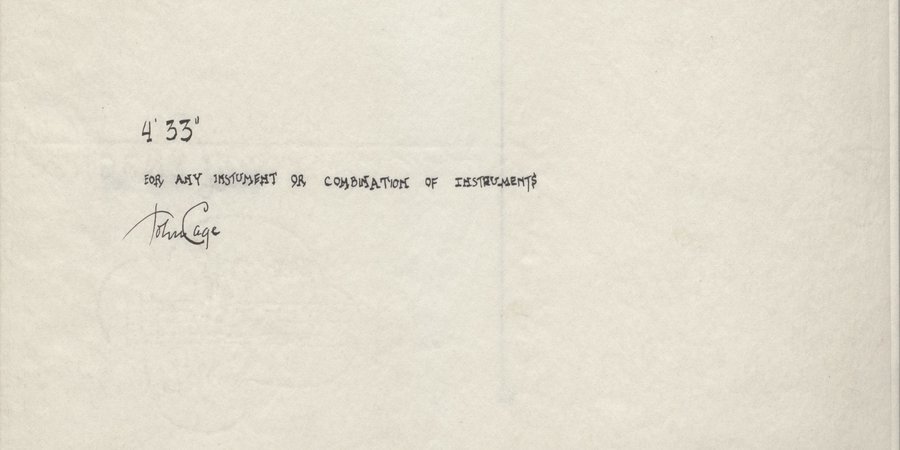

John Cage's seminal piece 4'33'' redefined musical composition when pianist David Tudor sat down to play it in 1952, and nothing happened. Tudor had been instructed to produce four minutes and 33 seconds of utter silence, and that freighted lull—in which the sounds of the audience members, and the street outside, were all that one could hear—changed not only the way people thought about music, but sound art as well.

MoMA recently acquired the score and will be celebrating its achievement on October 12 in "There Will Never Be Silence: Scoring John Cage's 4'33,''" an exhibition showcasing how artists have sought to give artistic voice to the Zen-like, ephemeral work. It comes at a critical moment for sound art, with growing public awareness of the form—helped by Susan Philipsz's Turner Prize win for a sound-art installation in 2010—and growing institutional support lifting it to new levels of popularity. Another show at the Modern, for instance, is "Soundings: A Contemporary Score," the first major exhibition that the institution has devoted to the medium. Then, a short drive outside the city, the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum is concurrently giving over its entire building to "Music," another sound art survey.

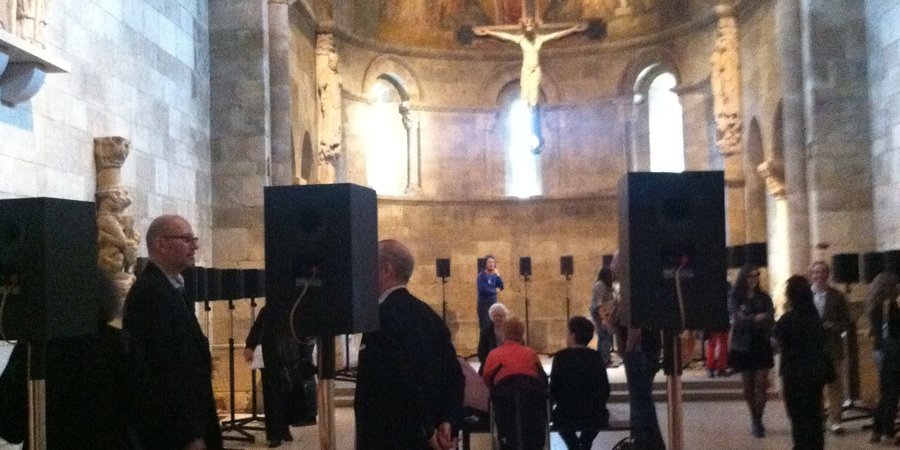

Meanwhile, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's satellite at the Cloisters, Janet Cardiff's Forty-Part Motet (2001) juxtaposes a contemporary work with the medieval surroundings for the first time in the museum's history. Entering the Fuentidueña Chapel, visitors are surrounded by 40 speakers, each playing an individually recorded singer performing a part in Tudor-era composer Thomas Tallis's most famous work. The effect is an overwhelming, multilayered experience with sound.

