Recognizable to even the most casual of art enthusiasts,Andy Warhol’sCampbell’s Soup Cans and Marilyn prints represent the rare artworks that have passed fully into the realm of popular culture through innumerable imitations, sendups, and homages—an appropriate turn of events, given their status as the twin lodestones of Pop Art as we know it. But why did the Paladin of Pop settle on these iconic images as the vehicles of his new aesthetic approach, and how did they achieve their legendary renown within a skeptical art world? Read the real story for yourself in this excerpt fromPhaidon’sAndy Warhol, written by the curator and art historian Joseph D. Ketner II.

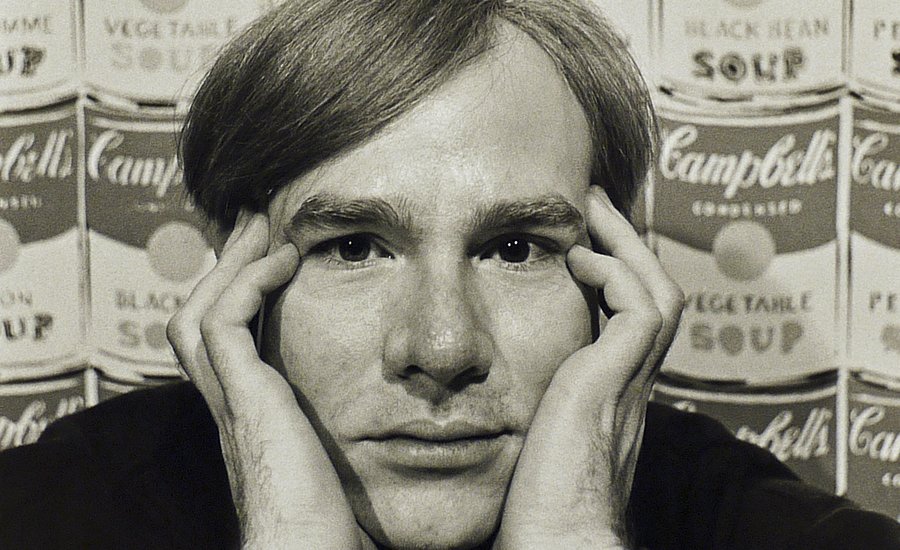

Reflecting on his career, Warhol claimed that the Campbell’s Soup Can was his favorite work and that, “I should have just done the Campbell’s Soups and kept on doing them… because everybody only does one painting anyway.” Certainly, it is the signature image of the artist’s career and a key transitional work from his hand-painted to photo-transferred paintings. Created during the year that Pop Art emerged as the major new artistic movement, two of his soup can paintings were included in the landmark Sidney Janis Gallery exhibition, “The New Realists.”

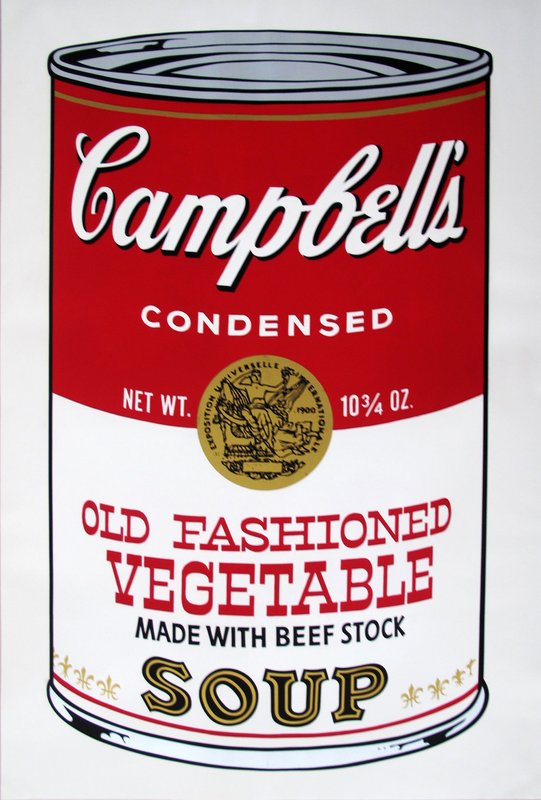

In the spring of 1962, Warhol had been working on his new renditions of ads and comic strips when he saw Roy Lichtenstein’s comic-strip paintings at Leo Castelli Gallery. Soliciting suggestions for subjects to paint, he asked a friend, who suggested he choose something that everybody recognized like Campbell’s Soup. In a flash of inspiration he bought cans from the store and began to trace projections onto canvas, tightly painting within the outlines to resemble the appearance of the original offset lithograph labels. Instead of the dripping paint in his previous ads and comics, here Warhol sought the precision of mechanical reproduction.

Campbell's Soup II: Old Fashioned Vegetable (FS II.54), 1969—available on Artspace

Campbell's Soup II: Old Fashioned Vegetable (FS II.54), 1969—available on Artspace

At this time he received a return studio visit from Irving Blum of Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles, who was expecting to see comic-strip paintings and was surprised by the new soup cans, immediately offering the artist a show that summer. Expanding his subject, he decided to paint one of each of the thirty-two varieties of Campbell’s soups. Blum exhibited the cans on shelves running the length of his gallery.

