When John Baldessari started creating his text paintings in the mid 1960s, only a handful of artists had ever trifled with the idea. There were Roy Lichtenstein's paintings from comics, and the Cubists had integrated newspaper clippings in their work, but nobody had been brave enough to exhibit paintings that simply offered text.

For one of his early text paintings, Baldessari chose a simple phrase that offered a perfect example of the layered meanings his work is often able to express with extremely limited means: "Pure Beauty." Presented against a stark, dully monochrome background, the piece was a challenge to viewers who hoped to find painterly drama on the canvas—and, simultaneously, it was a critique of those Minimalists who at the time were stripping all the fun out of art. Either way, Baldessari put himself at the center of the debate about what qualified as art, and quickly gained a reputation for intelligent work that was at once controversial, quirky, humorous, and groundbreaking.

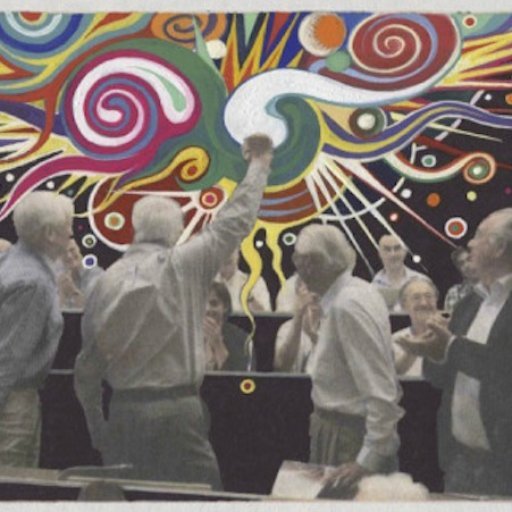

Today, Baldessari is considered one of the fathers of Conceptual art—not only for the influence of his art, but also for his four decades as a leading instructor at CalArts and UCLA—and he remains one of the most well-respected artists alive. He was awarded the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale in 2009. His 2010 retrospective organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art traveled to New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. He was the first contemporary artist to have his own iPhone app. There’s even been a short documentary made about him that was narrated by Tom Waits. So, what makes Baldessari one of the most important artists working today? Read on for a close look at his ironic, thought-provoking work.

THE END OF PAINTING

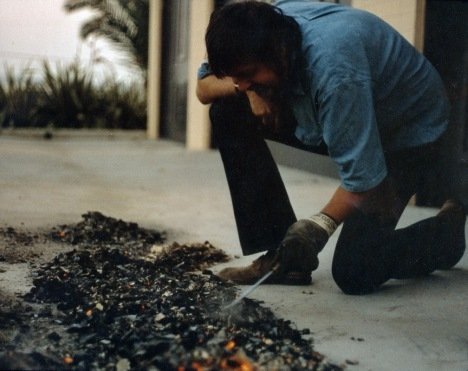

Photograph of Cremation Project (1970)

Photograph of Cremation Project (1970)

Early on, when Baldessari was still a relatively unknown professor at CalArts, he included an essay question on his list of optional assignments: “How can we prevent art boredom?” Baldessari, meanwhile, was preparing his own answer. In 1970, the artist burned most of his paintings from the previous 13 years as part of Cremation Project, sparing only a few—some text works that made sly remarks about the meaning of art, and some others that combined painting and photography. His reason for doing it: He already had slide reproductions of the paintings, and nobody was going to buy them anyway.

A year later, in what might be seen as a follow-up, Baldessari made another career-defining move. For I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art, Baldessari wrote the title phrase repeatedly on a sheet of lined paper as a sort of after-school-detention project. It was a pledge as much as it was a form of penance, requiring him to enact over and over again what it meant to make tedious art, with the intention of afterwards starting anew.

WHAT ART ISN’T

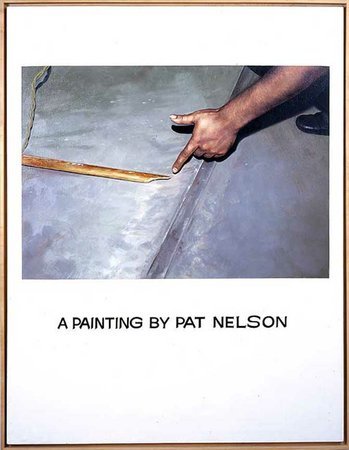

A Painting by Pat Nelson (1969)

A Painting by Pat Nelson (1969)

Because Baldessari started working during Minimalism’s heyday, it’s not surprising that he had an interest in discovering why artists took art so seriously. The ideas behind art quickly became one of Baldessari’s targets. In 1972, Baldessari made John Baldessari Sings Sol LeWitt, a film of Baldessari intoning LeWitt’s writings on art as an homage to his seminal text, and a parody of the self-seriousness that surrounded it. A few years prior, Baldessari made Commissioned Paintings, a series of works in which he hired amateur painters to create images of hands pointing at things. Baldessari then added a caption proclaiming the work as a painting, thus dissolving the distinction between amateur art and high art. Now, it was the viewer who got to determine what art was or wasn’t.

