In countless nursery rooms, children gaze at entrancing sculptures suspended above cribs, which spin in harmonious balance. What many might not realize, though, is that “mobiles” were actually named by French artist Marcel Duchamp in reference to avant-garde sculptures made by Alexander Calder beginning in 1931. A pun on the French words for “motion” and “motive,” mobiles are a form of suspended sculpture initially intended to invoke the abstract paintings of Joan Miró and Jean Arp. The ubiquity of Calder’s innovation has led to the mobile overshadowing much of the artist’s oeuvre. However, Calder’s career was in fact diverse, encompassing drawings, paintings, and prints in addition to his well-loved sculptures.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1898, Calder was a third-generation sculptor on his father’s side (a sculpture of a young, nude Calder by his father is owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art), and a second-generation painter on his mother’s. However, he initially studied mechanical engineering, before enrolling at the Art Students League from 1923–25. Calder is claimed by both the Americans and the French after he moved to Paris for several years, beginning in 1926.

This Friday, June 9th, Whitney Museum of American Art opens a comprehensive exhibition of Alexander Calder’s work, Calder: Hypermobility , including “an expansive series of performances and events,” aimed at revealing the work’s “relationship to performance and the theatrical stage.” In addition, this past February, the Guggenheim Museum re-installed Calder’s iconic sculpture Red Lily Pads to its central location in the rotunda to much fanfare after it was removed for significant restoration several years ago. With these recent developments in mind, here’s a survey of Calder’s artistic achievements, both within kinetic sculpture and elsewhere.

Wire Sculptures

Alexander Calder,

Romulus and Remus

, 1928; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Alexander Calder,

Romulus and Remus

, 1928; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Shortly after arriving in Paris, Calder merged his mathematical and artistic background by constructing mechanical toys, which he submitted to salons. Simultaneously, Calder began making figurative sculptures from shaped wire. These early works were, for Calder, a form of “drawing in space,” and became the subject of the young artist’s first solo show in Europe in 1929.

RELATED: 10 Remarkable Recent Sculptures That Show Where the Medium Is Going Today

Cirque Calder

Around the same time as Calder began making his wire sculptures, he befriended a group of artists who were coalescing around the Montparnasse neighborhood of Paris, including Piet Mondrian , Joan Miró, and Marcel Duchamp. Calder began a project inspired by his childhood love of circuses, which became one of the artist’s most beloved works. Cirque Calder , first exhibited in 1929, was, along with Jeff Koons ’s retrospective, the final exhibition of the Whitney’s uptown location before it relocated to its current space. While the museum exhibited the works as static sculptures, they noted that “In Paris, Calder’s audience would sit on a low bed or crates, munching peanuts and using the noisemakers while Calder choreographed, directed, and performed Calder’s Circus , narrating the actions in English or French. Accompanied by music and lighting, performances could last as long as two hours.”

Mobiles

Calder,

Red Lily Pads

, 1956; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Calder,

Red Lily Pads

, 1956; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Calder’s early wire sculptures, although static, retained an element of light fluidity. However, following the performative circus works, Calder’s sculptures began to become more overtly kinetic. Inspired by the abstract works of Mondrian, Jean Arp, and others, Calder refocused his sculptures on the moveable elements, in increasingly abstract executions. Sculptures of abstract shapes connected by hooks and wires could be controlled by various levers and mechanisms, in challenge to notions of sculpture as an essentially static medium. In 1931, Duchamp dubbed Calder’s kinetic sculptures “mobiles,” in reference to his own kinetic works.

Other early advocates of Calder’s mobiles were curator Alfred Barr, who included Calder in MoMA’s 1936 exbhibition “Cubism and Abstract Art,” and Jean-Paul Sartre, the father of existentialism, who wrote in a 1946 exhibition catalog, “The forces at work are too numerous and complicated for any human mind, even that of their creator, to be able to foresee all their combinations. For each of them Calder establishes a general fated course of movement, then abandons them to it: time, sun, heat and wind will determine each particular dance.”

Calder continued to manufacture mobiles throughout his entire career. One of the most famous of these works is Red Lily Pads (1956), pictured above, which has been an iconic fixture of the Guggenheim Museum in New York since it was installed above the lobby’s pool for Calder’s retrospective in 1964. (The sculpture was removed several years ago for restoration following damage caused by coins thrown into the pool, and was recently rehung for the Guggenheim’s current “Visionaries” exhibition.)

