There is perhaps no subject in the history of art that has received as much attention as the human body, whether in Paleolithic fertility statues or in 21st-century remixes of the classical reclining nude. For our first selection of works from Phaidon's groundbreaking new book Body of Art, we look to that time-honored but slippery subset of figurative art: the works meant to represent ideals of beauty. As these nine masterpieces suggest, our notions of what makes a person beautiful vary widely across time and space.

Click here to learn more about Phaidon's Body of Artand buy the book.

SLEEPING LADY OF MALTA

Artist Unknown

c. 3300-3000 BC

This iconic figurine, a modern symbol of Malta’s unique prehistoric civilization, has the massive thighs and pleated skirt characteristic of much larger stone sculptures found in the Tarxien temples of the island, but unlike their asexual forms she also possesses bounteous breasts and is clearly female. Although exaggerated, her proportions are realistic, and the complex position of the upper body is extremely sophisticated. Traces of ochre pigment survive on the polished clay, particularly on the legs. The figurine was found with other votives in a pit within the Hypogeum of Hal-Saflieni, a subterranean necropolis and cult center with rooms and corridors carved out of solid rock. The similarity of this small sculpture to monumental Tarxien statues found in temples has led to the assumption that she represents a goddess, perhaps a mother goddess. Another interpretation, drawing on her position upon a bed of some sort, suggests that she represents a mortal undergoing the rite of incubation, sleeping in a religious sanctuary in the hope of being healed or receiving divine instruction while dreaming.

IFE SHRINE HEAD

Artist Unknown

c. 12th-14th Century

According to Yoruba creation myths, the creator of the world sent an artist-god to Earth to mold humans from clay. Following that tradition, this tranquil beauty from the ancient city-state of Ife in Nigeria exhibits the two concepts of a human being in Yoruba culture: the ori inu, "inner head", the non-material essence of an individual, and the ori ade, "outer head", the physical manifestation of a person. This combination of physical verisimilitude and psychological presence is extraordinary and gives the figure life. The woman’s creased neck may represent fat, a sign of prosperity and health, and the symmetrical striations on her face reflect traditional scarification – all adding to the figure’s beauty in the eyes of the Yoruba. When the first Ife sculpted heads were discovered by the German anthropologist Leo Frobenius in 1910, they seemed so impossibly assured—for African works were then typically denigrated as crude and primitive—that Frobenius believed Atlantis must have sunk off the coast of Africa and its Greek survivors washed up on the shores of Nigeria. The discovery of more sculptures in Ife in 1938, however, showed that these were part of a purely African tradition. As a result, European concepts of African art changed forever.

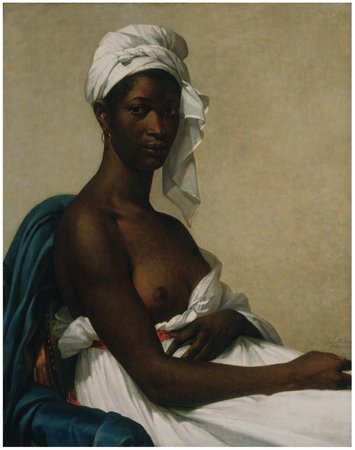

PORTRAIT OF A NEGRESS

Marie-Guillemine Benoist

c. 1800

Marie-Guillemine Benoist (1768–1826) painted this striking portrait shortly after France abolished slavery in 1794 and just before it was reinstated in 1802. At a time when racist attitudes prevailed and women had no political voice, the French artist’s choice of subject and its sympathetic treatment are subversive. Where previously the depiction of people of color in art was mostly limited to serving as an exotic "other", here the artist elevates the sitter, probably a former slave, to a subject of beauty in her own right. Painted in a Neo-Classical style, the subject gazes with quiet dignity at the viewer. This affirmative portrayal of race by a woman painter, marginalized herself due to her gender, becomes an assertion of female identity in patriarchal France. Indeed, the fledgling feminist literature of the time drew parallels between slavery and female subjugation. There is, nevertheless, inherent inequality in the sitter's semi-nude pose, which would not have been acceptable for a white woman of Benoist’s standing. Thus the black sitter’s body functions as an arena for empowerment and passive protest through the identification of Benoist, a white female artist from the moneyed class, with a nameless black servant.

