Your Nan Goldin print is framed and hung in the perfect spot, and now your friends and neighbors are coming over to admire the work. It’s a great talking point, but have you got all the answers? Do you know which shows helped establish her career? Which President blamed her for heroin chic? Which other artists feature in her pictures? And which protest cause has catapulted her back into the headlines? Don’t worry, you’ll have all the answers after reading this.

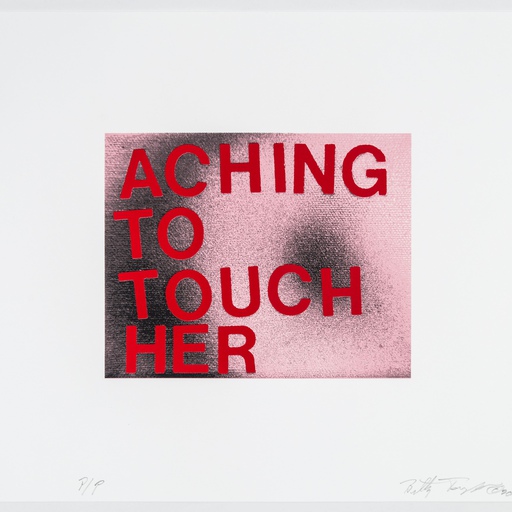

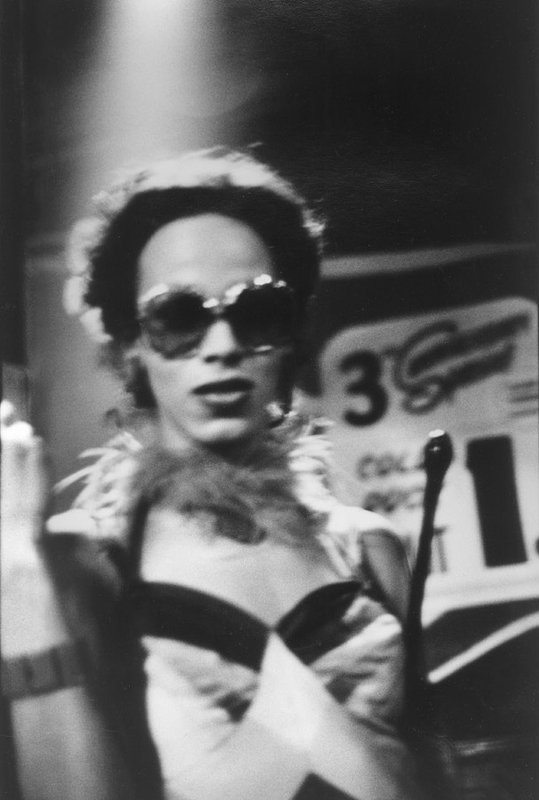

Bea with a whip at The Other Side

, 1973, by Nan Goldin

Bea with a whip at The Other Side

, 1973, by Nan Goldin

So, I know the name, but remind me again?

Nan Goldin is a 66-year-old, US photographer, best known for her candid, diary-like depictions of beautiful outsiders. Beginning in her hometown of Boston, she photographed her friends in the city’s gay and transvestite communities, before going on to shoot the inhabitants of New York’s Lower East Side. Her best-known work, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – a slideshow of images, set to the music of the Velvet Underground, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Maria Callas, and Nina Simone among others – began as entertainment for friends, but was included in the 1985 Whitney Biennial, to great acclaim. Eight years later, her inclusion in the 1993 Whitney Biennial truly established Goldin's place in contemporary American art. Since then she has lived and worked across the world, and become one of the most recognisable, satisfying, and bankable photographers active today. Indeed, her prices have risen pretty steeply over recent years. Goldin’s 1995 portfolio of photographs of the model James King sold for £22,500 at Phillips in London back in May 2019, while her 1999 photograph, Skyline from my window, NY, went for $21,250 at Phillips in New York, back in October 2018.

Jimmy Paulette on David's bicycle,

1991, by Nan Goldin

Jimmy Paulette on David's bicycle,

1991, by Nan Goldin

What key events ‘made’ her? And who has she influenced?

Goldin had a challenging start to life. Her sister’s suicide, which occurred when Nan was just 11, was a formative experience – but she still went on to study at the noted photography school Imageworks in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts/Tufts University in Boston, where she drew upon the work of August Sander, Larry Clark and Diane Arbus . Goldin has also acknowledged the influence of the Swedish street photographer, Christer Strömholm, and the early color-photography pioneers Stephen Shore and William Eggleston . In terms of her own influence, Goldin’s style and sympathies can be detected in the work of a wide range of younger photographers, including Ryan McGinley , Terry Richardson and the late Ren Hang. However, rather than view Goldin purely through the prism of photography, it might be better to look towards wider cultural trends occurring in the late 20 th century.

