Buying chickens from Agway is surprisingly competitive. We reserved six Ameracaunas a month before they were due to arrive. For those with a reservation, it’s a first-come, first-served determination of which chicks you get from the 200 that are delivered to the store. For those without a reservation, go home. At $3.25 each, they’re not quite the return that contemporary art promises, though they do produce long-term, consistent gain at breakfast.

By the time we arrived at Agway, the remaining selection of chicks was uninspiring. They were presumably the rejects, and had the least coloration. I never agreed with the popular sentiment that the best works in an exhibition are the ones already sold. However, I had no such clarity in the circumstance at hand.

The chicken guy, Joe, wasn’t as patient and pleasant as usual. He had been dealing with too many reservations and picky decision-makers. Picture an art dealer at day five of an art fair contemplating biting the next person who approaches him. Joe said it really didn’t matter what the chicks looked like two days after being hatched. He said this because he saw me eyeing a reserved chick with a black and white Mohawk, and because he knew that they would change significantly as they developed.

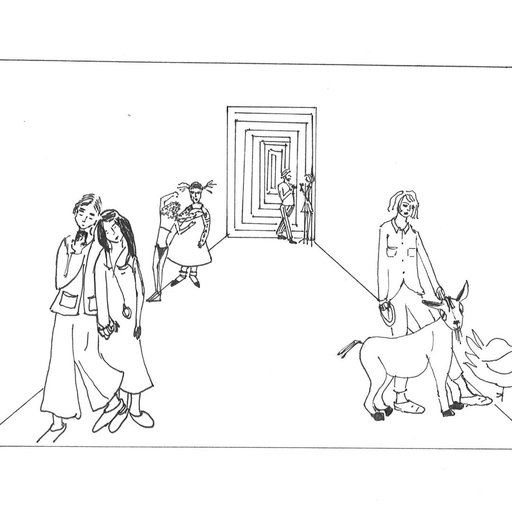

He was right. Our chicks grew into their aesthetic identities, from gold, to black, to black and gold, to white and black, and so on. Of our mandatory minimum of six Agway chicks, no two were the same. I wondered how many combinations of three colors were mathematically possible.

My husband named the chicks during the month he spent building their barn. They spent many days together: Darren observing their unfamiliar, jerky movements, and the hens eying the slow progress of their future estate. A local construction worker saw the fancy coup underway, cocked an eye, and said, “Or, you could just buy eggs.” We stopped feeling stupid by the time they started laying in the fall. No one could have prepared us for the deliciousness of homegrown, free-range eggs.

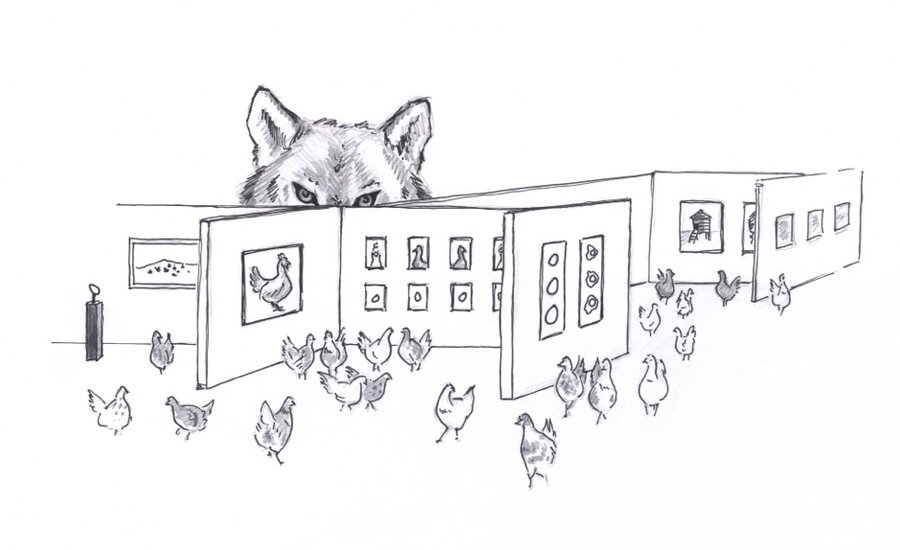

Sadly, of the original Agway Six, only Judy Dench remained. She was the least compelling from the group, but now she had our full attention. The winter had proven to be an inhospitable environment for meat on legs, like the slaughter of small galleries competing against big bad wolves. Chickens have no effective form of self-protection and may as well come with dinner sets strapped to their backs. This is why they stick together, like dealers partnering and galleries merging.

