Sascha Braunig ’s paintings thrive on a multiplicity of uncanny forms and forces: they play with light and shadow, flexibility and rigidity, fullness and emptiness, push and pull. These dynamics are made to negotiate with one another on the flat linen-covered board on which she paints. Braunig is a master of the trompe l’oeil , her visual effects ranging from the creation of depth and perspective to fantastical bodies, lighting and even movement, all rendered with carefully synchronized color palettes.

Sascha Braunig,

Warm Leatherette

, 2015. (Courtesy of the artist ad Foxy Production. Photo: Johan Blommaert.)

Sascha Braunig,

Warm Leatherette

, 2015. (Courtesy of the artist ad Foxy Production. Photo: Johan Blommaert.)

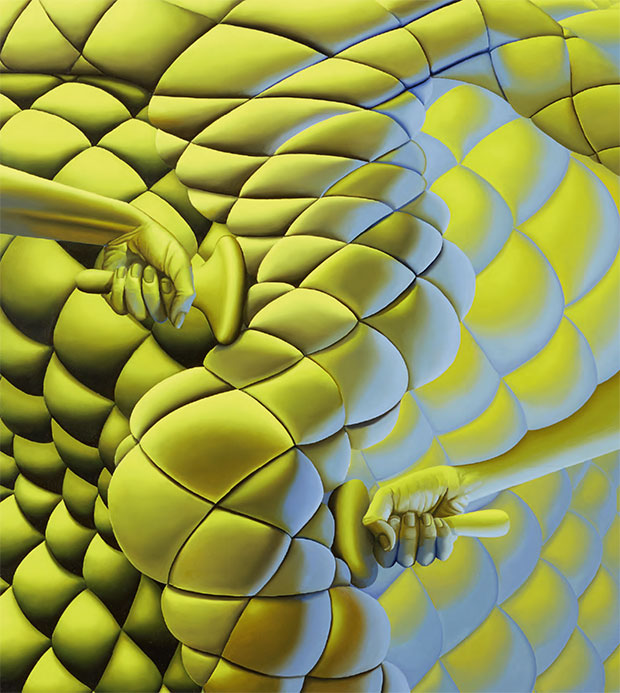

In Warm Leatherette (2015), a sinuous form covered in quilted material snakes across the centre of the image against a matching background. Careful contouring gives the impression of the leatherette being wrapped around bulging flesh or packed wadding, its folds offering an opportunity for intense light-and-shadow effects. A pair of forearms with finely detailed hands pushes stylized burnishing tools into the quilted body, apparently working it into a more curvy shape. Painted in bilious yellow, the subject is lit by raking light which causes bluish grey highlights and deep black shadows. It has a vivid luminosity, which produces a kind of visual giddiness in which the eye attempts to capture the combination of form, color and suggested movement at play in the image. Although Braunig ’s aesthetic and lighting effects share a smoothness with digital imagery, she paints from "life," making small clay models for her subjects and illuminating them in her studio with bright lamps and colored gels "inspired by over-the-top movie lighting."

Sascha Braunig,

Saccades

, 2014 (Courtesy of the artist and Foxy Production. Photo: Mark Woods)

Sascha Braunig,

Saccades

, 2014 (Courtesy of the artist and Foxy Production. Photo: Mark Woods)

