After MoMA's Bruce Conner retrospective this past summer and the Whitney's celebrated "Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art" survey, experimental film finally seems to be back on the New York art world's agenda. But for a long time, film was the thorn of art history after that thing called "Hollywood" came along, which threatened the avant-garde film's separation from mainstream cinema.

Experimental or avant-garde film can be traced all the way back to canonical artists like Marcel Duchamp and Many Ray , but what happens post-Hollywood? Here's a quick guide to postwar experimental film in the United States, ranging from Expanded Cinema of the '60s to the origins of underground queer cinema with artists like Jack Smith. We've got the critics and the crucial texts you need to read (each essay has been linked) and the artists you need to know.

Expanded Cinema of the '60s

Critic to Know:

GENE YOUNGBLOOD

Seminal Text to Know:

Expanded Cinema

(1970)

Gene Youngblood was a crucial theorist of media arts and alternative cinema during the 1960s and '70s. He was the first to consider video an art form, folding computer and media art into the genre. His seminal book

Expanded Cinema

was the first to define one of the most heterogeneous movements in film history. As you can probably guess from term, “expanded cinema” refers to cinema that expands beyond the bounds of traditional uses of celluloid film, to inhabit a wide range of other materials and forms including video, television, light shows, computer art, multimedia installation and performance, kinetic sculpture, theater, and even holography. Mixing psychedelic consciousness and Marxist theory, Youngblood explains “when we say expanded cinema we actually mean an expanded consciousness.” So if you’re still confused after seeing Stan Vanderbeek’s immersive psychedelic

Movie Drome

(1965) at the Whitney’s Dreamlands exhibition this year, take a look at the first chapter of Youngblood’s

Expanded Cinema

(the entire book is available on the PDF link above).

ARTISTS TO KNOW:

Stan Vanderbeek,

Carolee Schneemann

, Malcom Le Grice,

Mark Leckey

Interior view of Stan Vanderbeek's

Movie Drome

(1965). Photo: Peter Moore

Interior view of Stan Vanderbeek's

Movie Drome

(1965). Photo: Peter Moore

Found Footage Film

Critic to Know:

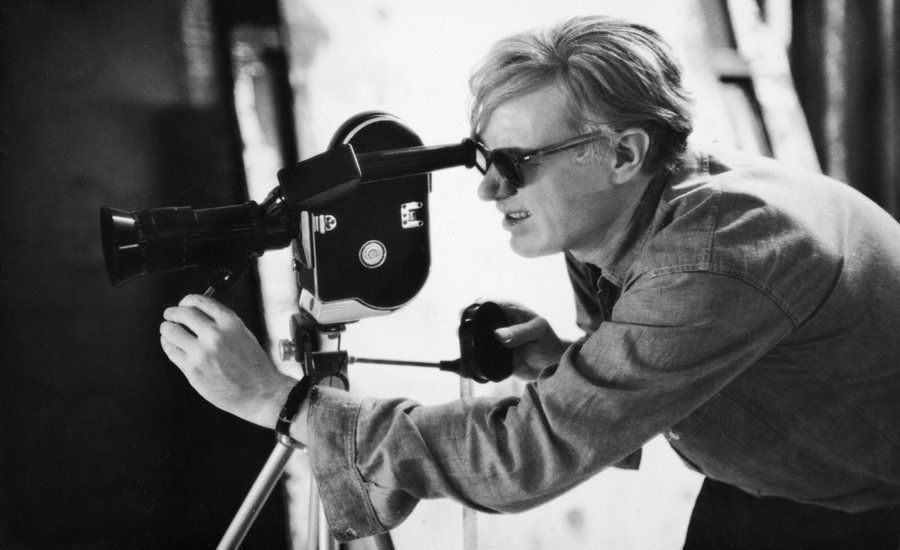

CRAIG BALDWIN

Seminal Text to Know:

From Junk to Funk to Punk to Link : A survey of found-footage film in San Francisco Bay Area

Any narrative of postwar experimental film has to begin in California. Reacting against the expansion of Hollywood, experimental film was, in essence, a form of cinema that radically opposed the aesthetics and politics of mainstream media. The rise of psychedelic light shows, beatnik films, and alternative outdoor venues like Canyon Cinema (a filmmakers cooperative started by Bruce Baillie that exhibited independent, non-commercial film) all lead the Bay area to become an epicenter of avant-garde film in the second half of the century. Experimental filmmaker Craig Baldwin’s essay “From Junk to Funk to Punk to Link” is a must-read for anyone interested in a short genealogy of found footage film, seen in likes of Bruce Conner and Gunvor Nelson's work. A pioneer of found-footage himself, Baldwin remains in San Francisco to this day where he continues to program content for Artist’s Television Access, which broadcasts art films on Public-access television. For more on experimental film in the Bay Area click here to see the Berkeley Art Museum’s catalogue, “Radical Light: Alternative Film and Video in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945-2000.”