STUDY OF BUTTOCKS

Félix Vallotton

c. 1884

While artists such as Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet paved the way for unidealized, realistic bodies, and Edgar Degas provided an antecedent for zooming perspectives and radical cropping, Vallotton’s (1865–1925) life-size study of a woman’s buttocks still manages to surprise, with its daring framing and unusually focused subject matter. Information about the model from above the waist and below the thighs, along with details of setting, is excluded in lieu of lavish attention to every physical feature of the buttocks and upper thighs. Like Courbet’s equally abbreviated Origin of the World, this work was not intended for public exhibition. While it is certainly a worthy display of the artist’s technical skill and powers of observation, it also stands as a portrait of sorts. One might consider Edmond Duranty’s words from The New Painting (1876), in which, although he was writing about the Impressionists, he remarked that "by means of a back, we want a temperament, an age ... to be revealed ... by a gesture, a whole series of feelings." While Vallotton only shows a fragment of the whole, this voluptuous synecdoche conveys a sense of personality through the insouciant tilt of the hips, resulting in ample wrinkles and dimples of fleshiness, and in the hand on the left hip just visible at the upper left corner.

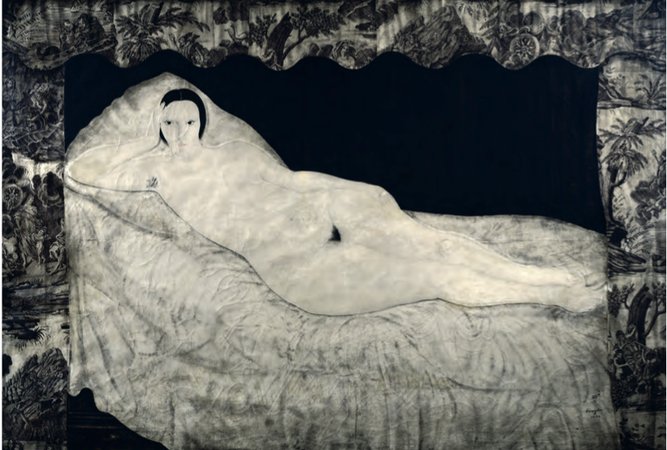

RECLINING NUDE WITH TOILE DE JOUY

Tsugouharu Foujita

c. 1922

Tsugouharu Foujita (1886–1968) was born in Tokyo and studied at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts before moving to Paris in 1913. He embraced the city’s eccentric and bohemian lifestyle, sometimes even donning a lampshade as a hat. Enlivened by artists such as Matisse, Picasso and Modigliani, he developed a unique style that blended traditional Japanese techniques with the ideas of the French avant-garde. His method of drawing delicate black outlines on white, porcelain-like paint, for example, simultaneously recalls the simplicity of line in Japanese woodblock prints and the relatively new art of photography. In 1922 Foujita created a series of nudes loosely inspired by Manet’s Olympia and the odalisques of Ingres. His subject here is the glamorous Kiki de Montparnasse, queen of the bohemian set and muse to numerous artists of the period. Her pearl-white skin, created in enamel paint and outlined in black, is almost subsumed by the diaphanous folds of the bedclothes, and unlike Olympia she gazes out past the viewer, framed by toile de Jouy curtains. The ornate and traditionally French printed linen fabric is juxtaposed with the sitter’s alabaster skin and black background, and alludes to the erotic sensuality that can lie beneath the most quotidian surface.

BLUE NUDE III

Henri Matisse

c. 1952

This is one of a series of four nudes that Matisse (1869–1954) made in the spring of 1952, each a simplified silhouette in blue showing a woman with her arm crooked behind her head, her left foot curled under the bend of her right leg. Small separations between the patches of color suggest depth, setting up a dynamic relationship between figure and ground. The nudes were made using a radical technique that Matisse invented in the 1940s called papier découpé ("paper cut-outs"). Large sheets of paper were painted by his assistants in single shades of gouache paint. Once the sheets were dry Matisse would cut them into shapes before his assistants, under his instruction, fastened them to the wall of his studio with pins, positioning the painted paper in the patterns he desired. The cut-outs answered one of the central questions of Matisse’s artistic life: how to seamlessly combine line with color. They allowed him, in essence, to "draw" directly into the color in a process he described as "painting with scissors". The cut-outs re-energized him in his final years when, after a botched operation and with failing eyesight, he was confined to his wheelchair and bed. Engagingly simple yet subtly sophisticated, they reinvigorated his lifelong interest in the female body.

