EXPO CHICAGO, now in its fourth edition, has expanded to showcase more galleries than ever before. At the same time, this year's fair is also presenting a tighter mix of top-quality contemporary art. Here are a few standouts that you should know about.

DEAN LEVIN

Rendered Memory Painting #2 & Rendered Memory Painting #1 (2015)

Marianne Boesky Gallery (New York)

$7,500 ($6,000 for smaller one in the back room)

In the back room

In the back room

A rising star in New York, Dean Levin is known for his abstract canvases that attempt to bridge painting and architecture by wrapping around corners or standing erect in tower-like cases that he places in the center of a room. In a new body of work, he’s tackling the built space within the picture plane. Called “Rendered Memory” paintings, these pieces—which he first debuted at Boesky East earlier this year—consist of a digital rendering of a gallery space which the 27-year-old artist “singes” onto linen with a laser printer and then paints over with translucent brushstrokes that confuse flatness and perspective. At EXPO, Boesky had a trio of paintings derived from a room in Los Angeles’s Kohn Gallery (where Levin will have a show in January). In these works, his process produces a timeless effect: the swirling brushstrokes could be the winds of antiquity blowing through one of Tintoretto’s Venetian archways.

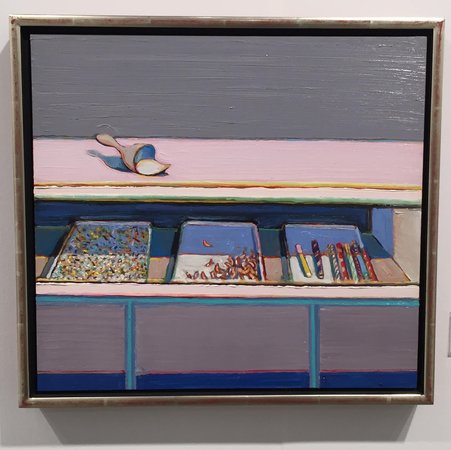

WAYNE THIEBAUD

Candy Trays (2010) and Burger and Fries (2014)

Paul Thiebaud Gallery (San Francisco)

$1 million+

There’s a common misconception that the great American painter Wayne Thiebaud only worked on his iconic tributes to cakes and other cavity-inducing soda-shop delights during his glory era of the 1960s and ‘70s, before moving on to focus on his Bay Area landscapes. But no, Thiebaud never fully abandoned comestibles as a subject matter, and now at 95 he continues to render heartland delicacies in the same luscious way: always deriving the compositions from his imagination (and not observation), and placing his emphasis not on the food porn but on classical considerations of shadow, light, scale, color, and perspective. The only thing that has changed, as he goes to the studio every day to work (between his habitual thrice-weekly games of doubles tennis) is that his treatment of color has become less naturalistic and more lyrical and virtuosic. At the fair, showing at the gallery of his late son (who passed away in 2010), are two of these recent paintings—a rare opportunity to collect an artist whose truly first-rate work hardly ever comes up at auction.

MICKALENE THOMAS

QuanikahGoes Up (2005)

Kavi Gupta Gallery (Chicago)

$20,000

Mickalene Thomas at EXPO CHICAGO

Mickalene Thomas at EXPO CHICAGO

When Mickalene Thomas was at Yale a little over a decade ago to get her MFA, she had already landed upon her subject matter: identity and representation of the self, channeled through the ideas of artists like Cindy Sherman and Adrian Piper as well as the outsize personae of figures like Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, and Eartha Kitt. Now she uses other black female figures as her stand-ins, but back in her school days she posed in all of her own pictures—playing a series of different characters, all invented. “I was a better actress than some of the women I work with now because I knew exactly what I wanted to portray with the role,” she told Artspace. But after eight years or so, she recalled, “it became a problem looking solely at myself in my work—it was a little too much to bear on my shoulders psychologically." She began to train her camera on other women, and then gradually focused on her mother, who yielded some of her most famous portraits. At the fair, Kavi Gupta brought one of Thomas’s pieces from her thesis show (the entirety of which was shot either on 35-mm film or with disposable cameras). It depicts her character Quanikah attending her first day at Yale, full of possibility and intent on “discovering her own beauty.”

