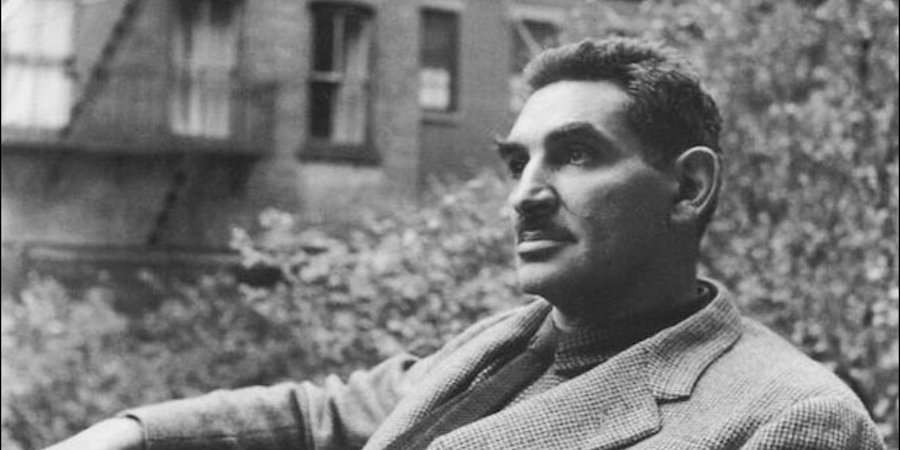

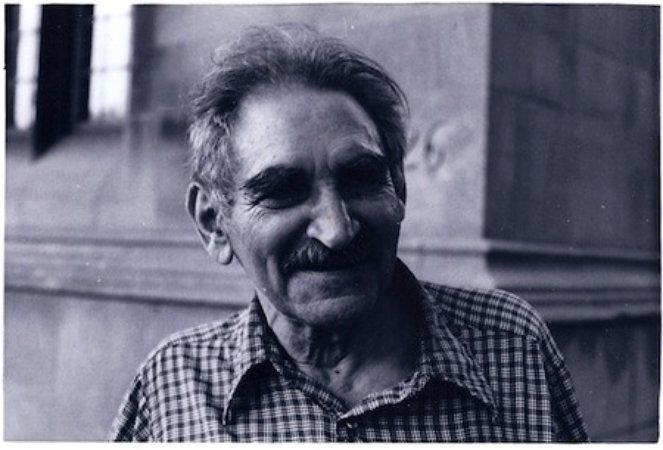

Known for his support of “action painters”—his term for the Abstract Expressionists—Harold Rosenberg (1906-1978) was, along with Clement Greenberg, at the center of mid-century American art criticism. Together, these two critics developed the vocabulary and analytic tools to understand Abstract Expressionism, and to explain its advancements to the rest of the world. There was, however, a catch: they had differing views on why, exactly, this new art was important—and it was in large part their rivalry gave a sense of immediacy to their essays on the new American art. It also pushed them to be exceptionally prolific. Dogged antagonists, they published their essays in combat with one another, and released their anthologies in a syncopation of one-upmanship.

What follows is a rundown of Rosenberg’s theories, as well as how they clash with Greenberg's. Despite their arch-rivalry, it is important to remember they these men were part of a small, tightly-knit community. They saw one another socially—they even sent one another postcards. And it was Rosenberg who introduced Greenberg to the editor of the Partisan Review, the publication for which Greenberg would write his famous essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch.”

WHAT DID HE DO?

Like Clement Greenberg, Rosenberg began his career as a critic writing about politics and culture for small, intellectual, largely Jewish, Marxist-leaning publications like the Partisan Review and Commentary. It was in these magazines, as well as in Art News, that much of their critical debate played out.

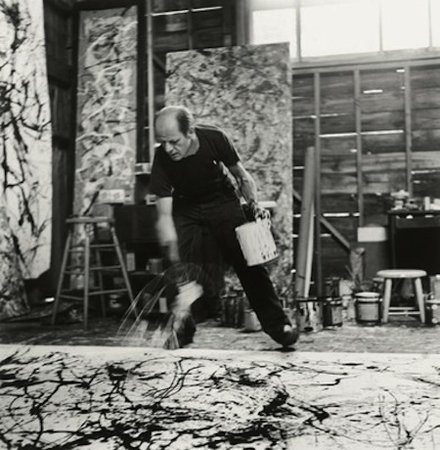

Rosenberg’s major contribution to criticism was his identification of a new breed of “action painting” and his assertion of the “creative act” of the artist, ideas that he potently stated in his 1952 essay “The American Action Painters.” He wrote: “The new American painting is not ‘pure’ art, since the extrusion of the object was not for the sake of the aesthetic. The apples weren’t brushed off the table in order to make room for perfect relations of space and color. They had to do so that nothing would get in the way of the act of painting.” The essay directly countered Clement Greenberg’s focus on the formal and technical aspects of painting (i.e. the “space and color” to which Rosenberg cheekily refers).

For Rosenberg, Abstract Expressionism was not a continuation of modernism, as Greenberg proposed—it was departure. “With the American, heir of the pioneer and the immigrant, the foundering of Art and Society was not experienced as a loss," he wrote. "On the contrary, the end of Art marked the beginning of an optimism regarding himself as an artist.” For artists, Rosenberg argued, freedom lay in the act of creating art itself: “The big moment came when it was decided to paint... just to PAINT. The gesture on the canvas was a gesture of liberation, from Value—political, aesthetic, moral.”