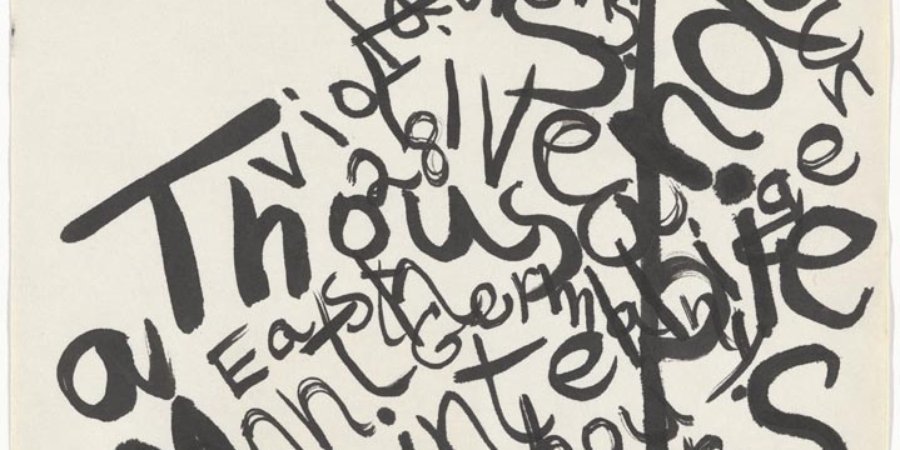

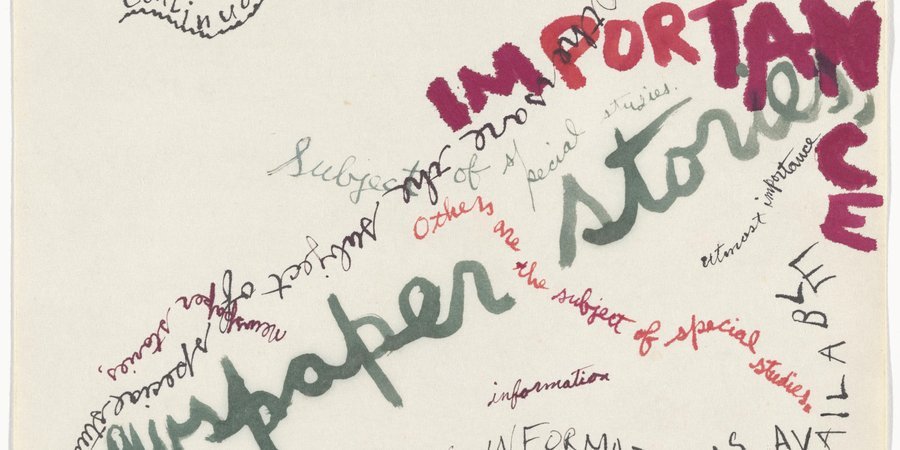

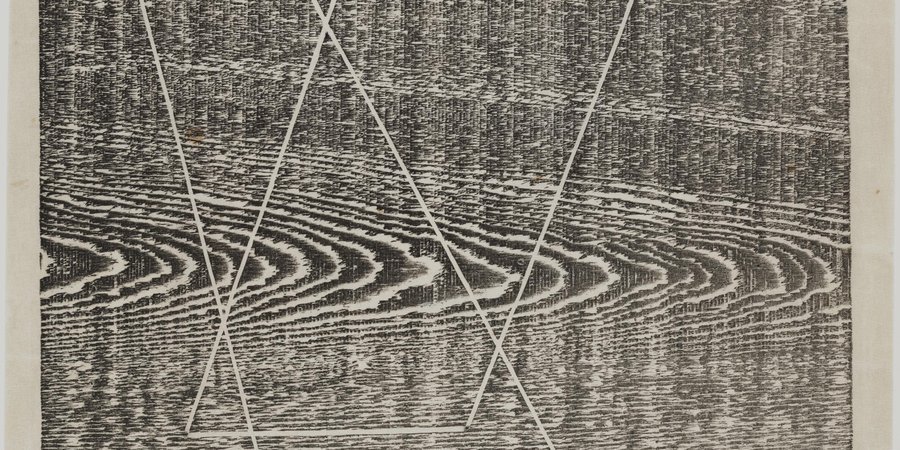

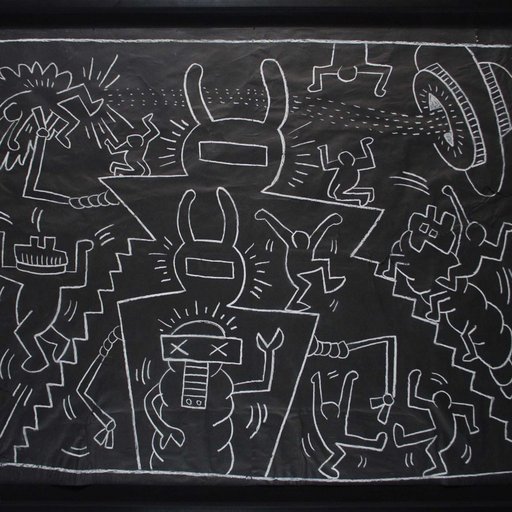

But the spotlight on Cage at MoMA brings light to an important watershed moment that echoes strongly in this fall season—in this case, rendered through visual art. "There Will Never Be Silence" tracks how Cage's radical work activated the imaginations of painters and sculptors, making them reconsider negative space both in terms of sight and sound; Cage thought of silence itself as a structure and clearly took cues from the contemporary art scene of the time. The exhibition features the work of Marcel Duchamp, Kurt Schwitters, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Morris, Lawrence Weiner, and even Andy Warhol, in a mix of artists who presaged 4'33'' and those in conversation with it afterward. A Minimal sculpture by Fred Sandback, of rayon cord demarcating empty space, appeared 15 years after 4'33'' was first performed; Josef Albers's woodcuts clearly skirt the same territory nearly a decade prior.

And the museum has more sounding off on sound to come: the "MoMA Studio: Sound in Space" education series will feature talks throughout the fall. Its Pop Rally concert series takes on the genre as well: next up is Body/Head, the visual artist and Sonic Youth vet Kim Gordon's new electronic duo (her show at White Columns is up until October 19). Last week's edition featured an audio-visual performance by cyclo., made up of the artist/composers Ryoji Ikeda and Carsten Nicolai (Nicolai's work is also in the "Soundings" exhibition). Amid flashing black-and-white distortions on a giant screen in MoMA's atrium, and heavy bass from their set, the duo gave a radical take on how sound art is changing the museum landscape—a fact attested to by the reverb that literally shook the institution's walls.