Despite its status as one of the most widely cited and recognizable art movements to come out of the early 20th century, Surrealism remains (perhaps appropriately) something of an enigma to contemporary art viewers. In some ways, it’s simply too strange—the paintings, sculptures, and writing that the loosely defined philosophy has produced appear to have little in common beyond an insistence on the part of their creators that they refer to the world of dreams and intuition. In this excerpt from Phaidon’sArt in Time, we look at some of the key works to emerge from this intense and variegated artistic ferment and how they relate to one another.

[CLICK HERE TO BROWSE ARTSPACE'S SELECTION OF SURREALIST-INSPIRED WORKS]

When poet André Breton defined Surrealism in the 1924 Manifesto of Surrealism, he described an attitude that scorned the logic of accepted hierarchies, conventions, and institutions—one that sought revolution beginning with the individual and extending to the political. According to the Surrealists, in focusing on the visible, tangible world, human civilization had ignored a world of other, superior (“sur”) realities that could be found through dreams and chance aspects of life, which they termed “the marvelous.”

Salvador Dalí's The Persistence of Memory, 1931

Salvador Dalí's The Persistence of Memory, 1931

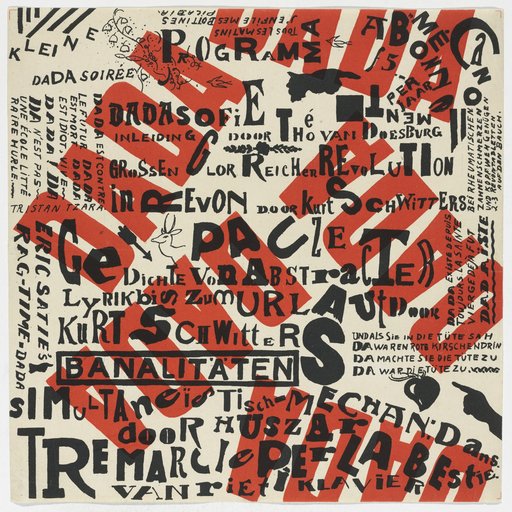

Descended from Dada, Surrealism began in Paris and spread more widely and variously than any other movement of twentieth-century art: from Britain to the Czech Republic, from found objects to oil paintings to film. Dreams, as expressed by Freud, had the potential to overcome the oppressive “reign of logic” by allowing the impossible to seem feasible and the fantastic to appear real. Likewise, the states of infancy and madness were inspirational because they represented freedom from the constraints of etiquette and the prioritization of instinct over logic. Experimental techniques, including collaborative games, were key to the movement’s achievements.

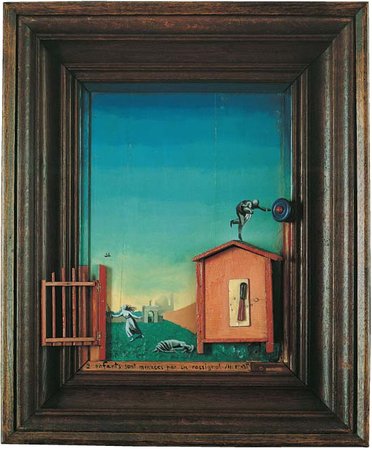

Max Ernst's Two Children are Threatened by a Nightingale, 1924

Max Ernst's Two Children are Threatened by a Nightingale, 1924

The first Surrealist experiments were linguistic and literary: it was in 1919 that Breton and Philippe Soupault first published their attempts at “automatic writing,” purportedly the dictation of pure, unmediated thought. Artists tried to find a visual equivalent to this spontaneity, but painting initially proved a challenge. The necessary preparation and techniques of painting on canvas seemed to threaten the immediacy that had been achieved in writing.

Meret Oppenheim's Object, 1936

Meret Oppenheim's Object, 1936

Artists responded in various ways, some concentrating on process, others on content. Max Ernst (1891– 1976) perfected the technique of collage and assemblage, fabricating scenes that appear strangely dramatic and yet ambiguous. In Object, by Meret Oppenheim (1913–85), an unexpected material is used to cover a familiar object and render it dysfunctional, creating an uncanny and somewhat sensual, tactile effect made all the more provocative by its creation by a female artist.

