"Your work is very organic," an interviewer famously opined to Barbara Hepworth in the early 1970s. "It’s meant to be. I’m organic myself!" was the British sculptor’s succinct, though revealing, reply.

The subject of "Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World," a career retrospective at Tate Britain (through October 25), Hepworth (1903-1975) has often been characterized as an artist who was totally in tune with herself and with nature. Her sculptures evoke the play of wind and air, sunlight and sea spray on the Cornish coast, and seem imbued with an inner calmness and strength.

The Tate show conveys these aspects of Hepworth's art, but also makes an effort to place her in the wider context of international modernism. Some reviewers have commented on Hepworth's relatively lowly international standing and observed that her early work looks derivative when exhibited alongside pieces by her forebears and contemporaries, as it is in the first gallery of the Tate show. Few have noted however, that she played a huge part in breaking down the walls of a male-dominated art establishment.

We come to see Hepworth as an artist who was very much aware of these obstacles and worked steadily to chip away at them, even as she kept time with her own heartbeat or the sound of sea waves breaking on the shore near her Cornwall cottage. Here are five works that chart her artistic journey.

DOVES (GROUP), 1927

Doves (Group), 1927. Sculpture, Parian marble. Manchester Art Gallery, ©Bowness, Hepworth Estate.

Doves (Group), 1927. Sculpture, Parian marble. Manchester Art Gallery, ©Bowness, Hepworth Estate.

One of Hepworth’s earliest surviving works, Doves was made in Italy shortly after the artist met her first husband, John Skeaping. The pair did keep doves, although this piece was inspired by Jacob Epstein’s more sexually-charged marble sculptures of conjoined doves. It was the first example of what would turn out to be, for Hepworth, a lifelong motif: two forms related to each other in a sympathetic relationship. Distancing herself from the outmoded Victorian fashion of clay modeling and casting herself as a new breed of "carver," Hepworth deliberately left the base of the sculpture rough-hewn.

THREE FORMS (1935)

Three Forms,1935. Sculpture, Serravezza marble on marble base. Tate © Bowness, Hepworth Estate.

Three Forms,1935. Sculpture, Serravezza marble on marble base. Tate © Bowness, Hepworth Estate.

Returning to England with Skeaping in 1927, Hepworth set up home in Hampstead. Here, in a tiny basement apartment in 1934, she gave birth to triplets—“a tremendously exciting event,” as she described it. “We were only prepared for one child and the arrival of three babies by six o’clock in the morning meant considerable improvisation for the first few days.” When she began carving again toward the end of the year, her work started to move in a new direction—an exploration of the tensions between forms, and an attempt to define the absolute essence of human relationships.

PENDOUR (1947)

Pendour, 1947. Painted plane wood. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, USA. © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Pendour, 1947. Painted plane wood. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, USA. © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Now living in St. Ives, in the south of England, Hepworth began to introduce the color of the drawings she had made during the war years into her woodcarvings. She found the wood she used during long walks along the beach. Pendour Cove, the setting for a myth in which a man is enchanted by a mermaid and beckons her from the sea by singing, was a regular stop on her way. Conceived as she lay on the beach looking at the sky, Pendour was among the first works in which Hepworth attempted to imbue herself with landscape rather than merely inhabit it.

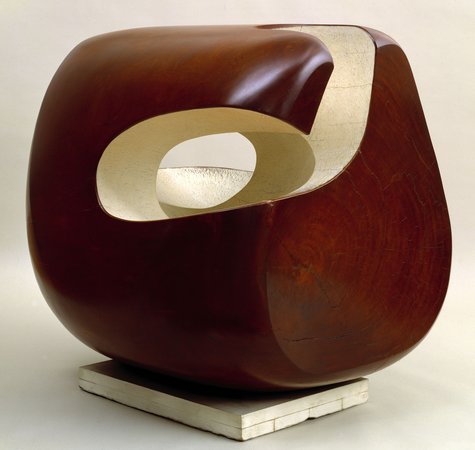

CORINTHOS (1954-5)

Corinthos, 1954-5. Sculpture, Guarea wood and paint on wooden base. Tate © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Corinthos, 1954-5. Sculpture, Guarea wood and paint on wooden base. Tate © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Separated from second husband, Ben Nicholson, and grieving over the death of her son Paul in a plane crash the previous year, Hepworth took a restorative trip to Greece to look at classical sculpture and carving. Newly inspired, she imported huge quantities of African hardwood to St Ives and used it to carve five pieces, of which Corinthos is one. “Already one of the largest logs is taking shape,” she wrote in a letter to a friend during its creation. Of its cavernous appearance she noted: “A great cave is appearing and I have tunneled right through. Daylight gleams within it.”

FALLEN IMAGES (1974-75)

Fallen Images, 1974-75. Sculpture, marble on constructed wood base. Tate © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Hepworth made a number of white marble carvings in her final years, returning to the classical material she had learned to work with in Italy in the 1920s. (Hepworth claimed in a letter to a friend she was one of the few people in the world who knew “how to speak through marble.”) This was her last sculpture, completed shortly before she died in a fire at her cottage (her evening habit of sleeping pill and cigarette proving fatal). It has been suggested that the two truncated cones are standing figures—a man and a woman. Certainly, they resemble the Neolithic stone-like forms hinted at in her 1935 work, Three Forms (above). The tenor and the title of the work has led some to believe that Hepworth, afflicted by now with tongue and throat cancer, was seeking the serenity and calm of her mid-1930s abstract carvings.