As we detailed last month, New York’s Museum of Modern Art has released their full exhibition archives for free online—a veritable treasure trove of photo documentation, show catalogs, press releases, and more. An art-history aficionado can easily lose hours browsing the institution’s more than 3,500-odd exhibitions (this author already has), and the archive is positively teeming with tasty historical morsels of the sort usually only available in graduate courses.

Chances are very good that your favorite artists from the past hundred years have been featured at one time or another, so you might want to check it out for yourself. In the meantime, we’re delved into the e-archive ourselves to find the most interesting exhibitions from years past, focusing on both epoch-making surveys as well as quirkier offerings that illustrate the continuously experimental nature of the museum’s programming.

Following our exploration of the museum’s first decade (the 1930s), we’re skipping forward to the strange and swinging 1960s. Let's set the scene. World War II had come and gone, as had the prosperous and conformist ‘50s. The nation was gearing up for what would prove to be one of the most tumultuous periods of its young life, a moment of widespread cultural, political, and artistic upheaval in the U.S. and abroad that saw both the rise of the civil rights movement and the start of the Vietnam War.

At the same time, many of today’s canonical artists were just beginning to fully unfurl their talents, buoyed in no small part by their inclusion in these seven seminal MoMA exhibitions. Read on for a little art-historical desktop time travel.

"16 Americans"

December 16, 1959–February 17, 1960

Over the years, certain MoMA shows have become the stuff of art history, perennially referenced for their impact on the movements or artists they brought to the fore. Dorothy Canning Miller’s widely influential “16 Americans” is one of these shows, credited with introducing the work of such giants as Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Louise Nevelson, Robert Rauschenberg, and Frank Stella to a wider audience at the early stages of their careers.

Though these artists may have been familiar to art-world circles, this show served as a kind springboard for their eventual acceptance as heirs to the already-waning popularity of the 1950s Abstract Expressionists. Perhaps more interesting to buffs of contemporary art history are the other Americans included in the show who did not achieve the renown of their fellows, including Landés Lewitten and Alfred Leslie.

"Homage to New York: A Self-Constructing and Self-Destroying Work of Art Conceived and Built by Jean Tinguely"

March 17, 1960

More an event than an exhibition, the subtitle for the Swiss artist’s most famous work says it all. Over the course of a single half hour, viewers assembled in MoMA’s sculpture garden looked on as Tinguely’s complexly jury-rigged, teetering, literally explosive structure chugged, shuddered, and detonated itself to death. (Though not entirely—Billy Klüver, the famed Bell Labs engineer who helped Tinguely assemble the work, reported that the machine did not completely disintegrate as planned.) Nevertheless, the event has become nothing short of legendary in the realm of kinetic art, creating a nice metaphor for the failures of mechanized Modernism that were, in the spring of 1960, just beginning to be reckoned with by a new generation of artists.

"The Art of Assemblage"

October 4–November 12, 1961

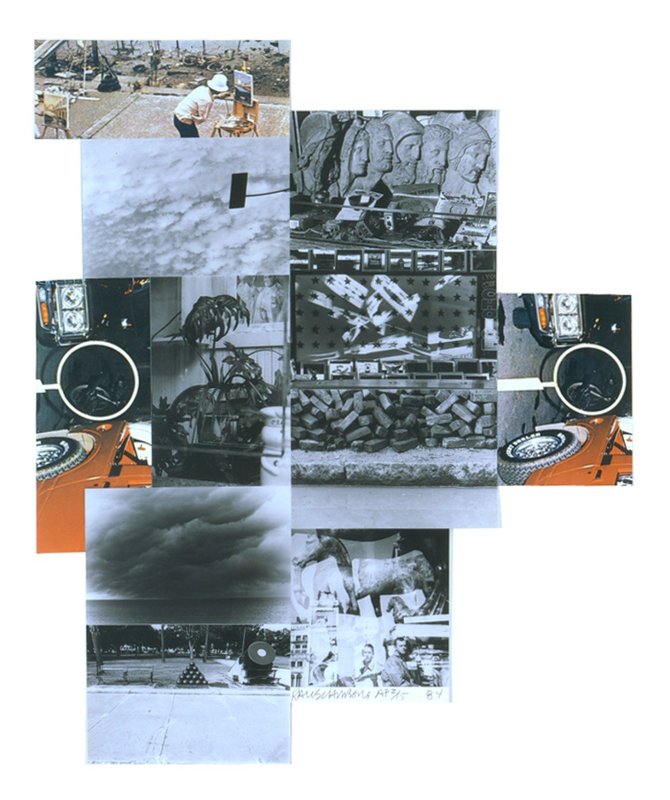

Assemblage has been part of the Modern-art toolkit ever since Picasso’scubist constructions of the early 1910s, and artists from Jean Dubuffet to Louise Nevelson took up the technique in earnest throughout the subsequent decades. By the time the 1960s rolled around, these works had become central to the story of 20th-century art—to the extent that the exhibition’s curator, William C. Seitz, could write in the catalog that “collage and related modes of construction manifest a predisposition that is characteristically modern” insofar as they “denote not only a specific technical procedure and form used in the literary and musical as well as the plastic arts, but also a complex of attitudes and ideas.”

The show aimed to be exhaustive, featuring 250 works by 130 artists from the U.S. and Europe, including longtime MoMA favorites Picasso, Duchamp, and de Kooning, an entire room devoted to Kurt Schwitters, works by the already-acclaimed New York darlings Robert Rauschenberg and Joseph Cornell, and contributions from “foreign” and relatively unknown West Coasters including Bruce Conner and Edward Kienholz.

