If we've learned anything in the last month, it's that our once resolute institutions—from Congress and the electoral process to our favorite museums—are under fire from the marginalized groups who feel left out. These concerns and protests are nothing new, of course; art world outsiders and enfant terribles like the Guerrilla Girls and their irreverent posters, the anti-art of Dada , or Warhol’s “Oxidation” paintings have long waged war with performance, protest, and art to challenge and change the otherwise impenetrable establishment. Now, newer efforts like Occupy Museums In this short excerpt from Phaidon's Art in Time , we look back at the historical roots of the best-known movement, Institutional Critique.

By 1969 opposition in the United States to the American-led war in Vietnam was escalating, and artists were becoming increasingly involved in antiwar protests. One afternoon, four members of the recently formed art collective the Guerrilla Art Action Group staged an action in the entrance lobby of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Their ambition was to undermine the widely held belief that the institutions of art were aloof from politics, and they realized this by performing in the museum itself. Blood, concealed in bags beneath their clothes, made the performance more dramatic. There is nothing new about artists adopting overt political agendas, but this protest was distinctive for its ambition to make art politically useful by criticizing the institutions of art—and this is the meaning of Institutional Critique. A leaflet accompanying their protest called for the resignation of the Rockefeller family from the museum’s Board of Trustees because of their alleged business involvement in the manufacture of weapons destined for Vietnam.

Guerilla Art Action Group, a stylized enactment of military-induced violence, 1969

Guerilla Art Action Group, a stylized enactment of military-induced violence, 1969

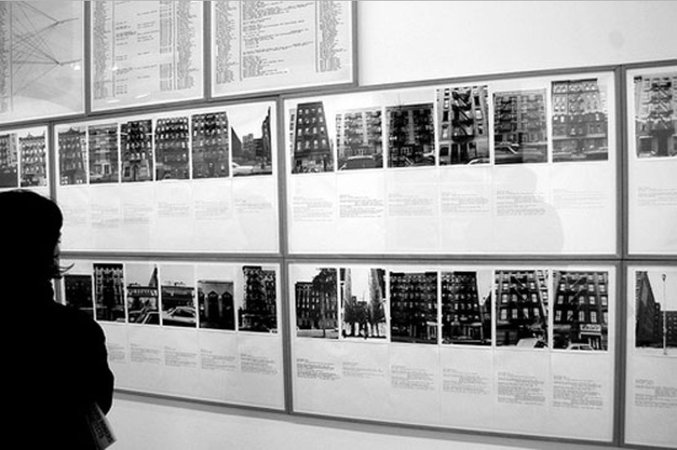

Institutional Critique draws attention to the social and cultural conditions that frame the presentation of art. These circumstances became increasingly apparent in 1971, when the New York Guggenheim Museum controversially censored two artists on separate occasions. The first concerned Hans Haacke (b. 1936), whose retrospective was about to open when the director insisted that two artworks be removed, on the grounds that they were overtly journalistic and political. These works used publicly available data to chart the business dealings of local slum landlords. When Haacke refused to comply, the exhibition was cancelled. The ensuing controversy highlighted the issue of who is entitled to determine what counts as art or politics.

Hans Haacke, Censored Works, 1971

Hans Haacke, Censored Works, 1971

Later that year, Daniel Buren (b. 1938) was obliged to withdraw from the Sixth Guggenheim International Exhibition when other contributing artists complained that his large striped banner interfered with the display of their work. Buren’s intention was to undermine the assumption that museums offered neutral viewing conditions: his goal was to expose museums as ideological constructs.

Daniel Buren, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Daniel Buren, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Over the years, Institutional Critique has interrogated the many ways in which “site” can determine art’s meaning. Michael Asher (1943–2012) explored this in 1979 by moving a bronze replica of Jean-Antoine Houdon’s George Washington from its prominent position outside the Art Institute of Chicago to an eighteenth-century display room inside the museum. The simple relocation transformed the statue of America’s Founding Father into merely a period sculpture.

Michael Asher, Jean Antoine Houden's George Washinton, 1979

Michael Asher, Jean Antoine Houden's George Washinton, 1979

Artists have exposed how the site where artwork is displayed is more than a matter of position, and that it is underpinned by profound ideological assumptions. In 1973, the American feminist artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles (b. 1939) made a performance piece that involved cleaning the public spaces of the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford, Connecticut, a gesture that highlighted the hidden labour that maintains the institutional display of art. In 1992, the African-American artist Fred Wilson (b. 1954) curated an exhibition at the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore that revealed the racial and class prejudices reflected by the museum’s holdings. In one display, ambiguously labelled Metalwork 1793–1880 , he presented slave manacles alongside luxury silverware, thus radically questioning the histories that museums choose to narrate.

Fred Wilson,

Metalwork

1793-1880, 1992

Fred Wilson,

Metalwork

1793-1880, 1992