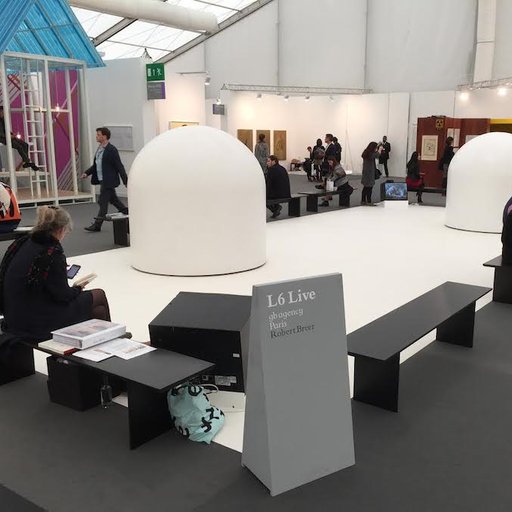

Is it an art fair? Is it an exhibition? Is it even some kind of wacky dealer-curated biennial organized by a few of the coolest (and too-cool-for-schoolest) galleries in the business? Yes to all of the above—but what's important is that the idea of creating an event where galleries can showcase single artists yields an excellent platform for discovery. Here are 10 of the most pleasant, if sometimes initially unsettling, surprises at the fair.

JUNE HAMPER

White Columns

White Columns has an almost uncanny track record of unearthing overlooked artists, either from the recent past or from precincts considered “outside” the traditional art world, and the nonprofit has repeated this service with a display of lovely terra-cotta vessels by someone they found close to home, England’s June Hamper. The 87-year-old mother of Stuckist painter and White Columns championee Billy Childish (born William Hamper), the artist began making pottery in her 50s at an adult education center—leading her deadbeat husband to deride her interest as proof of a “second childhood,” and inspiring her son along the way, who saved some of her best pots. (Many others were lost or shattered, the pieces strewn around her garden.) On view at the fair, her pieces—some of which are collaborations with Childish—are enormously charismatic: ranging from cups to jars to small figurine-type objects, they are sculpted to depict emotive faces, entire people (one with his hands thrust worriedly in his mouth), and haunch-sitting cats, each of which regard the viewer with a timeless solemnity that comes across as strangely ancient. Now in frail health, Hamper hopes to be well enough to create new pieces for a show at White Columns; all of the pieces that were for sale at the fair sold quickly, for between $750 and $1,500.

VIRGINIA OVERTON

Mitchell-Innes & Nash

Amid the fair’s monastically spare layout (the dealers’ chairs, ordained by the architect, looked decidedly uncomfortable), Virginia Overton’s bare-bones architectural intervention at Mitchell-Inness & Nash’s booth came off as refreshingly rough, if conceptually elegant. Built from 120 unaltered pine 12x2 boards stacked in a triangle by a corner window, the piece was the latest incarnation of an installation that was included in her Alex Gartenfeld-curated show at the ill-fated MoCA North Miami earlier this year, where it appeared as a lean-to arranged against the museum’s walls. Overton, who grew up on a farm in Tennessee and is no stranger to the lumberyard, managed to build the piece within the span of a few hours—wowing her dealers, who priced the result at $85,000. Expect to hear more about her site-specific work when she has a solo show at White Cube next year.

