A massive structure of wooden poles festooned with colorful ribbons by the British sculptor Phyllida Barlow is the first work one encounters when visiting the 2013 Carnegie International, the quadrennial (or thereabouts) show at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art that stands as the oldest global contemporary art exhibition in the United States. The work, entitled Tip (2013), bisects the plaza and obstructs the view of the two permanent sculptures—Richard Serra's Carnegie (1985) and Henry Moore's Reclining Figure (1957)—before plunging against the glass doors of the museum, making for a postcard-worthy approach. Barlow's installation subverts the harmony provided by the relationship between the Serra (which the piece comes within inches of touching) and the Moore, introducing an element of chaos in the public space. In a word, it’s an agent provocateur.

In their excellent exhibition, curators Daniel Bauman, Dan Byers, and Tina Kukielski set out to present a group of works that provokes timely aesthetic questions and reconsiders the role of the giant, money-powered international exhibitions that we have been subjected to for the last few years. Here, sanity and proportion prevails, and it’s a welcome change of pace. But while Barlow's contribution is the largest work in the show, that doesn't mean that the mischief stops there.

In fact, mischievousness lies at the heart of the exhibition. "We love art because it is a troublemaker that changes our thinking, and even our lives," the curators write in their introduction to the catalogue. That brand of trouble manifests itself in a variety of aspects in the International, from the focused and intelligent way it’s rooted in the museum's identity and collection to its engagement with the community to its unapologetic embrace of the human figure. Perhaps as a result, a sense of humor permeates this year's show, along with playfulness and pleasure.

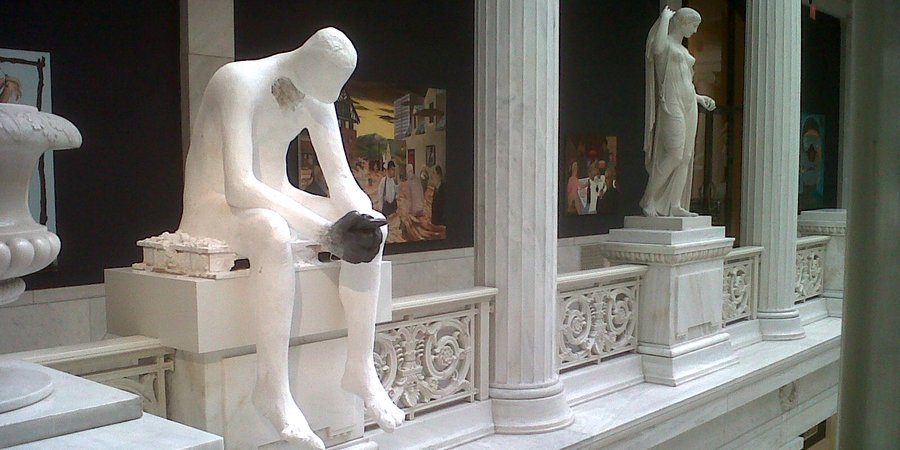

Of the 35 artists in the exhibition, more than half were born in the 1970s or later. Very few of them are high-profile names. Nineteen countries from around the world are represented (although only one artist is from Africa). The curators have made an admirable effort to show artists in depth, giving several enough space for what amount to mini-surveys—Nicole Eisenman, for instance, 19 of whose paintings and sculptures dating from the 1990s to 2011 fill the museum's balcony in the Hall of Sculpture. The winner of this year's Carnegie Prize, Eisenman is widely acclaimed as a painter, but new to sculpture—though you wouldn’t know it from her plaster male figures, which enter into a visual dialogue with the museum's classical collection and indicate that she knows how to capture the sentiments and moods of a fully dimensional human being.

