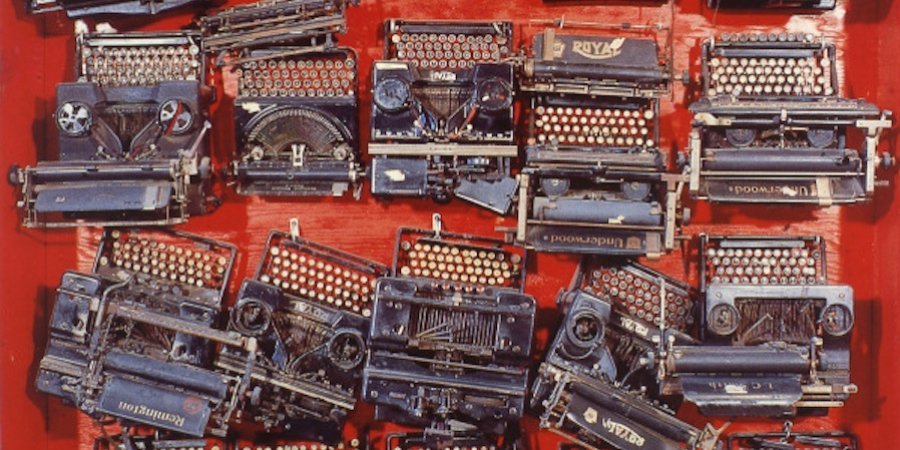

Taking a step forward from Marcel Duchamp’s readymade, which presented found objects like bottle racks and snow plows as preexisting works of art, the French-born artist Arman created his first accumulation in 1960 by putting together manufactured items of the same kind and transforming them into a new amalgamated object—a unique kind of sculpture. His accumulations consisted of objects welded together or fused to one another with polyester, plexiglass, or concrete and then presented, carefully piled-up, on wood panels or in boxes.

Alarm Clocks (Reveils) (1960)

Alarm Clocks (Reveils) (1960)

What kind of objects? Over his career, Arman employed toothbrushes, clocks, tools, utensils, washing machines drums, trophies, shopping carts, gas masks, painting tubes and brushes, fossils, and sneakers, among many everyday items. He never reproduced objects—instead, he found them in garbage bins, thrift shops, or dumps. "It runs in the family," he once said, explaining that his grandmother was an avid collector of all things who had thousands of wine corks that she kept neatly arranged in her house.

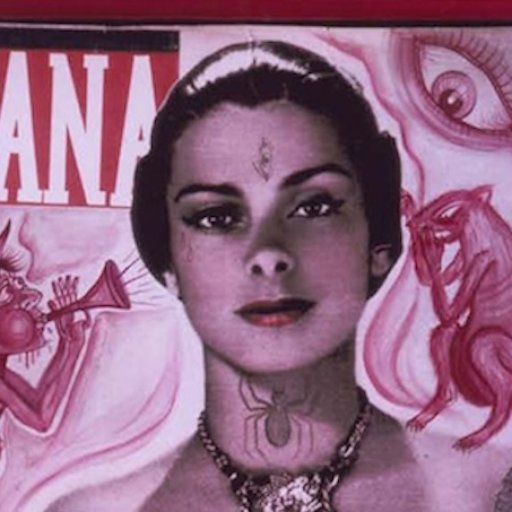

One of Arman's early "cachet" paintings

One of Arman's early "cachet" paintings

In 1955, Arman accidentally came upon a group of rubber stamps and began working with them, making random compositions. He named them "Cachets" and considered these his first personal artworks. Rubber-stamping had been utilized in art before—Kurt Schwitters's Dada collages being one example—but it was Arman who applied the technique in a systematic and repetitive way, exploring the gesture, the reproduction of image, and the notion of quantity, all ideas that prefigured Warhol's repetitive use of images. He worked directly with objects rather than starting on a blank surfaces, which opened up new possibilities of art-making. Years later, rubber-stamping became widely used in conceptual art, by Fluxus artists, for instance, and by Ray Johnson in his mail art.

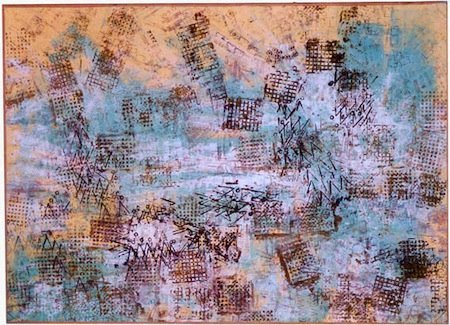

One of Arman's "poubelles"

One of Arman's "poubelles"

Although Arman (who passed away in 2005) utilized rubber stamps through all his life, he abandoned the methodical use of this medium in the late '50s. In 1960 he signed a "Nouveau Realisme" manifesto along with artists Martial Raysse, Yves Klein, and Jean Tinguely, united under the umbrella of the influential art historian Pierre Restany. The movement asserted new ways of perceiving the real and was committed to the re-examination of everyday objects' artistic possibilities—an approach that Arman typified with such projects as the assemblages he would create out of garbage (his "Poubelles"), interested as he was in showcasing the beauty of found elements regardless of what they were. Arman's tenacious use of waste and garbage, in fact, positions him as one of the first artists to address environmental issues.

In 1960, Arman filled the Galerie Iris Clert in Paris with garbage, creating his piece "Fullness." (Yves Klein's famous The Void had radically emptied out the same gallery space a year before, radically presenting the absence as art.) Because of this show, Arman became notorious not only for his provocative gestures, but also for the smell that emanated from the gallery. “The perfect knowledge of the visual impact of objects is a part of my work," he said. "I have a very simple theory. I have always pretended that objects themselves formed a self-composition. My composition consisted of allowing them to compose themselves.”