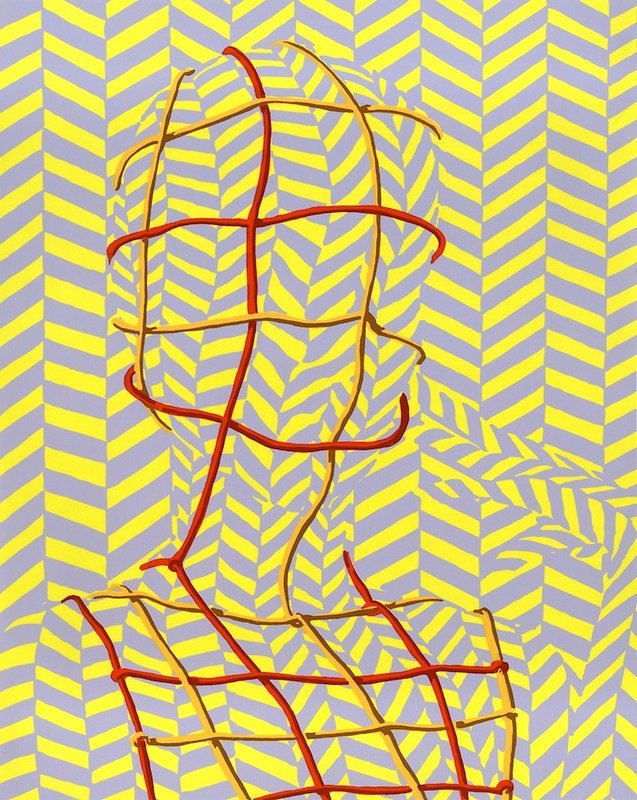

The winding form in Warm Leatherette performs the contrapposto of classical statues or the popped hip of contemporary fashion models. Braunig has said she is interested in the way "the female body is perpetually abstracted, reduced, distorted, or compared with inanimate objects" in art and culture. Her paintings take up this concern, with forms that allude to female bodies, but also suggest the possibility of evolved species. Saccades (2014), titled after the term for the rapid motion of the eyes between fixation points, depicts a form resembling a human head, made of pearls or white beads, set against a background made of the same stuff. Rifts and protrusions in the head’s surface hint at facial features but ultimately, the portrait remains blank. Braunig has described her subjects as "Ur-characters" and "portraits of a state of mind or a potential state," but words don’t seem up to the task of defining these states, and whatever they are is best expressed by the paintings themselves.

Sascha Braunig,

La Maitresse

, 2015. (Courtesy of the artist and Foxy Production. Photo: Luc Demers)

Sascha Braunig,

La Maitresse

, 2015. (Courtesy of the artist and Foxy Production. Photo: Luc Demers)