DOING IT WRONG

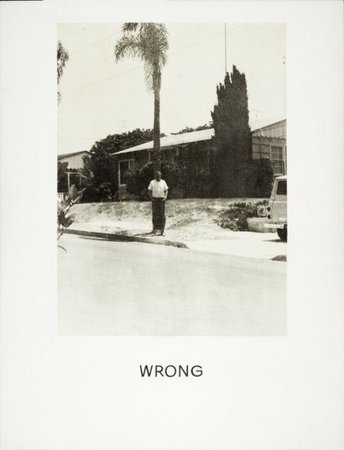

Wrong (1967)

Wrong (1967)

For Wrong, Baldessari painted of a photograph of himself standing on the side of a street in Los Angeles and a caption that says “WRONG.” What’s wrong about Wrong? Is it the composition, the overall aesthetic, the fact that the artist is standing in front of a palm tree? Baldessari never tells us. Instead, he makes us question whether a work of art can be “wrong” at all. Like many of Baldessari’s works, this seminal piece explores the ways that language can completely change the meaning of an image.

PHOTOGRAPHS, FILM STILLS, AND DOTS

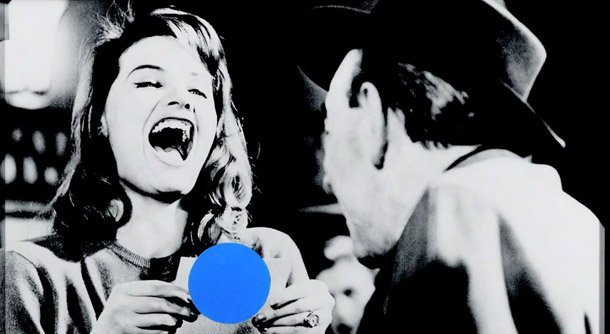

Detail of Heel (1986)

Detail of Heel (1986)

Baldessari repeatedly told his students that drawing from life was a worthless pursuit. Instead, he only had them work from reproductions, citing these copies as the true source of art. From there, it was only a natural progression that Baldessari began appropriating photographs and film stills for his own work. The concept of unoriginality had always been of interest to Baldessari, and incorporating photographs and film stills into his art became yet another way of exploring that.

But Baldessari had also always had an interest in making the unoriginal original again. When Baldessari came upon some colored stickers on produce at grocery stores, he found the simple method of demarkation and concealment strangely fascinating. Quickly, these dots appeared everywhere on appropriated film stills and other found photographs. The dots would obscure from view the areas of obvious interest—often faces—and force viewer to see the pictures in new, more formal ways. The dots’ colors also created a tension between the original and the unoriginal, contributing clichéd associations (red = danger, for example) when juxtaposed with their subject matter, and often yielding strange, surreal results. Over time, Baldessari added further methods of concealing and otherwise denaturing the found images he worked with, filling in body parts (or entire figures) with blank colors, for instance.

THE BEGINNING OF PAINTING

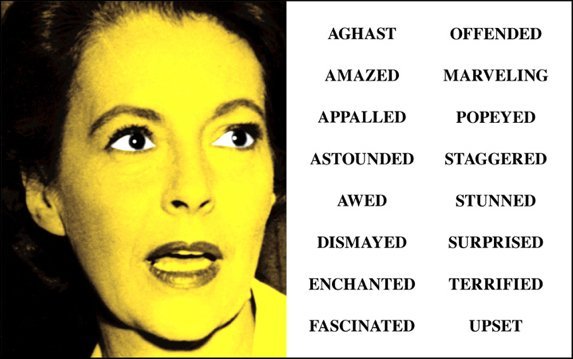

Prima Facie (Third State): From Aghast to Upset (2005)

Prima Facie (Third State): From Aghast to Upset (2005)

In the last 20 years, Baldessari has returned to painting, often creating dramatically shaped canvases that echo the work of artists like Ellsworth Kellyand Jean Arp. For his more recent "Goya" and "Prima Facie" series, the artist reinvestigates old themes in new ways—text and image are compared again, and art history gets spoofed repeatedly. What does a paperclip have to do with the word “and?” Is that shade of white actually “elephant pink” or “mayonnaise?” These are the questions Baldessari continues to ask with his work, which is still just as wryly entertaining as it was in 1967.