CHRISTOPHER RAUSCHENBERG

Marché aux Puces, Saint-Ouen (2008)

Laurence Miller Gallery (New York)

$3,000

Did you know that Robert Rauschenberg had a son (through Susan Weil, an artist he was married to briefly in the ‘50s), and that Rauchenberg fils is an artist too? In the photography world, this is common knowledge. Christopher Rauschenberg, highly active in the Portland art scene where he also runs Blue Sky Gallery (as well as his father’s enormous foundation), has spent decades traveling the world to take pictures of foreign locales as well as artist studios (including those of Robert Frank, Chuck Close, and his dad). At the fair, Laurence Miller Gallery is showing one from the artist’s “Found Object” series, in which he captured still lifes from the flea markets just outside of Paris.

ELIZABETH NEEL

Response to the Tide & Love and Syntax (2015)

Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects (L.A.)

$38,000 apiece

Another artist whose genes have choice art-historical provenance is Elizabeth Neel, the granddaughter of the legendary portraitist Alice Neel. The 40-something descendant hasn’t fallen far from the tree in terms of medium, but her approach represents quite a divergence. An abstract painter to the core, Neel draws on the macho legacy of gestural Abstract Expressionism while cross-pollinating it with a highly deliberate and strategic system of mark-making. To create her large-scale pieces, she lays unstretched canvas on the floor of her Brooklyn studio (à la Pollock) and then attacks it with sweeping brushstrokes, taped-off geometrical passages, and Rorschach-like splotches (made by allowing paint to pool and then folding over the canvas with a tight crease). With big stretches of canvas left empty, the results have plenty of fireworks but retain a light touch.

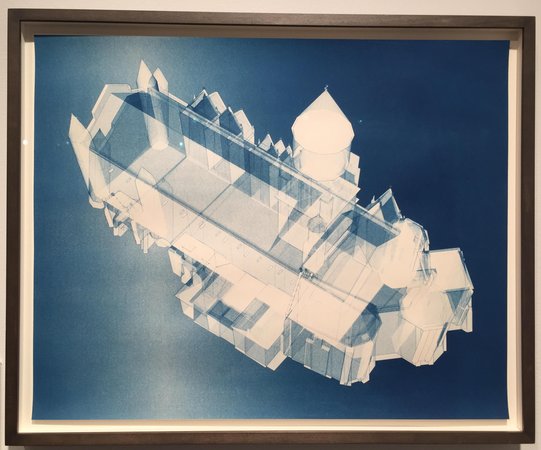

JOHN HOUCK

From the “Echelon” series

Aperture Foundation (New York)

$2,500

John Houck became a sensation among collectors a few years back when he started making trompe l’ceil photographs by folding, photographing, and then re-folding abstract compositions, so that the real and captured creases created a perceptual tension. But before that, the young Whitney ISP graduate—who has shown with Gagosian and Hauser & Wirth, and is represented by On Stellar Rays—carried his interest in re-photography into more representational terrain. For an older body of work on view at the fair, Houck downloaded architectural renderings of Gothic cathedrals from a site called 3D Warehouse and inverted them to negatives, eventually printing them as cyanotypes. These beautifully composed images accomplish another inversion in the form of their perspective: while the builders of these hulking edifices designed them to be admired by viewers looking up from the ground, the artist presents them as a view from on high—or at least from the helicopter cameras he witnessed as they panned the buildings during a commercial break from the Tour de France.

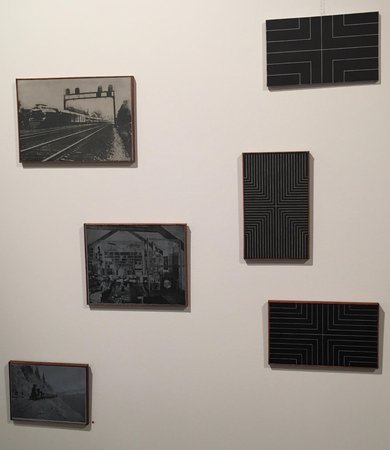

RICHARD PETTIBONE

Paintings after Frank Stella’s “Black Series” (1966), Katherine Dreier’s Living Room (1966), & Untitled (Train) (c.1960s)

Hollis Taggart Galleries (New York)

A Duchamp obsessive, Richard Pettibone famously twisted the Frenchman’s readymades in the 1960s to accommodate not only commercially produced objects but also fully realized paintings—paintings by peers like Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns that were barely dry by the time Pettibone copied them. Often much smaller than the originals, these homages are irresistible collectors’ items; the three ersatz early Frank Stella paintings at the fair are certainly no exception. Joining them is a painting Pettibone made of a photo of the living room of Katherine Dreier, the avant-garde Société Anonyme co-founder, collector, and patron of Duchamp; there’s also a painting of a train, another fixation of the artist’s.

