Best known for her “plastic portraits” of dolls and dollhouses, the photographer Laurie Simmons has been making psychologically probing tableaux since moving to New York as a young artist in the late 1970s. It was there that she found her artistic home, associating with a group of artists—including Cindy Sherman , Barbara Kruger , and Sherrie Levine — who became known as “ the Pictures Generation ” for their habit of appropriating images from advertising and popular media and questioning their embedded assumptions about desire and happiness.

From the beginning Simmons found an eerily compelling interiority in inanimate objects, placing predominantly female dolls in domestic environments and photographing them in poses that evince fraught emotions. With each subsequent series, she has tested the limits of our ability to empathize with her subjects (whether they are manufactured or human). A subtle yet potent feminism pervades her work: the viewer is encouraged to see these female figures in their conventional contexts, and at the same time is rebuked for it.

This month, the Jewish Museum is presenting " How We See ," a show of new work by the artist that represents a key shift from her earlier efforts. Here her subjects are real people, not dolls. (There is a catch, however, as you will see.) To mark the opening of the exhibition, here is a primer on the arc of Simmons career.

DOLLS & DOLL HOUSES  Purple Woman/Gray Chair/Green Rug (1978)

Purple Woman/Gray Chair/Green Rug (1978)

Simmons's earliest and best-known series, the seminal "Early Color Interiors" of 1978-9, features closely cropped photos of the decór, accessories, and plasticine denizens of doll houses. Capturing these figures in moments of reflection or desperation against often stridently patterned trimmings, the pictures display a mastery of framing and composition that owes as much to advertising imagery and Hollywood as it does to fine-art photography. As she continued her work with plastic figurines Simmons began to put more emphasis on the backgrounds, often making her own from ‘50s fashion and design magazine clippings.

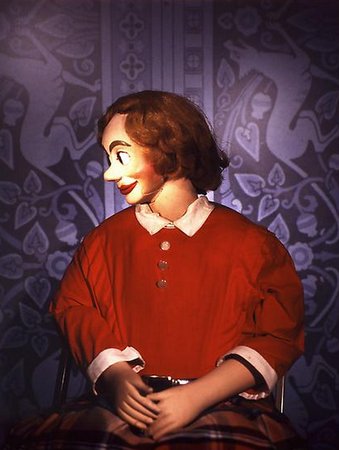

VENTRILOQUIST DUMMIES  Jane (1988)

Jane (1988)

After making several series of doll photographs, Simmons turned her attention to ventriloquist dummies and other "Talking Objects"—as she titled one 1987-89 series—of the sort used in voice-throwing stage shows. Together with the "Actual Photos" series from 1985, these stand as the first examples of traditional portrait photography in her work, insofar as they focus on a central, frontally-oriented human or semi-human figure. Once again the ornate background details and settings are emphasized, although here they evoke Renaissance portraits (including the paintings of Bronzino.)

" WALKING AND LYING OBJECTS" (1987-1991)  Walking Hourglass (Color) , 1989

Walking Hourglass (Color) , 1989

Around the same time she first photographed her ventriloquist dummies, Simmons also began to experiment with a new kind of figure: a hybrid one, made of human legs in combination with books, cakes, guns, or other objects. The artist has said that the impetus for these "Walking and Lying Objects" was a photograph that she took of her friend, the artist Jimmy DeSana, while he was wearing a giant prop camera from the musical Wiz over his head and torso. Although the other images in the series—which was recently rebooted for a booth at the 2014 ADAA Art Fair—are largely miniatures as opposed to staged human subjects like DeSana, this body of work nevertheless brought Simmons closer to using the living body in her work.

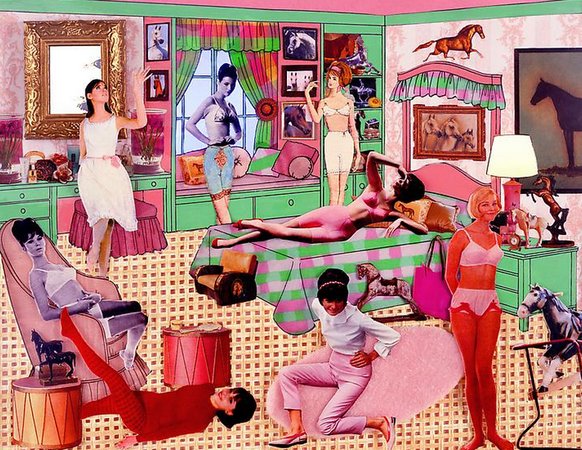

"INSTANT DECORATOR" (2001-2004)  The Instant Decorator (Pink and Green Bedroom/ Slumber Party) , 2004

The Instant Decorator (Pink and Green Bedroom/ Slumber Party) , 2004

If her "Walking Object" photos deemphasized mise-en-scène to focus on the objects themselves, the collaged scenes of "Instant Decorator" reversed the process; they used cutouts of fashion models and dollhouse-like settings in boisterous tableaux. While the older pictures play with lighting and perspective to make it difficult to discern which parts of the scene exist in three dimensions, these collages are evidently flat with perspective conveyed by the size of the cutout images.

THE LOVE DOLL (2009-2011)  The Love Doll/Day 24 (Diving) (2010)

The Love Doll/Day 24 (Diving) (2010)

In this series, Simmons trades her child-friendly dolls for a decidedly more adult version—a single life-size Japanese sex doll, which she photographed in her own Connecticut home. Capturing this protagonist's journey from shipping container to live-at-home geisha, the body of work culminates with the doll—whose glistening eyes and supple fingers convey a startling verisimilitude—hopping a stone wall, perhaps escaping into a new life.

"KIGURUMI, DOLLERS, AND HOW WE SEE" (2014)  Orange Hair/Snow/Close Up , 2014

Orange Hair/Snow/Close Up , 2014

This series, which debuting in Simmons's 2014 exhibition at Salon 94, flips the script on the sex doll. It delves into Japan's "doller" subculture to depict live humans who dress in full-body anime-doll costumes (complete with latex gloves and masks with oversized, dewy eyes.) These are people at a remove—as unreadable, in their way, as the figurines that inhabit the dollhouses of her earliest series.

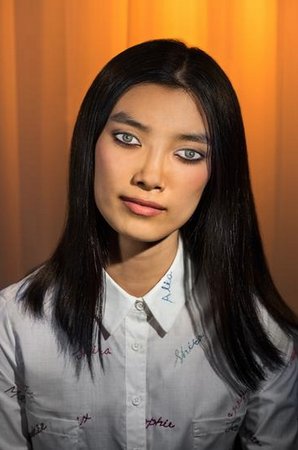

"HOW WE SEE" (2015)  How We See/Sisi (Gold) , 2015

How We See/Sisi (Gold) , 2015

Even more uncanny are the "How We See" photos, the recent works in the Jewish Museum exhibition, which pick up on a subset of the previous series "Kigurumi, Dollers, and How We See." These portraits transform from banal, fashion-y portraits into unsettling ciphers as one realizes that the women's eyes are painted onto their closed lids. In this body of work, Simmons manages to come full circle: whereas she began by investing inanimate objects with an interior life, here she transforms real people into subjects as listlessly vacant as any doll.