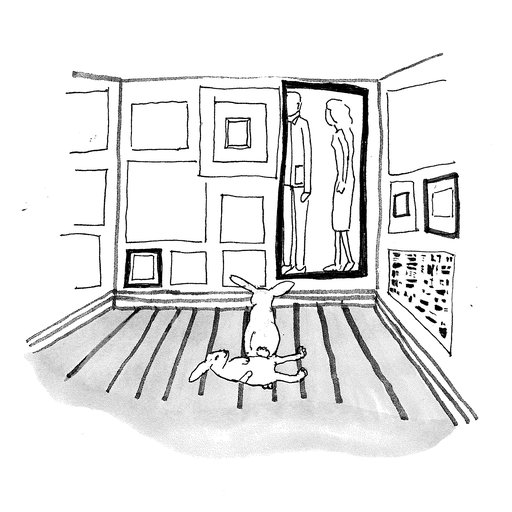

Around the same time we decided to replenish our diminished flock with six new Agway chicks, I decided to open a space in Hudson. Replacing dead chickens with human names was much easier than revisiting the idea of opening another gallery. There were many days when I skirted the possibility, beginning with a free-form year, followed by an emphatic pursuit of anything unrelated, and landing on “the same but different.” My initial looseness was similar to newborn chicks falling asleep, their tiny skulls sunk with the pull of rest, their beaks pulled forward, their necks planted on the ground in an abrupt stupor. This was my “if I can’t see you, you can’t see me” phase, after which I entered the “peck the ground hard at your feet” phase. And finally I arrived to the “I’m going to lay eggs no matter what” phase.

We all experience a gap in life at one time or another. A friend of mine recently hosted a seminal moment in her aging process with friends visiting from far a wide to honor her 30th birthday. Weeks after the hangover faded and the ensuing self-regulated pressure of marking ones life with due meaning and purpose gained shape, she was told by her father that she was, in fact, still 29.

Judging by the speed of their development, I’m not sure that chickens are interested in avoiding or delaying time. However, they do come with built-in social structures most clearly defined by a dominant rooster (think Larry Gagosian micromanaging his team of women directors). But when a flock lacks a rooster, the strongest hen will perform the role. This includes yelling, bullying, and mounting the backs of her sisters (a young Mary Boone?). Initially, the gendered hierarchy pissed me off, but when a hen transitioned into the leadership role everything fell into place. With the rooster gone a hen in place, we were a forward flock.

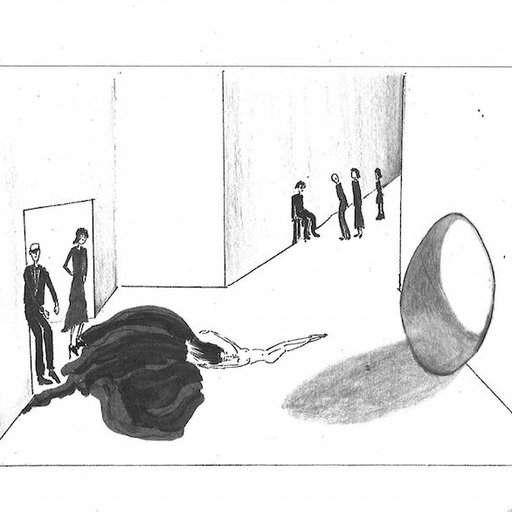

Speaking of the individuality of a bunch of chicks, I have a few questions. When is an artist just an Artist, not a Woman artist, a Black artist, a Queer artist? I think about the commerce of exotifying difference in the contemporary art market. We like it when an artist shows us their world of otherness—black soap and shea butter, perverted scars, the detritus of crumbling buildings. What do we do with a black artist who paints like Pollock? What can we do woman artist whose work is not about being a women?

I think about how women artists are rarely commercially viable, indicating that these descriptors are well in place. If a woman artist were just an Artist, then discrepancies of financial success would not be so glaringly delineated. However, and I am not the first to suggest this, there might be a silver lining to working on the relative fringes of a manic commercial art market. Having spent a significant amount of time recently looking at the range of works and careers of artists who are also women, I see a fertile space of freedom within which to create and from which to support creativity.

Kristen Dodge ran the eponymous DODGEgallery on Rivington Street between 2010 and 2014, when she closed shop and moved with her husband, Darren, to Kinderhook, New York, where they live surrounded by art in a contemporary barn that is itself surrounded by the makings of a small farm. Art vs. Farm is Dodge's column on Artspace chronicling her observations on the intersections of these seemingly polar, living subjects.