"Architecture Without Architects"

November 11, 1964–February 7, 1965

MoMA’s early history is marked by an ongoing interest in celebrating forms and techniques not usually considered in the context of fine art—perhaps the outgrowth of its habitual revolt against the strictures of good taste as the museum worked to legitimize “ugly” and “nonsensical” Modern art in the 1930s. The happy result is a number of shows focusing on vernacular or amateur works, including this exhibition of what could be called “outsider architecture” organized by the eccentric architect and designer Bernard Rudofsky, author of such memorable tomes as 1947’s Are Clothes Modern?

With reference points ranging from Sudanese cliff dwellings and Native American amphitheaters to classical Greek forms to the mobile structures of nomadic and seafaring groups, Rudofsky’s stated goal was to “break down our narrow concepts of the art of building by introducing the unfamiliar world of nonpedigreed architecture”—a notable early instance of non-Eurocentric thinking in the American art establishment.

"The Responsive Eye"

February 23–April 25, 1965

You can’t get far in a serious discussion of Op Art without eventually referring to “The Responsive Eye,” another of Seitz’s vital contributions the artistic climate of the 1960s. All big names from the short-lived style are here, including Bridget Riley, Victor Vasarely, and Richard Anuszkiewicz, in addition to figures like Stella and Ad Reinhardt who not often associated with the movement. The show proved to be a smash hit with the New York art audience, drawing more than 180,000 visitors. Art critics, however, reacted strongly against what they saw as simple visual trickery, relegating Op Art to the realm of commercial imagery and as a result inadvertently writing off one of the most recognizable motifs of the still-nascent Psychedelic Sixties.

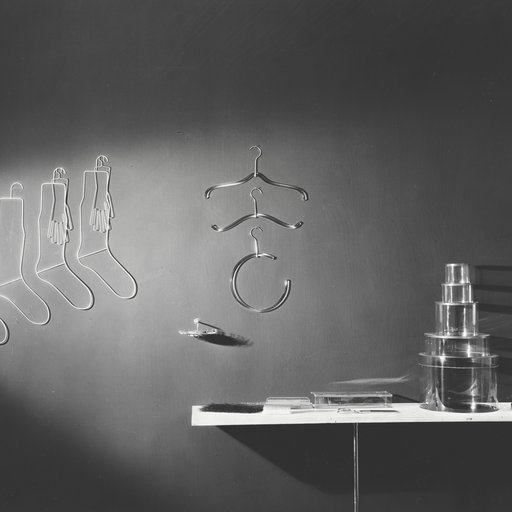

"Once Invisible"

June 20–September 11, 1967

Combining MoMA’s longstanding efforts to champion the photograph as a revolutionary fine art of the 20th century and the institution's interest in including supposedly non-art practices within the context of the museum, “Once Invisible” focused on images that, as the press release states, “exist in the world but cannot be seen by the human eye without the aid of photography.”

The museum’s fabled photography curator John Szarkowski organized the show into three sections: “Analysis and Synthesis of Time,” featuring stop-motion techniques that included Eadweard Muybridge’s seminal series of horses and men caught mid-stride; “Invisible Energy Sources” capturing visualizations of such ethereal phenomena as a wood-thrush song, infrared heat, and electron emissions; and “Vantage Points,” which includes both NASA-sourced images from space (a year before the release of the famous “Moonrise” photograph from the Apollo 8 mission) as well as scenes from inside a blast furnace.

With their emphasis on process and an embrace of cutting-edge tech, many of these works could conformably fit into a present-day show of conceptual art—and it's interesting that MoMA chose to hang this show just as capital-c Conceptualism was coming into vogue. (Sol LeWitt’s potent “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” was published in the June 1967 issue of Artform, nearly concurrently with the opening of this show.)

"In Honor of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr."

October 31–November 3, 1968

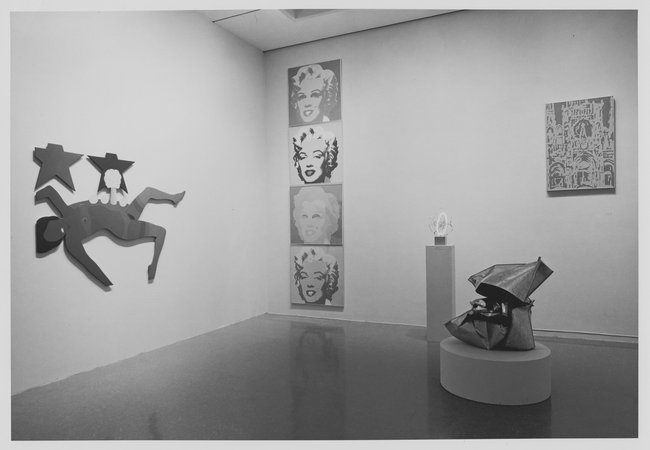

Though MoMA occasionally flirted with politically motivated topics during its first several decades—including exhibitions of artworks made through the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration in the ‘30s and several shows in support of the military during World War II—the institution, like most of its cohorts then and now, tended to keep the focus on art rather than current events. One notable exception, however, was “In Honor of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.,” organized in the months after King’s assassination in April 1968.

The exhibition included pieces donated by some 60 American artists, all intended to be sold in support of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the civil rights group founded by King in 1957 following the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. This show was one of the first instances of the museum holding a benefit for another organization, and they pulled out all the stops: Jackie Kennedy served as an honorary patron, and the donated works included pieces by Andy Warhol, Romare Bearden, Donald Judd, Isamu Noguchi, and many more.