ARTISTS TO KNOW:

Bruce Conner

, Craig Baldwin, Robert & Gunvor Nelson, Chick Strand

Still from Bruce Conner's

Three Screen Ray

(2006).

Still from Bruce Conner's

Three Screen Ray

(2006).

Structuralist Film

Critic to Know:

PETER GIDAL

Seminal Text:

"Introduction" of

Structural Film Anthology

(1976)

Structuralist or Materialist film is what

Minimalism

was to sculpture in the 1960s. In his paradigm book

Structural Film Anthology

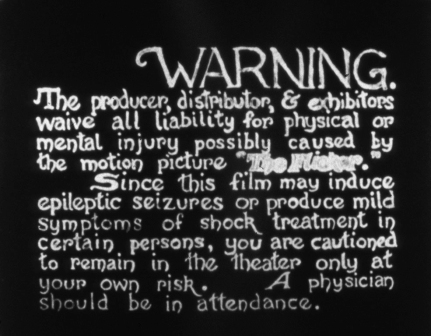

(1976), English theoretician and filmmaker Peter Gidal writes frankly that "Structural/Materialist film attempts to be non-illusionist" in its attempt to "demystify the film process." Structuralist film, like Minimalist objects, doesn't actually represent anything. Instead, it exposes the relations between the camera and the way an image is presented, and explores the characteristics specific to the medium—spotlighting elements like flatness, grain, light, and movement. Tony Conrad's film

The Flicker

(1966), exemplary of the movement, consists purely of rapidly alternating black and white frames, achieving a kind of strobe light effect. If you're hesitant to submit yourself to the full fifteen minutes of

Flicker

(we don't blame you), then take a look at Gidal's introduction in the

Structural Film Anthology

to get a better idea about what this strange movement was really about.

ARTISTS TO KNOW:

Tony Conrad, Hollis Frampton, Michael Snow

Still of the initial "Warning" in Tony Conrad's

The Flicker

(1966)

Still of the initial "Warning" in Tony Conrad's

The Flicker

(1966)

Feminist Film

Critic to Know:

LAURA MULVEY

Seminal Text:

Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema

(1975)

Laura Mulvey is a British feminist film theorist, currently teaching film and media studies at Birbeck, University of London. Drawing from psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan, Mulvey’s seminal essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975) was crucial in inaugurating the intersection of film theory, psychoanalysis, and feminism. Mulvey was the first to term what has come to be known as the “male gaze.” In the essay, she argues that classic Hollywood cinema inevitably positioned the spectator as a masculine and active voyeur, and the passive woman on screen as object of his scopic desire. The essay challenged conventional film theory and paved the way for an entire era of feminist artist’s work on the male gaze (think

Cindy Sherman’s

Untitled

film stills.). After reading “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” you’ll never look at a Hitchcock or John Wayne the same.

ARTISTS TO KNOW:

Peggy Ahwesh, Barbara Hammer,

Laurie Simmons

Cindy Sherman,

Untitled Film Still #21

, 1978

Cindy Sherman,

Untitled Film Still #21

, 1978

Camp & Queer Cinema

Critic to Know:

SUSAN SONTAG

Seminal Text:

"Notes On Camp" (1964)

Susan Sontag was one of the most revered writers, filmmakers, political activists, and critics of her generation. Sontag wrote extensively about photography, culture and media, AIDS, and the Vietnam War. Sontag’s most well known essay, “Notes on Camp,” is crucial for anyone interested in the legacy of queer filmmakers like Jack Smith, who is most known for his banned film Flaming Creatures (1963) that right-wing politician Strom Thurmand mentioned in anti-pornography speeches. Although Sontag does not define camp, she writes that the essence of a “camp” sensibility lies in “its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” For anyone interested in the kitschy, exotic films of Jack Smith and underground Queer Cinema, Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” is a must.

ARTISTS TO KNOW:

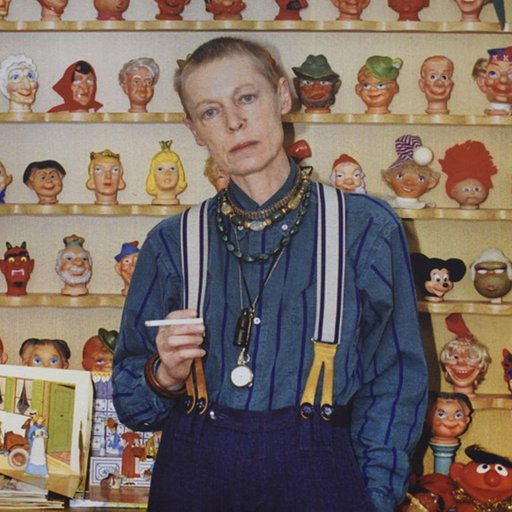

Jack Smith,

Andy Warhol

,

Isaac Julien

Still from Jack Smith's

Flaming Creatures

(1963)

Still from Jack Smith's

Flaming Creatures

(1963)