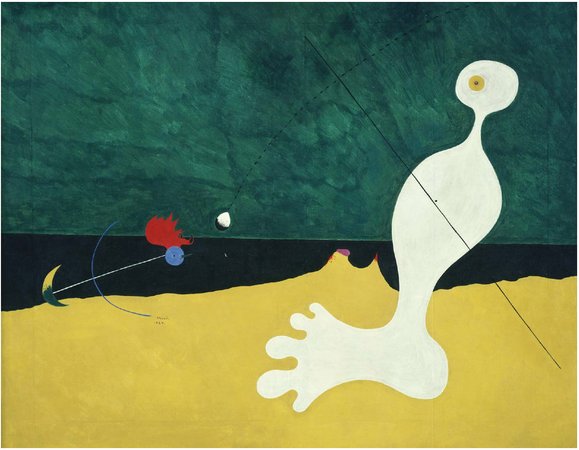

Joan Miró's Person Throwing a Stone at a Bird, 1926

Joan Miró's Person Throwing a Stone at a Bird, 1926

Nevertheless, it is for oil paintings that the movement is best known. While Joan Miró (1893–1983) developed a reductive and child-like language of indefinable signs to paint hallucinatory forms on a dream-like backdrop, paintings by Salvador Dalí (1904–89) and René Magritte (1898–1967) look like naturalistic depictions of dreams after the event, with peculiar juxtapositions that nevertheless seem entirely realistic on the level of perspective and form. However, they also contain important political and philosophical references.

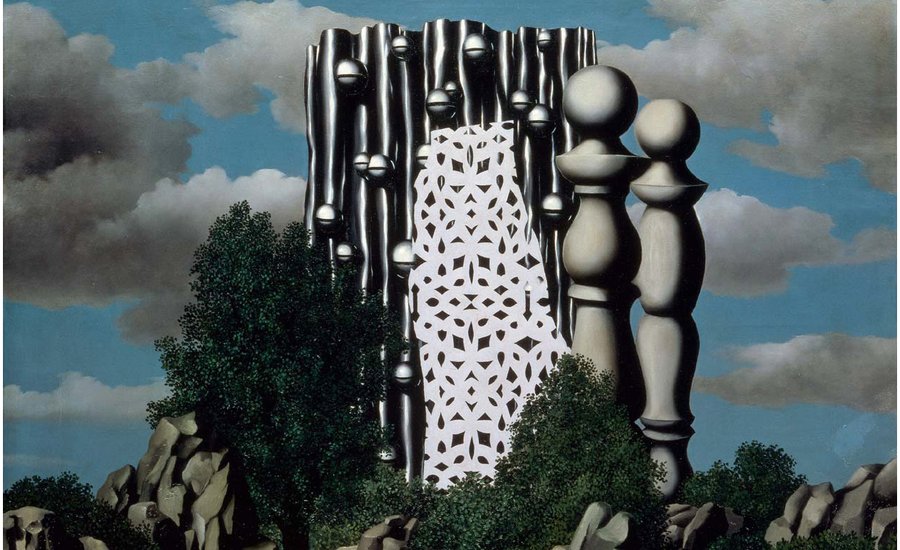

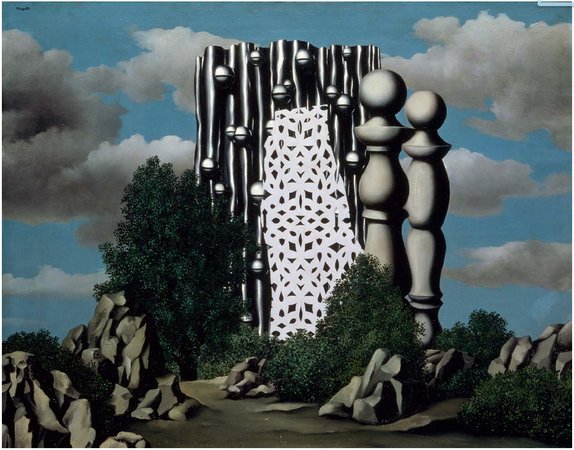

René Magritte's The Annunciation, 1930

René Magritte's The Annunciation, 1930

In Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory, measurable time melts away, and in its place are memories and perceptions that begin in dreams but persist into the waking world. The Annunciation parodies the Catholic connotations of its title, replacing the Virgin and archangel with an evocative combination of objects, announcing the birth of something new and seemingly important, but in no way connected to religion.

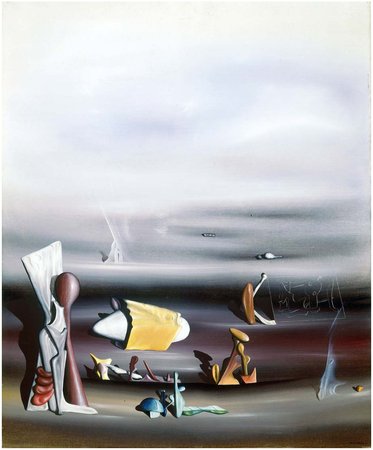

Yves Tanguy's To Construct and Destry, 1940

Yves Tanguy's To Construct and Destry, 1940

The amoeba-like abstract forms painted so precisely and perhaps even scientifically by Yves Tanguy (1900–55), might seem initially to be life forms in the process of becoming something, but the title of the work suggests simultaneous construction and destruction. The resolution of opposites and the prizing of liminal states and ambiguities were key concerns of the Surrealists and helped in challenging an objective or definitive view of reality.