumb. No pigs—too intelligent and greedy. No peacocks—too beautiful and bitchy. How many is too many?

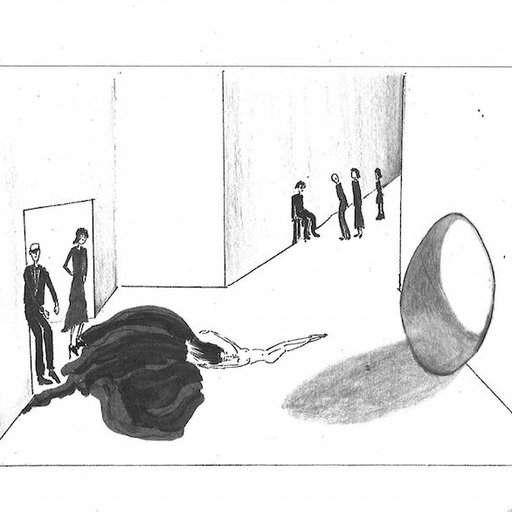

I’ve been to art collections where every inch of every wall is covered with contemporary art. Not knowing where to focus your eye has a dizzying affect. Yet there is also a reassuring feeling to these collections, where each object claims its own place and rooms arrange like the pages of a scrapbook. That is:

Each piece carries with it a personalized history: "This painting was acquired from a gallery in London after eating oysters for lunch and receiving an irritating phone call that was soon dispelled by the quickening enthusiasm for this fabulous find."

Each piece carries with it a specialized endowment: "This video is by an artist who went to Yale or Bard or RISD, whose work is in the collections of people with more impressive art addictions, and who has upcoming exhibitions at institutions worth noting."

Each piece carries with it a maker’s process: "This sculpture was dipped in resin, covered with tar, and pissed on." And of course, each piece carries with it intended or interpreted meaning: "This work is about the early childhood development of homosexuals and the myth of latent racism."

We study pedigree, weigh potential, and seek meaning. We self-educate, we inquire. We store this information in the library of our decisions.

Back to our animals. At the moment, our semi-exotic (semiotic?) rabbits are the most perplexing. I am not sure that we can accurately refer to them as pets or farm animals; they don’t want our affection, and they don’t produce anything for our benefit such as eggs or milk. Nonetheless, we recently upgraded their living quarters to an insulated duplex with a private fenced-in yard. Now the rabbits could hop, kick, and jump as much as they pleased.

We imagined they would bask in the sun over a bed of fresh green, nibbling the afternoon away. Instead, they dug an underground tunnel system. By the second day, I couldn’t measure its depths with the extension of my arm and the fresh grass was buried beneath unearthed soil. Their fervor quickly adopted the appearance of an involuntary impulse. They dug and dug and dug, curling around and around and around like a subterranean Spiral Getty.

For a while it seemed that the rabbits wanted desperately to escape (expressing zero gratitude for their updated accommodations). However, they never did. They just kept digging, doing what they do. I thought about the contradiction of their tireless pursuit and their habit of not actually going anywhere. But isn’t there a difference between pursuit and process? One is about the end game and the other is about the here and now. The instinct to dig; the practice of collecting. Perhaps our insatiability is not reflective of something that is unfulfilled, but rather it feeds the process that fulfills us.

Addendum: Since beginning this piece, we gave our aggressive rooster to an artist who ate it, and one of our hens has disappeared. We are down to less.