AURA ROSENBERG

Martos Gallery

It must be a form of alchemy—Aura Rosenberg can take filthy, raunchy, full-on porn and transmute it into objects of almost decorous beauty. It helps that she’s been at it for a while now. Rosenberg began amassing an archive of vintage material from pornography’s so-called Golden Age of the 1960s and ’70s (when the genre went mainstream, and production values went up to include costumes and sets) and incorporating it into her work in the ‘80s, but then transitioned to other subject matter around the turn of the century when she had a daughter. Now, she and Martos gallery have opted to revisit this fecund period with two bodies of work on view at the fair. For one, Rosenberg painted set pieces from porn films on sheets of golden paper, and the exquisiteness of her tiny brushstrokes, the resplendence of the light effects (thanks to the gold under-layer), and the cool remove of the compositions recall the arcadian scenes of Poussin. Then, on the ground, is a circular scattering of rocks of different sizes—think Robert Smithson, or Richard Long—each of them affixed with a pornographic close-up and coated in resin. Originally created in the ‘90s as props for photographs (she would put them in streams, and once arrayed them in a Grand Canyon vista), the rocks can be displayed outside, and are being offered at $25,000 as a single piece; the paintings are $9,000 each. Shown at NADA last year, the rocks are sensational, and the good news is that Rosenberg has recently resumed making them, for an upcoming show in Düsseldorf.

HAROON MIRZA

Lisson

Haroon Mirza’s sound installation feels a bit like what might happen if you converted a bug zapper into a nightclub. Set up in a small darkened room, with jagged multicolored soundproofing foam lining one wall, it features eight electrical components that flare to life: one string of LED lights surrounds a window, one crawls across a wall, a speaker is embellished with a handful of tuppence coins in its upturned cone, and a flatscreen TV, a vintage telephone, and an old radio sit on a table. The first thing a visitor notices is that each component is hooked up to an amplifier, which broadcasts the sound of the device turning on—the “zzzt” of the blue LEDs at one frequency, the boom and jangle of the coin-filled speaker, etc. The second thing you notice is that they’re actually playing a catchy, beat-driven song, which turns out to be “Access,” a piece of Acid House music by DJ Misjah. Governed by a circuit board that Mirza coded and implanted in the TV screen, the piece (£65,000) lasts seven minutes, and is unexpectedly addicting—the best way to experience work by the artist, who won the Silver Lion at the 2011 Venice Biennale, since his New Museum show last year. Mirza's star continues to rise, for good reason, and next year he’ll receive a solo show at Basel’s Museum Tinguely during Art Basel as well as a survey in Madrid.

PREM SAHIB

Galleria Lorcan O’Neill and Southard Reid

The 32-year-old London artist Prem Sahib makes minimal, materially precise, conceptual works that typically reference his city’s underground gay culture, but in the subtle lingo of cruising. For instance, a trio of roughly person-sized pillars covered in white tile (the type used in public bathrooms) are called Watch Queens, evoking to the slang term for men who either like to watch others have sex or who watch out for the police while others have sex in public. Another piece, 11 Hands by 10 is a large black mat on which three black, laptop-suggesting sculptures are placed, and it stems from a plastic bed that the artist encountered in a dark room in a sex club that he used his hands to measure in the dark (hence the title); the laptop sculptures suggest a domestic scene, conflating the anonymity of the sex club with the familiar intimacy of the bedroom, the hardcore with the loving. The pieces are priced at $20,000 for the bed and $10,000 for the pillars, and Sahib is on the verge of a busy year, with shows upcoming at Southard Reid in London, Lorcan O’Neill in Rome, and the Breeder in Athens.

MATTHEW CERLETTY

Jay Gorney

A painter of sedulous care and terrific skill, Matthew Cerletty applies his talents to what often amounts to cliché imagery, hoping to make his viewers delve more deeply into something they would otherwise experience as ignorably one-note. His technique was on compelling display at the fair, where lingering looks were slowly rewarded. One painting of snakes writhing against a monochrome background gave way to a study in tactility—the cream-colored background was applied with a toothbrush, providing for a grainy, almost 3-D surface, while the snakes were as cool and crisp as if they were laser-printed (they were not). A ghost, meanwhile, becomes a Rothko-esque pulsing dialogue between figure and ground, and its purple background reveals itself to be a perfectly modulated gradient, going from dark to light in whisper thin bands of paint running down the canvas, again in a way a computer would envy. His paintings at Independent range from $22,000 to $35,000, and the ghost sold.