“The circumstances and inseparability of Goldin’s art and life mark her as an important witness to a generation that was undergoing a political withdrawal from the American establishment,” writes the curator Catherine Lampert in Goldin’s 2003 monograph, The Devil’s Playground . “These post-war children from various backgrounds turned away from national values, and adopted a position of permanent marginality.” In this sense, we can see her work completing that of Raymond Pettibon , Jean-Michel Basquiat , Robert Mapplethorpe and Andy Warhol . Yet her auction prices remain below her male peers, at least for the time being.

Cookie and Millie in the Girls' Bathroom at the Mudd Club, NYC

, 1979, by Nan Goldin

Cookie and Millie in the Girls' Bathroom at the Mudd Club, NYC

, 1979, by Nan Goldin

Who are all these people in her pictures?

Some of them are well-known artists in their own right, such as the painter, writer and filmmaker David Wojnarocwiz , the painter and sculptor Kathleen White , the poet and actor Rene Ricard, and the singer Lydia Lunch. Others are better known to us via Goldin’s photographs. Look out for recurrent appearances from the actor and writer Cookie Mueller, and the Italian gallerist Guido Costa, and Goldin’s long-time friend and fellow photographer, David Armstrong . Some occupy an intermediary space; German actor Clemens Schick appears in many of Goldin’s later pictures, but you may have also seen him play a Bond baddie in the 2006 movie Casino Royale .

They’re all so intriguing, and it’s tempting to fill in as much biographical detail as possible, but perhaps some of the pleasure of viewing Goldin’s photographs lies in not knowing everything about these strange, glamorous figures. As Michael Kimmelman wrote in the New York Times, in response to Goldin’s 1996 Whitney Museum retrospective: “She makes you believe you know these strangers because she reveals something intimate about them, something we probably wouldn't want revealed about ourselves, and this leaves them exposed, touchingly so.”

Jens' hand on Clemens' back, Paris

, 2001, by Nan Goldin

Jens' hand on Clemens' back, Paris

, 2001, by Nan Goldin

Should we view her as a documentary photographer, or is there something else going on here?

While there’s no denying Goldin’s shots of drag queens, junkies and struggling artists tell us something about big city life, there’s something a little more personal and tender going on in her pictures that goes beyond a simple visual record. As Goldin once put it, “for me, it’s not a detachment to take a picture. It’s a way of touching somebody – it’s a caress.”

Simon on the Subway, NYC,

1998, by Nan Goldin

Simon on the Subway, NYC,

1998, by Nan Goldin

Did Bill Clinton really get her name wrong?

Possibly. In 1997, at the height of the hysteria surrounding ‘heroin chic’, Goldin recalls watching an address from President Clinton while riding an exercise bike at a gym. The sound was turned down on the gym TV, so she only read the caption, which said that Clinton ‘'blames Dan Goldin for heroin chic.’ It may have been a gender-bending mistake on the President’s part, or the TV caption technician could have mistyped her name.

Valerie floating

, 2001, by Nan Goldin

Valerie floating

, 2001, by Nan Goldin

Boring question, but does she shoot on film or has she gone digital?

Actually, it’s a central concern for Goldin. She remains a passionate defender of film over digital photography, and has said that she would refuse to have her portrait taken on a digital camera. Recently, she’s likened the difference between digital photography and film to cultured and naturally formed pearls. “You take a thousand pictures to get a good one, like oysters with the rare pearl,” she told Vogue in 2015. “It’s a lot to do with generosity, just taking thousands and thousands of pictures, and then where the art comes in is the editing.”

Aperture Drugs on the Rug, New York City, USA

, 2016, by Nan Goldin

Aperture Drugs on the Rug, New York City, USA

, 2016, by Nan Goldin

Haven't I seen her in the news recently?

Yes, her recent activism has made headlines way beyond the artworld. In 2017 Goldin founded the campaign organisation P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), to draw attention to art-world philanthropists, the Sackler Family, and the income they have derived from Oxycontin, the drug at the heart of America’s opioid crisis. Goldin and her fellow activists staged a high-profile ‘die-in’ protest at the Guggenheim Museum in February 2019, before going on to lead a protest outside the Louvre in Paris in July 2019, and at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in November 2019. In each instance Goldin – who was a heroin user during the 1970s and ‘80s, before succumbing to opioid addiction from 2014 until 2017 – called for the institutions to end their relationships with the Sacklers. Many complied, and the photographs of the protests have found an appreciative audience too. Time magazine chose an image from Goldin’s Guggenheim die-in as one of its 100 top photos of 2019.

Self-portrait, laughing, Paris,

1999 by Nan Goldin

Self-portrait, laughing, Paris,

1999 by Nan Goldin

What can I hang her work next to?

Her pictures work well next to the punky works of Raymond Pettibon , the highly sexualised pictures of Allen Jones , and the more ascetic, though no less powerfully erotic prints of Robert Mapplethorpe . She also hangs perfectly alongside fellow titans of post-punk New York, such as Jenny Holzer , Robert Longo , Barbara Kruger , Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring . Yet don’t forget about her place alongside other great, contemporary female artists, such as Cecily Brown , Celia Hempton and Jenny Saville , or great American photographers such as Joel Meyerowitz , Stephen Shore , and Weegee .