Stabiles and Monumental Works

Calder,

Man

, 1967

Calder,

Man

, 1967

Despite the popularity of his mobiles, Calder continued to create static sculptures, which Arp named “stabiles” in differentiation. Like the mobiles, stabiles are geometric abstractions that seem to support their weight seemingly impossibly. Meanwhile, in the 1950s, Calder’s works began to grown in scale as the artist accepted prominent commissions—for example, the 1968 Summer Olympics, John F. Kennedy airport in New York City, and UNESCO headquarters in Paris.

RELATED: Art Road Trip! 10 Public Sculptures Worth Driving Cross-Country For

The static stabiles proved more resilient in larger scale than the mobiles, which were designed to move with wind and other natural elements. Some monumental stabiles, such as La Grande Vitesse in Grand Rapids, Michigan, were controversial upon their commission due to their immense scale and frequent use of Calder’s signature jarring red hue. However, La Grande Vitesse , the first public work funded by the NEA, is now a beloved icon of Grand Rapids.

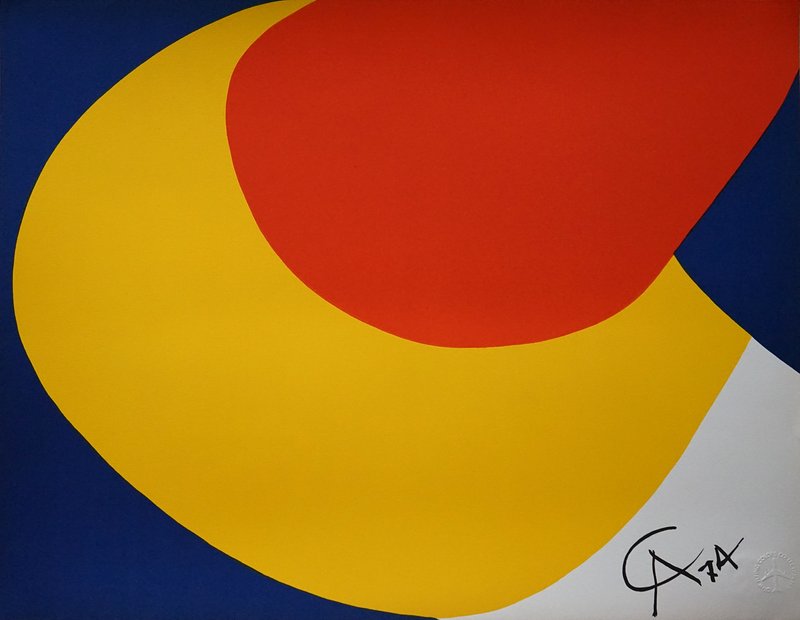

Painting and Printmaking

Calder’s

Convection

(1974) is available on Artspace for $1,100

Calder’s

Convection

(1974) is available on Artspace for $1,100

Undoubtedly, Calder is best-known today for his sculptures—which are included in collections at the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim Museum, the Whitney, the Centre George Pompidou, and elsewhere—Calder was a prolific painter and printmaker, like his friend Fernand Léger, since the beginning of his career. Calder’s works even occupy their own room at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

While Calder’s early paintings were realistic, with esoteric, stylized figuration, his later paintings and prints were composed of geometric abstractions, often rendered in deep saturation with gouache, swirl with vibrancy reminiscent of his sculptural works. A 2009 exhibition at the Bruce Museum in Connecticut, “Alexander Calder: Printmaker” collected a number of printed works “in an effort to uncover one of the artist’s lesser-known artistic practices.” The museum also notes that despite the stature of his sculptures, Calder was exceptionally prolific producing prints, particularly during the 1940s and 50s.

Jewelry and Stage Design

Calder,

Harps and Heart

, 1937

Calder,

Harps and Heart

, 1937

When he was a boy, Calder constructed jewelry for his sister’s dolls. Throughout his career, Calder continued to fabricate jewelry, often giving away pieces to friends, such as Georgia O’Keeffe , and the wives of Duchamp, Luis Buñuel (the famed surrealist filmmaker), and Marc Chagall . According to critic Roberta Smith, Peggy Guggenheim wore an earring designed by Calder during the opening of her influential gallery in New York.

RELATED: Three Figurative Sculptors Bringing the Form into the 21st Century

In addition to designing jewelry, Calder was frequently commissioned to design sets for theatrical performances, in part due to their resonance with dance and harmonic rhythm. Most notably, Calder’s Decor for Satie’s “Socrate” , consisting of a steel mobile, was designed for composer Erik Satie’s 1936 masterpiece. Decor for Satie’s “Socrate” is also an example of an early monumental work, before Calder focused these large-scale pieces on his stabiles.