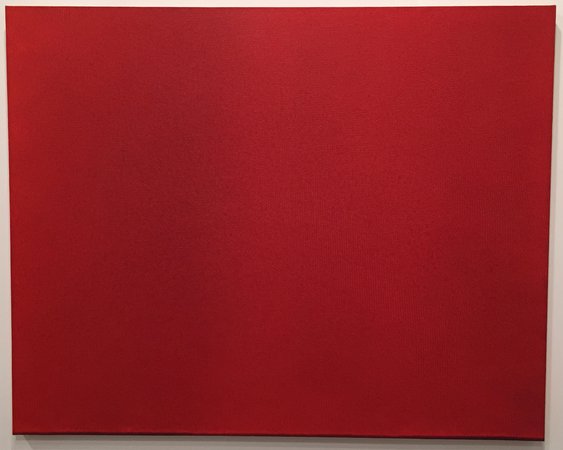

CAROL BOVE

Fifth Red Sweater Painting (2015)

David Zwirner (New York)

$105,000

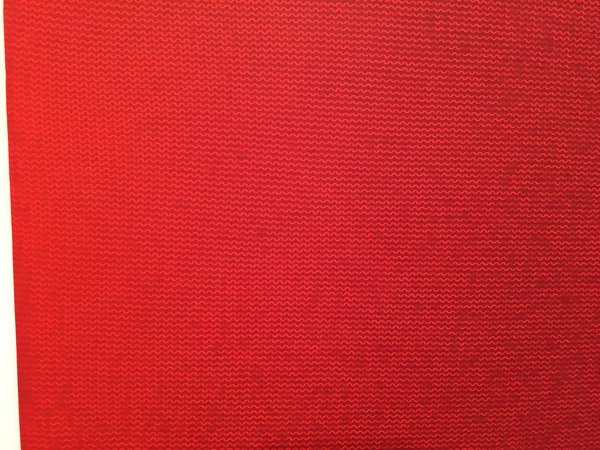

A detail of the painting

A detail of the painting

Because EXPO is known as a place for the Midwest’s curators to hunt for upcoming exhibition fodder, the folks at David Zwirner made sure to bring a slate of first-class works by artists ranging from Isa Genzken to Flavin and Judd. This one was a dazzler. Could that actually be a Carol Bove? Indeed it is, from a brand-new series that the sculptor—who has made paintings of nets and peacock feathers in the past—creates by laying down rows of yarn on a red-painted canvas and then applying another, darker layer of red on top before removing the threads. The concept may be slender, but the effect is sensational; the result is a tribute to Modern pioneers like Agnes Martin, one that also recalls the knitted paintings of Rosemarie Trockel.

ROBERT GOBER

Untitled (1992-93)

Matthew Marks (New York)

Around $100,000

On the eve of his seminal 1992 show at the Dia Art Foundation (then in Chelsea), Robert Gober made a wedding dress by hand and stepped into it, donning a wig and smiling for the camera. He then embellished the photo to look like a bridal-attire ad for various department stores and inserted it into one of his dozens of handmade replicas of the New York Times—often directly below an article about the oppression of gays in America. These works were the heart of the Dia show; they were placed in stacks around the gallery space against the backdrop of his woodland wallpaper and his mute, solemn sinks. Today Gober's poignant intervention is made even more meaningful by its place in history; it was created precisely 20 years before the Times allowed announcements for gay marriages to run in its “Vows” section. The dress itself is in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, but this original photo comes in an edition of 15.

THEASTER GATES

White Cube (London)

$165,000

Theaster Gates signing his new Phaidon book at the fair

Theaster Gates signing his new Phaidon book at the fair

Theaster Gates has been having a hell of a month. His extraordinarily ambitious Stony Island Arts Bank opens this weekend on Chicago’s South Side, and he has been at the fair signing copies of his just-released definitive monograph from Phaidon. Halfway across the globe, meanwhile, his work is a centerpiece of the Istanbul Biennial. In Istanbul, Gates set up a pottery studio and dedicated himself to copying a 17th-century Iznik dish in the effort to internalize Turkish tradition—an kind of Method-esque immersion through clay, which the artist, who trained in Japan as a potter, has long considered his first true medium. Lately, however, Gates has begun to rethink that assessment. After all, isn’t tar—the substance he helped his roofer father spread atop buildings as a teenage apprentice—an even truer first medium, with the smears of tar prefiguring his first stroke of a paintbrush? The realization sparked a new body of work fusing these two lineages, and an example is on view at White Cube. Atop a plinth of reclaimed timber stands a tall clay pot, sheathed entirely in tar.