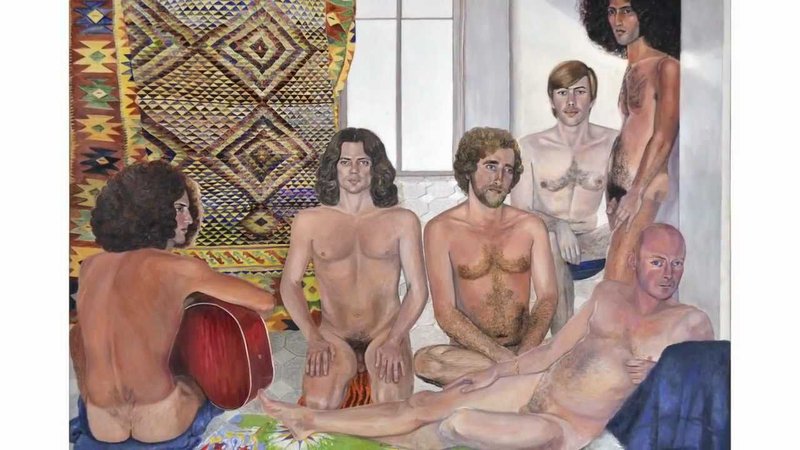

THE TURKISH BATH

Sylvia Sleigh

c. 1973

Inspired by the Women’s Art Movement, which sought to highlight and counteract stereotypical representations of women in art, Sleigh (1916– 2010) painted a series of works that reversed accepted traditions by featuring nude men in poses that were more commonly associated with female models. The Turkish Bath is a gender-reversed version of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Le Bain Turc (1862). Instead of almost identical and voluptuous harem nudes, Sleigh depicted a group of naked men, each with different body shapes, hair, ages and ethnicities. These variances ensured that in sharp contrast to Ingres, no one body type was fetishized. Indeed, all Sleigh’s characters were recognizable as friends and colleagues in the New York art world of the time. The artist was concerned that turning male nudes into art subjects should not simply duplicate the kind of objectification that women experienced throughout art history. She spoke of "portraying both sexes with dignity and humanism" and chose their poses carefully to avoid humiliation or overt sexual invitation. Indeed, in contrast to Ingres’s reclining, daydreaming bathers, Sleigh’s models are alert and look directly at the viewer, challenging us to look at them.