Moreover, if art was about doing, then “a painting that is an act is inseparable from the biography of an artist,” he wrote. This directly countered Greenberg’s rejection of the biography in favor of analyzing the object. Rosenberg’s focus on action and the individual found a natural extension in his belief in the existential qualities of the new American painting, for “the act on the canvas springs from an attempt to resurrect the saving moment in his ‘story’ when the painter first felt himself released from Value—myth of the past self-recognition.”

Like Greenberg, Rosenberg’s theories applied almost exclusively to painting. Rosenberg reasoned that “Only the blank canvas... offered the opportunity for a doing that would not be seized.... Painting became the means of confronting in daily practice the problematic nature of modern individuality. In this way Action Painting restored a metaphysical point to art.” For Rosenberg, the existential held a central place in painting; for his arch-rival, however, the focus resided on painting’s surface, in its formal qualities.

Along with writing, Rosenberg curated on occasion. He notably co-organized a show of the Abstract Expressionists called "The Intrasubjectives" with Samuel M. Kootz at Kootz’s gallery in 1949. The show included: de Kooning, Wiliam Baziotes, Arshile Gorky, Adolph Gottlieb, Morris Graves, Hans Hofmann, Motherwell, Pollock, Ad Reinhardt, Rothko, Mark Tobey, and Bradley Walker Tomlin. Kootz selected the roster and show’s title (which came from Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset) but the exhibition’s artists and philosophic nods to subjectivity remained at the core of Rosenberg’s work thereafter, and were therefore synonymous with his byline.

While Rosenberg’s theories did not experience the same backlash as Greenberg’s, Rosenberg did not embrace the next wave of artistic movements like Pop or Minimalism. Rosenberg continued to publish and write for The New Yorker until his death in 1978; his last works included a book on Barnett Newman and an Whitney Museum retrospective of his colleague at The New Yorker, Saul Steinberg.

BONUS FACTS

– Lee Krasner, Pollock's wife, briefly lived with Rosenberg and his wife, May Tabak, in the 1930s.

– He started a short-lived magazine with Robert Motherwell called Possibilities (1947-48).

– Rosenberg played pitcher in the famous 1954 art-world baseball game in East Hampton, and his team—which included Willem and Elaine de Kooning as well as Franz Kline—decided to play a joke on the other team’s star hitter, the artist Philip Pavia. As fabled Art News editor Thomas Hess recounted, the night before the game Kline and the de Koonings “bought two grapefruit and a coconut. They worked until two in the morning sandpapering them and painting them to look exactly like softballs, with all the essential seams, cracks, chiaroscuro, and even a trade label, ‘Pavia Sports Association.’ The next day, when the game was about halfway over, Harold Rosenberg came up to pitch. Pavia was at bat. Rosenberg pitched the first ball. Pavia swung, and it exploded in a great ball of grapefruit juice.”

– Rosenberg had an affair with Elaine de Kooning. Tongues would wag that Willem de Kooning’s painting got very good reviews from Rosenberg as a result.

– Rosenberg, Elaine de Kooning, and Thomas Hess were a regular trio at the Cedar Tavern, the Greenwich Village watering hole and think tank of many Abstract Expressionist. The three made a pact that any one of them was allowed to quote the other two—even if the quote was bogus—if it would win an argument outside of their trio.

– Elaine de Kooning was effusive, if slightly reserved, about Rosenberg’s abilities: “He was brilliant, just brilliant. He was a man of ideas. He was profoundly intelligent, and very funny. I mean, he knew almost everything. Everything except how to look at a painting. He would stand in front of a painting—Bill’s [Willem de Kooning] painting, Franz’s [Kline] painting, anybody’s painting—and talk about great ideas.... But it didn’t matter because he wrote those brilliant articles which made nothing absolutely clear and made everything about art totally fascinating.”

– Even Greenberg appreciated Rosenberg’s illuminations (on occasion). As “Clem” wrote to his friend Harold Lazarus, “Rosenberg’s piece [“On the Fall of Paris”] was badly & dishonestly written & yet was good. Good in spite of the things that made me grit my teeth, in spite of the rotten pretentiousness that came through and the utter lack of feeling for the language” (January 6, 1941).

– Rosenberg had wanted to be a tango dancer but couldn’t pursue it after an illness left him with a bad leg.

MAJOR WORKS

– “On the Fall of Paris” (Partisan Review,1940)

– “The American Action Painters” (Art News, 1952)

– The Tradition of the New (1959)

– The Anxious Object (1964)

– The De-Definition of Art: Action Art to Pop to Earthworks (1972)

– Art on the Edge: Creators and Situations (1975)

RELATED LINKS

Know Your Critics: What Did Clement Greenberg Do?

Know Your Critics: What Did Leo Steinberg Do?

Know Your Critics: What Did Meyer Schapiro Do?

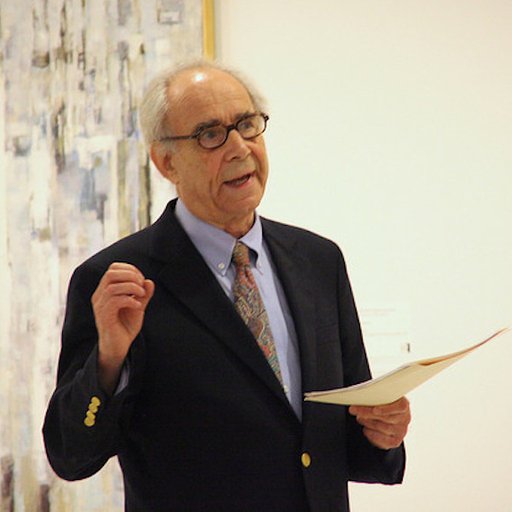

Know Your Critics: What Did Irving Sandler Do?