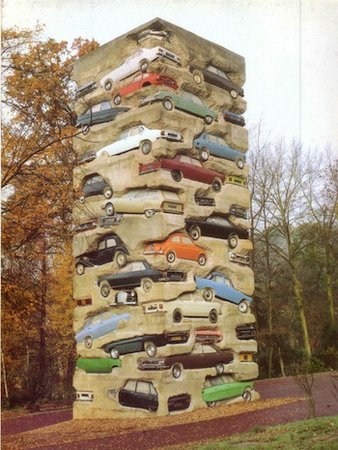

Long-Term Parking (1982)

Long-Term Parking (1982)

Stretching the “expression by the quantity” idea, Arman created his first monumental sculpture in France in 1982: Long-Term Parking, a 60-foot-high column of five-dozen automobiles kept together with 40,000 pounds of concrete. It's an impressive work that makes evident the undeniable mass of objects and our relationship to them by underlining the proportions of the cars and of the column they composed with that of a human being. In 1995 he piled up 83 tanks and military vehicles, creating a 105-foot-high monument in Beirut, a work commissioned by the Lebanese government.

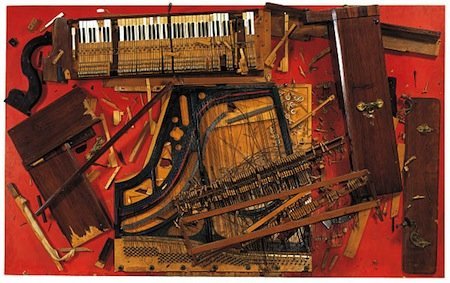

After his participation in the Museum of Modern Art's seminal 1961 exhibition "The Art of the Assemblage," Arman began spending more time in New York, a city that fascinated him because he considered it to be one giant accumulation. At this time, he began to tear, break, burn, slice, and smash of objects—musical instruments, bicycles, and cars, for instance—that he then often rearranged on canvas. He called these artworks "Colères" or "Coupes" ("Rages" or "Cuts"), and explained that his passion for cutting and exposing objects came from his childhood, when he visited world fairs with his father and saw cars, cameras, and other machines cut open in order to reveal their internal mechanisms.

One of Arman's sculptures of a smashed piano

One of Arman's sculptures of a smashed piano

“There is no difference between accumulating objects or smashing an object," he said. "[One thousand] objects are not fundamentally different from 1,000 pieces of the same object. There is also a logic to destruction. If you break a rectangular box, you arrive at something cubist. If you break a violin you get something romantic.”

Arman was a rat pack all the way. His relationship with objects was quite extraordinary—personal, intense, symbiotic—and his profound understanding of material forms is reflected in the exactitude with which he manipulated them. His obsession with objects continued into his activities as a collector, which were impossible to dissociate from his artistic endeavors. Living in New York, Arman amassed one the greatest African art collections in this country, part of which is being shown at the Paul Kasmin Gallery this November; rare Bakota reliquary figures from Gabon are among his most prized pieces. But he collected wide and far outside of African art as well, forming roughly 17 diverse collections of bakelite radios, wrist watches, Japanese armor, European pistols, juke boxes, Tiffany lamps, and other categories and surrounding himself with his treasures in the spacious Tribeca studio that he moved into in 1984.

Arman's influence is unmistakable today, found everywhere from Damien Hirst's pharmacy assemblages and sliced animals to Jeff Koons's accumulation of vacuum cleaners, Yoko Ono's "destruction" performances, or Droog's "85 Lamps Chandelier." Assemblage art and accumulations that display the collecting impulse are modes of art-making that could be seen prominently in this year's Venice Biennale, where several artists presented highly personal collections of objects they had discovered, including Vladimir Peric's installation of hundreds of rubber Mickey Mouse toys mounted on a wall at the Serbian Pavilion and the Italian artist Linda Fregni Nagler's 1,000 found sepia photographs of anonymous babies displayed in long orderly rows in Cindy Sherman's curated section.

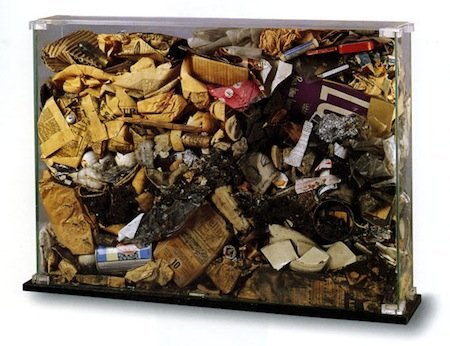

One of Arman's paintbrush assemblage "paintings"

One of Arman's paintbrush assemblage "paintings"

Other notable accumulation installations that followed Arman's example include Martha Rosler's ongoing Monumental Garage Sale, which filled diverse spaces with second-hand knickknacks since 1973; Song Dong's 2009 installation in MoMA's atrium of all the objects that his mother hoarded in her Beijing home over 50 years, meticulously organizing and pairing thousands of familiar objects by their resemblances; the Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco's scientific-style catalogs of found objects, organizing them in methodical displays; Mark Dion's taxonomical pieces of wild objects that allude to the relationship between humankind and its environment; and many of Fishli/Weiss's memorable installations, such as their accumulation of 800 magazine advertisements that they showed in vitrines at Matthew Marks in 2010.

Arman often claimed that when he saw other artists making artworks that were influenced by him, he knew had to reinvent his work. Were the artist alive today, he would never cease needing to reinvent himself.