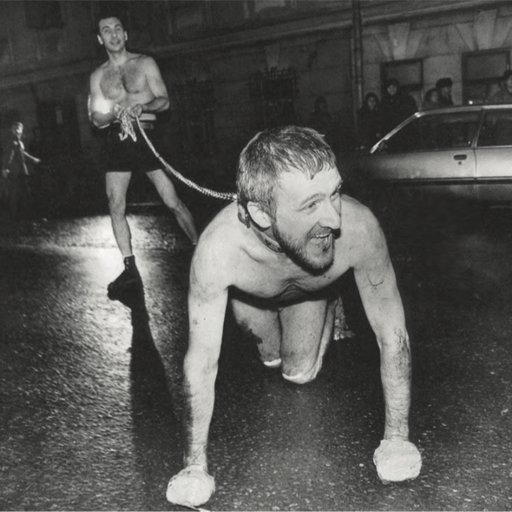

LAUGHTER DURING THE 7TH SURGERY–PERFORMANCE N°1, OMNIPRESENCE

Orlan

c. 1993

When the radical French artist Orlan (b.1947) suffered an ectopic pregnancy in 1978, she decided to film the surgery it engendered and remain conscious throughout. The incident inspired an ongoing series of performances using her flesh as a medium, turning herself into a living sculpture. Videotaping her cosmetic procedures, Orlan identified her approach as Carnal Art and reincarnated herself as ‘Saint Orlan’. Carnal Art, as defined by Orlan in her manifesto, "is self-portraiture in the classical sense, but realized through the possibility of technology ... it transforms the body into language". Referencing art history, Orlan reshaped her face according to the ideals of historical beauty: her mouth became that of François Boucher’s Europa; her chin, Botticelli’s Venus; her forehead, Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. By transplanting symbols of beauty onto her face, Orlan deconstructs the notion of the feminine as a stable category. Throughout her surgeries Orlan drew with her own blood and read poetry and theory, thereby refusing to be passive at any point during her own saintly transformation.

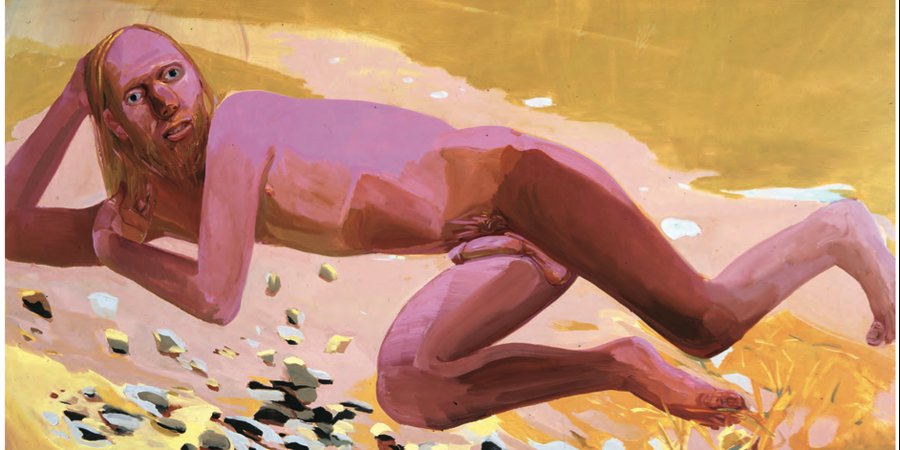

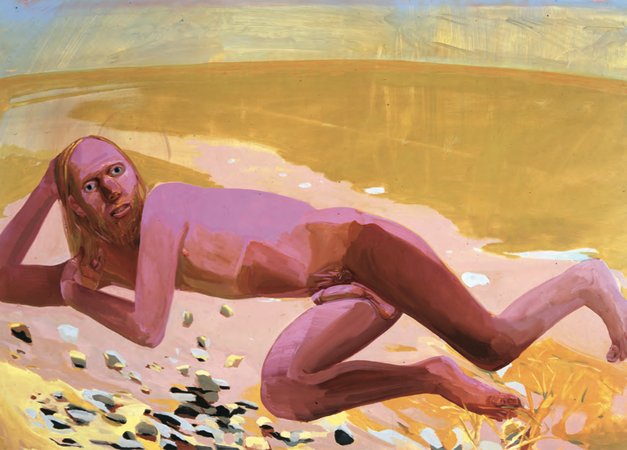

RECLINING NUDE

Dana Schutz

c. 2002

This painting is just one scene from a series of post-apocalyptic scenarios dreamt up by Dana Schutz (b.1976), called "Frank From Observation." Frank, a fictional subject, is the last man on Earth, and Schutz the last remaining painter (and woman). Stretched out on a beach, sunburnt pink, scruffy and obliging, Frank poses like a pinup, yet his sexuality is somehow benign. Despite being the only surviving specimen of masculinity, in his isolation he is emasculated. By inventing a world where Frank is her only subject, and by extension her only available muse, Schutz subtly subverts the tradition of the reclining nude, in which women have historically been painted as passive, receptive and suggestive odalisques in service of the male gaze. By taking portraiture back to her own imaginary "ground zero", Schutz makes Frank both model and fool. In his philosophical novel Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883–91), philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche disparagingly describes the "Last Man" as a figure who is tame, mediocre and uninspiring; a man who "lives the longest" and makes "everything small". Under her active and lampooning brush, Frank’s body becomes the property of Schutz – a plaything, the butt of a joke, a Nietzschean loser.