The exhibition caused a mild sensation in Los Angeles. The more daring members of the youthful art and film community were intrigued by their novelty. Most people, however, treated them with indifference or outright disdain. A nearby art dealer parodied the show by displaying a stack of soup cans, advertising that you could get them cheaper in his gallery. Blum had sold five of the paintings before he recognized that the group functioned best as a single work of art. He bought back the works already purchased, including one from Dennis Hopper, then offered to buy the set from Warhol in installments for the modest sum of $3,000.

Campbell's Soup Cans, 1962

Campbell's Soup Cans, 1962

With his Campbell’s Soup Cans installation at Ferus Gallery, the artist realized the possibility of creating works in series, and the visual effect of serial imagery. He continued making variations on his Soup Cans, stenciling multiple cans within a single canvas and so amplifying the effect of products stacked in a grocery store, an idea that he would later develop in the box sculptures. He also realized that the serial repetition of an image drained it of its meaning, an interesting phenomenon most poignantly presented in his Disasters, in which the constant exposure to their graphic displays of violence numbs the senses. And, perhaps the most significant outcome of this series was the artist’s push towards printing to achieve the mechanical appearance that he sought in his paintings.

While Campbell’s Soup Can may be Warhol’s signature image, his Marilyn paintings epitomize his obsession with celebrity, beauty, and death. Beginning with the soup cans, the artist edged increasingly closer to commercial printing. Seeking to replicate the appearance of commercial products in his paintings, Warhol pushed his exploration of reproductive techniques to include rubber stamps, stencils, and silkscreens.

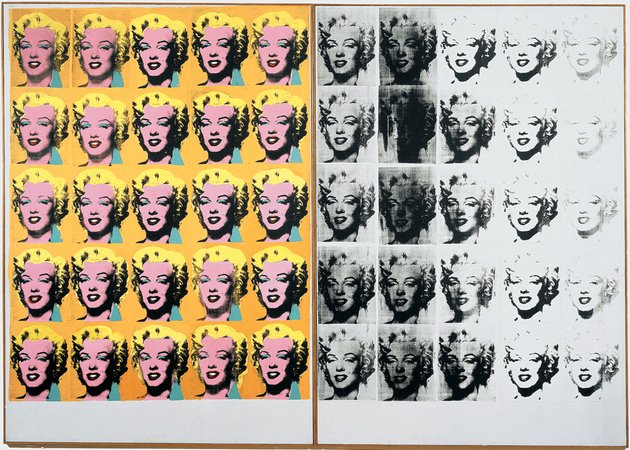

During the summer of 1962, he learned from his printer about the photo-transfer silkscreen. Returning to his childhood fascination with celebrity photos and his commercial art technique of using photo cuttings, he began his experiments in photo-transfer silkscreening with images of movie stars. At that moment, on August 5, 1962, Marilyn Monroe committed suicide. Recognizing the confluence of celebrity and tragedy in this unique event, Warhol embarked on his largest series so far, creating literally thousands of paintings and prints of Marilyn, that would establish his critical and popular success as an artist.

Marilyn Diptych, 1962

Marilyn Diptych, 1962

Warhol had now found the medium that best suited his ambition to mirror mass-culture icons and products, and he moved into two signature bodies of work: the disasters and the celebrities. Both of these subjects were realized in the portraits of Marilyn. Warhol had assembled a huge collection of publicity photos of the silver screen sex symbol, selecting one as the source material for his silkscreens. In this series the artist developed the silkscreen process that he would perfect over the ensuing decades. Contrary to expectations, Warhol would paint the canvas in a variety of colors and then screen the image of Marilyn on top. The misregistration of the painting and the screenprint created a dynamic surface that he enhanced with a broad, spectrum of colors.

The act of printing and painting in multiple variations shows Warhol playing with typical commercial art processes in order to explore the range of graphic possibilities in an image. In his canvases of Marilyn, Warhol demonstrated his extraordinary sense of color, introducing metallic paints and day-glow colors, and beginning to explore the brilliant colors that would electrify his subsequent Pop paintings. But more significantly, with Marilyn he co-opted the photographic means of mass communication and captured the public gaze with an icon of contemporary culture that appealed to our most base emotions: fame, lust, and sense of mortality. By isolating her sensuous lips into a frieze, he crystallized her sex-symbol appeal.

Gold Marilyn Monroe, 1962

Gold Marilyn Monroe, 1962

Marilyn was the centerpiece of Warhol’s solo exhibition at the Stable Gallery in November 1962. Gold Marilyn Monroe, a memorial to the recently deceased celebrity, greeted visitors at the entrance to the show. On the heels of “The New Realists” exhibition that had opened one week earlier, this show was an instant hit and Marilyn was the leading star. The architect Philip Johnson bought the painting and donated it to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, launching Warhol on a successful career as an artist. It has also been argued that Warhol crafted Marilyn into an idol. At this point in her film career, she was a fading star. The popularity and proliferation of Warhol’s image of Marilyn revived her reputation as well as assuring the ascendancy of Warhol as a Pop star.