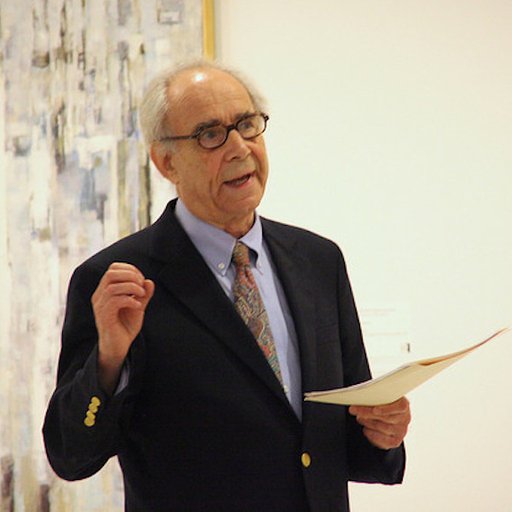

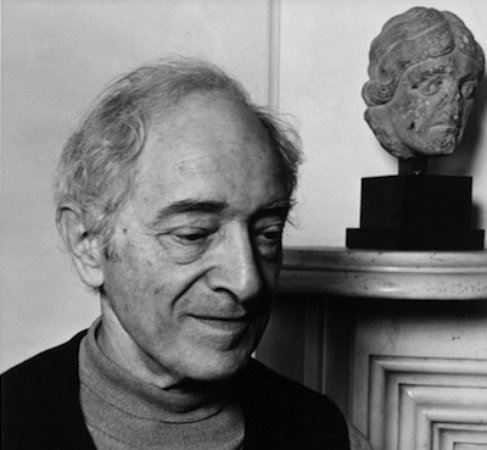

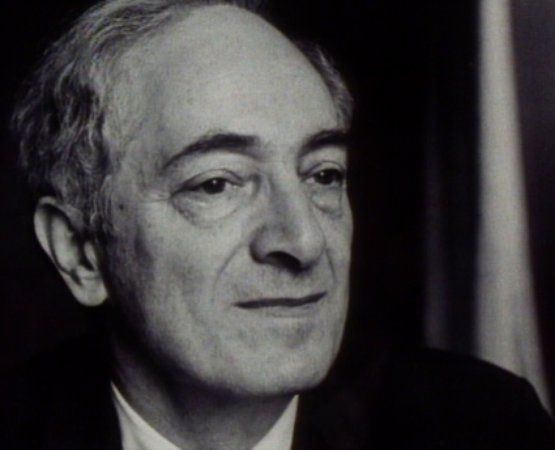

Although Meyer Schapiro (1904-1996) was one of the most influential art historians of the 20th century, his legacy is hard to quantify. He was a professor at Columbia University from 1928 until his death; he also lectured at New York University in the early 1930s and thereafter at the New School. For an academic, Schapiro had a uniquely extensive reach through his lectures, partly because of his involvement with the vital New York art scene of the time, which was beginning to challenge Europe on the field of avant-garde artistic development.

What follows is a brief look into Schapiro’s profound, if elusive, legacy.

WHAT DID HE DO?

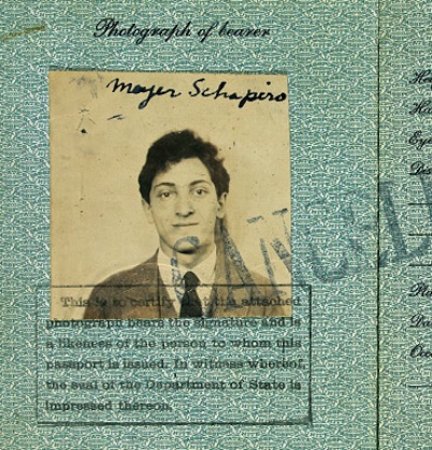

From his arrival at Ellis Island with his family at the age of three, Schapiro was a lifelong New Yorker. His enthusiasm for the city was infectious, and his presence magnetic: he inspired others—the artist and theorist Robert Motherwell was one prominent example—to come to New York.

After completing his doctoral dissertation at Columbia, which revolutionarily taught Romanesque sculpture and mosaics as art, not as artifacts, Schapiro began instructing at his alma mater. His interests ranged from his beloved Medieval sculpture to the art-world goings-on of downtown Manhattan, which Schapiro and his wife, Lillian, energetically kept tabs on, living in the thick of artists and critics in Greenwich Village (at West 4th and West 11th streets, to be precise).

Schapiro was heavily involved in the theoretical—and political—discussions of the day and contributed to, among others, the Marxist Quarterly, the Nation, and the Partisan Review. His critical discourse also went beyond the page to the salon—in the 1930s, Schapiro would organize dinners with his peers, including pioneering MoMA director Alfred Barr, art historian Erwin Panofsky, curator James Johnson Sweeney, art dealer Jerome Klein, and critical and social theorist Lewis Mumford. What was discussed at these gatherings? How much theory was developed, and art analyzed? How much did they drink? A lot.