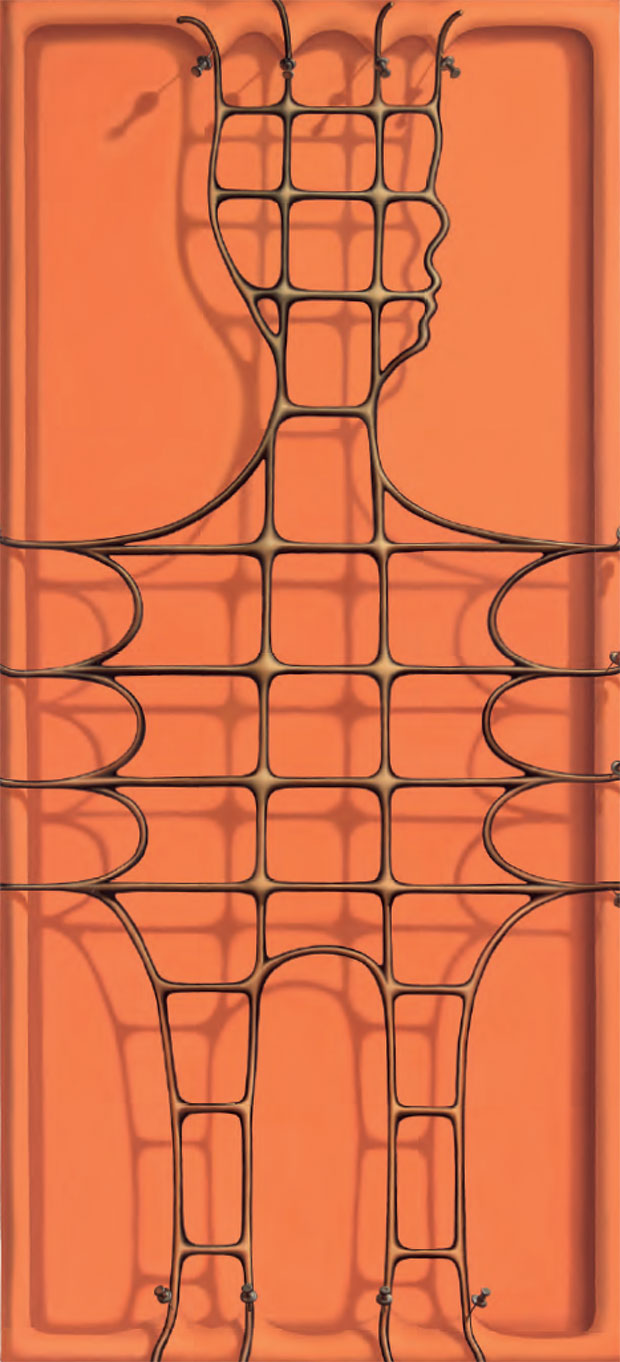

In La Maitresse (2015), Braunig differentiates the figure from its ground, painting the optical illusion of an anthropomorphic mesh silhouette stretched over a frame. The rubbery webbing, a humanoid form voided of any fleshy matter, casts a shadow on the orange ground while its surface gleams in the stark lamplight. It seems almost alive, vibrating with the strain of being pinned so tightly and threatening to escape its confines by flinging itself far away. For Braunig , the ambiguity that surrounds the vitality of her subjects is an essential part of her work, as she explains: it is "important that there is a tension between their lifelessness and possible lifelikeness."

– Written by Ellen Mara De Wachter, excerpted from Phaidon's Vitamin P3 .

Mat Smith: Who are you?

Sascha Braunig : I’m an artist from Canada, currently living and working in Portland, ME, and for the next year, Brooklyn, NY.

What’s on your mind right now?

Most pertinent to this interview, I suppose, is the ever-present question of ‘how to proceed?’ I finished a show a couple of months ago, and now I’m generating new imagery about bodies ensnared or intermingling with their frame, the painting. I’ve decided that I want to summon figures that are strong, flexible, and resistant right now. I’m usually listening to audiobooks while doing the "execution" tasks of painting, and I’m currently in the thrall of Octavia Butler’s “Lilith’s Brood” trilogy. Her insistent themes include interspecies sex, infinitely regenerating flesh, flesh-as-architecture, and the complexity of alliances in any resistance movement. I’m into it, and thinking that these ideas are likely seeping into the images I’m making.

Sascha Braunig's

Big Nets

(2013) is available on Artspace for $550

Sascha Braunig's

Big Nets

(2013) is available on Artspace for $550

How do you get this stuff out?

Well, at the moment, I draw in a sketchbook, then test out ideas and colors with water media or oil on paper before starting a painting on panel. That part is more involved: I often paint from observation of small models, so sometimes I then set about creating a little tabletop stage set—a fantastical scene in three dimensions—as best I can. This model doesn’t look much like the painting—it’s a reference that I expound upon.

How does it fit together?

What the work’s about and how it’s made don’t necessarily fit together. The observational practice has been important because it does change how the paintings look, making them more "graspable." It has also brought me around to making sculptures on a few occasions.

What brought you to this point?

This question is tricky because it assumes that I'm at one point, like a sharpened pencil, whereas I feel more like I'm spread across multiple points like peanut butter.

Sascha Braunig's

Slats

(2012) is available on Artspace for $600

Sascha Braunig's

Slats

(2012) is available on Artspace for $600

Can you control it?

I probably have some control issues, which is likely why I’ve become sort of a precisionist painter. More and more, I’m learning to steer the execution part—painting techniques—but of course you cannot really control when and how your ideas appear, and sometimes you must learn a new technique to execute a new idea. It would make for a boring life in the studio to achieve total control over your materials. As for ideas, you can set up ideal conditions for ideas to appear by reading, looking, and focusing, but to indulge in a cliché: you cannot force them.

Have you ever destroyed one of your paintings?

Yes, because sometimes they’re no good, and there’s a risk of contamination!

What’s next for you, and what’s next for painting?

I’m moving to New York for the year because I’m lucky enough to have been selected for a studio at the Sharpe Walentas Foundation. I hope to keep working with bronze casting, which I’ve started to do already on a small scale. Painting is resilient and seems to be in no danger of fizzling out; I think artists across the spectrum will continue to use it for its tactility and its direct qualities.

This interview was originally published on Phaidon.com as part of a Q&A series with painters featured in Vitamin P3: New Perspectives in Painting —a compendium of today's most exciting artists working in the medium.