NICOLAS DESHAYES

Jonathan Viner

Another young British artist with a knack for using materials drawn from public spaces, Nicolas Deshayes works with the technicians who create the vitreous-enamel-on-steel signage for the London tube and then overlays the hefty forms with flat images of people walking or waiting or doing other things one might do while in transit—or, in other pieces, with abstract flows of red paint that suggest blood coursing through veins. This parallelism between the different circulatory systems, those out in the cities and those inside our bodies, is a core theme for the 30-year-old artist, who previously created a body of work around the fact that the fat from the food restaurants in London’s SoHo neighborhood dispose of congeals into giant uncanny masses clogging the sewers below. At the fair, the vein pieces were priced at $9,000, the other works at $12,000, and it amounted to a rare New York showing for the artist, who has only appeared in two group shows in the city, but who has shows at South London Gallery and Tate St. Ives coming up, and who just finished a residency at the Zabludowicz Collection's Finland outpost.

YVES KLEIN

Dominique Lévy

If you haven’t already heard about the most talked-about piece at Independent Projects, then—spoiler alert—you may want to experience it yourself before reading this. Here’s my experience of it: I walked into the booth and saw a large white box on a narrow pedestal, about chest-high, with a circular aperture leading to a dark velvet sleeve into the interior, and I was told to put my hand inside. What I felt was a surprisingly warm, slightly moist, smooth, and oddly squishy horizontal bar, and as my hand traveled from that part to a slenderer vertical that was covered with what felt like wispy hairs. I withdrew my hand quickly, reached back in to experience the mysterious bars again, and then told my friend that she had to put her hand in too because it was just too weird and unsettling. She did and, after a few moments, let out a yelp, saying that something had grabbed her. Indeed something had, and it was the naked man who was sitting in the box (a rock-climber, doing shifts with a female yoga teacher), performing in Sculpture Tactile, an artwork that Yves Klein conceived in 1957 but never realized, thinking it to be too radical for the art world of the time; he then died of a heart attack before the world was sufficiently prepared, so the work’s appearance at the fair, a collaboration between the artist’s estate and Dominique Lévy curator Begum Yasar, was its world premiere. Available for sale only to a museum, it was an arresting, economical, and avant-la-lettre riposte to Marina Abramovic’s current much-ballyhooed “Generator” show.

Somewhat macabre in appearance, Paulina Olowska’s sculpture at the Metro Pictures booth is a layer cake of historical reference points—it’s based on a collaboration that Isamu Noguchi and the choreographer Martha Graham did in 1946, where the sculptor created a starkly pared-down tree-like sculpture that the dancers would encircle, letting their clothes get tangled in the branches. Here, Olowska created a sculpture inspired by Noguchi’s and then draped it in the black cloth that was Graham’s signature, a homage to the kind of performance that the artist has been exploring in her work since the days she ran Nova Popularna, an underground bar and performance space she opened in Berlin with Lucy McKenzie in 2003. With solo shows at the Kunsthalle Basel and the Stedelijk last year under her belt, Olowska is poised to take over Tate’s Turbine Hall next year. The sculpture was priced at $85,000, while surrounding collages that were informed by puppet performances were $25,000 apiece.

DAN ATTOE

Peres Projects

A classic, full-on painter of the old-school variety, Dan Attoe got his big break when an assistant of Javier Peres who had gone to the University of Iowa told the dealer that one of the graduate students she had studied with was terrifically talented, and very good-looking. Peres visited, bought a year’s worth of his paintings, and has represented him ever since. Looking at the canvases, you can see why they’re so persuasive: lush scenes populated by tiny figures and made ominous by offbeat David Lynchian touches, they recall the paint handling of the Northern Renaissance, with light seeming to emit from their surfaces. Attoe always includes text in some fashion, though it can sometimes be difficult to make out, since he sometimes does his filigree work with a brush of only two hairs. (Vermeer, legendarily, was able to go down to one.) This is the artist’s first showing at an art fair, and all the works ($30,000 for bigger ones, $15,000 for smaller ones) sold out, leading Peres to conclude it’s time to raise his prices.