In addition cultivating a circle of the cultural intelligentsia, Schapiro was a friend and counselor to many artists. He encouraged a doubting Willem de Kooning to continue with his Women series and introduced Fernand Léger to sources that would influence his later work. Schapiro was also instrumental at museums, convincing MoMA to acquire Jackson Pollock’s She-Wolf (1943) in 1944 while Pollock was still a relatively unknown emerging talent.

WHAT EXACTLY WERE SHAPIRO'S IDEAS ABOUT ART?

Like Hegel and Marx, Schapiro believed that art and society were integrated. He didn't believe in separating the understanding of art from an understanding of the societal conditions under which it was made—a practice he admonished Alfred Barr for carrying out at MoMA. In “The Social Bases of Art,” written in 1936, Shapiro asserted that “if we examine the objects a modern artists paints and the psychological attitudes evident in the choice of these objects and their forms, we will see how intimately his art is tied to the life of modern society.”

Even without an object as subject matter, Schapiro believed in society’s interconnection with art. In his 1937 essay “The Nature of Abstract Art,” he responded to Barr’s “one-sided” proposition that “representation is a passive mirroring of things and therefore essentially non-artistic, and that abstract art, on the other hand, is a purely aesthetic activity, unconditioned by objects and based on its own eternal laws.” On the contrary, Schapiro asserted, “there is no ‘pure art,’ unconditioned by experience; all fantasy and formal construction, even the random scribbling of the hand, are shaped by experience and by nonaesthetic concerns.”

For Schapiro, art could not be separated from the artist, and the artist was inextricably linked to his social setting and conditions. In this conviction, Schapiro had more in common with Harold Rosenberg’s assertion of painting as action than with Clement Greenberg’s focus on finished painting’s picture plane.

Their theoretical distinctions aside, Schapiro organized the 1950 exhibition “Talent” with Greenberg at Samuel M. Kootz’s gallery. The show included “new talents” like Franz Kline, Helen Frankenthaler, and Morris Louis. Another foray into curating was Schapiro’s 1957 "Artists of the New York School: The Second Generation at the Jewish Museum," which included 23 artists and sought to map out the contours of Post-Abstract Expressionism.

SHAPIRO'S INFLUENCE

Schapiro’s influence cannot be calculated on the basis of his bibliography or curation. As the English writer and critic John Russell wrote in Schapiro’s New York Times obituary, “his output in print between 1931 and the late 1970s was almost absurdly small in relation to his reputation as both an art historian of the first rank and the most inspiring teacher of his time.” Russell explains that Shapiro was “reluctant to publish” for many years, perhaps because “the printed page ruled out the new insights that came crowding in—or so it seemed—on the spur of the moment and in the heat of exposition.” And, in fact, Schapiro’s improvisatory, almost performative work at the lectern shaped a generation of art historians, as well as the artists who would sit in on his lectures at the New School.

The revolutionary nature and impact of Schapiro’s lectures could not be forgotten. In a 1965 interview with Art News about the catalogue accompanying LACMA’s then-recent show “New York School, First Generation: Paintings of the 1940s and 1950s,” Barnett Newman complained that, “It is impossible to tell from the excerpt quoted from Meyer Schapiro’s talk that it was the first defense made abroad of American painting by an American scholar.” Many of those who fell into his orbit, even domineering presences like Newman, found themselves helplessly becoming his acolytes.

BONUS FACTS

– Schapiro’s writing included essays on artists of the 19th century like Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Georges Seurat, as well as of his contemporaries like Marc Chagall, de Kooning, Motherwell, Pablo Picasso, and Jackson Pollock. On Seurat: “Admirers of Seurat often regret his method, the little dots,” but, Schapiro countered, without these little dots we wouldn't have Seurat’s “surprising image-world where the continuous form is built up from the discrete, and the solid masses emerge from an endless scattering of fine points—a mystery of the coming-into-being for the eye.”

– Schapiro was also an artist himself, though he did not think of himself as more than “summer painter,” according to Lilian, his wife of 68 years. But preparing for a monograph of his artworks later in life, she recalled, Meyer would say, “‘Did I do this?’ and ‘It’s quite good.’”

– He matriculated to Columbia University when he was just 16 after rocketing through high school in Brooklyn.

– He dad a dog named Dada (named by his daughter).

– In 1954 he was co-founder of the political and cultural quarterly Dissent, which is still in publication. (And which inspired the classic line in Annie Hall "Oh really? I had heard that Commentary and Dissent had merged and formed Dysentery.)

MAJOR WORKS

– Romanesque Art (1977)

– Modern Art: 19th and 20th Centuries (1978)

RELATED LINKS

Know Your Critics: What Did Harold Rosenberg Do?

Know Your Critics: What Did Clement Greenberg Do?

Know Your Critics: What Did Leo Steinberg Do?

Know Your Critics: What Did Irving Sandler Do?