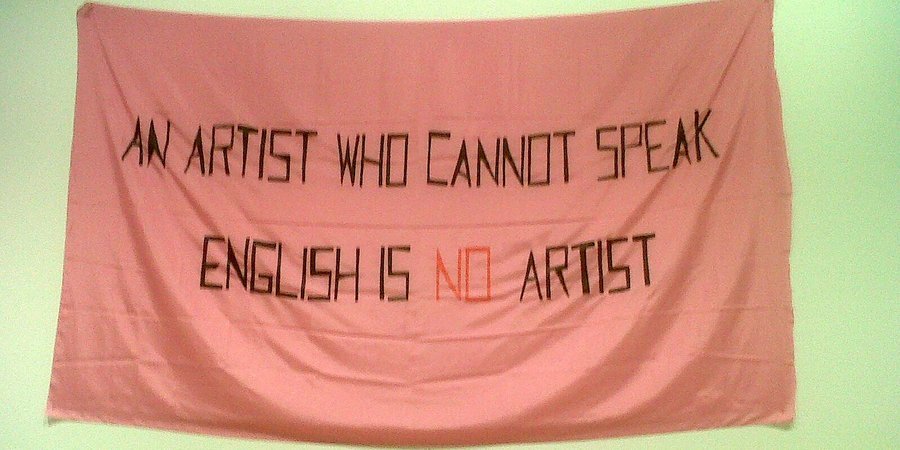

Another in-depth presentation spotlights the Croatian conceptualist Mladen Stilinovíc (b. 1947), spanning 35 years of his artistic experiments in nearly all media. Demonstrating a profound engagement with political activism and the interrogation of power, Stilinovíc’s work combines serious politics with a good dose of leg-pulling, like a banner from 1992 that reads "An artist who cannot speak English is no artist"—a piece he has exhibited in venues around the world—and a series of photographs of himself sleeping, entitled Artist at Work. American artist Rodney Graham's hilarious new photographic light box The Pipe Cleaner Artist, Amalfi '61 dwells on the same subject matter, depicting an artist building small sculptures from pipe cleaners in a quiet and contemplative domestic setting somewhere in the Mediterranean, with the implication that art should be a pleasant rather than stressful activity.

A beautiful wall of 57 drawings by self-taught artist Joseph Yoakum is his largest showing in decades. Yoakum started drawing in his 70s and did one or two drawings a day for the next 10 years—some of them portraits, but mostly landscapes—until his death in 1972. The resulting works are composed of undulating lines and marvelous pastel tones dominated by blues and greens, often forming mountains that rise and rivers that flow into the distance. Looking at these up close is one of the great pleasures of the exhibition: the same colors leap from one drawing to another, merely changing volumes, as they conjure the geographical vistas within Yoakum's visionary world.

China's Guo Fengyi, another self-taught artist, draws with ink on cloth and rice paper, weaving the lines compulsively from the middle and then up and down along the length of the paper. Their course seems to outline the human body, but, seen closely, these eccentric, looping lines reveal a range of recognizable shapes like rivers, waves, trees, and human expressions. Now quasi-obligatory in every major international exhibition, inclusion of such work by self-taught artists has created happy and exciting juxtapositions from which we only can be enriched.

These almost palpable works find an interesting counterpoint with Sadie Benning's 40 hand-cut abstractions in casein and acrylic paint that the artist originally mocked up on her iPhone. Her digitally born forms are a good occasion to give some thought to the relationships between digital and non-digital processes, although this ongoing discussion already threatens to grow old. Similarly, the distinctive and highly acclaimed inkjet-printed paintings of Wade Guyton on the first floor—with a suite of his striking flame canvases shown in a wood-paneled den and another of his stark white paintings on display in a barren, decrepit room—are testimony to this brand of work’s seductiveness and popularity.

Offering an opposite perspective, Vincent Fecteau's mini-survey from the past seven years of a selection of organic handmade and richly colored papier-maché sculptures provide a distinct contrast to the Benning-Guyton tech approach. Along the same lines, the Brazilian artist Erika Verzutti recreates fruits, vegetables, and other objects found in nature as sculptures made of more permanent stuff, like bronze, clay, and concrete. Marked by their luxuriant use of materials, different styles, and incongruous combinations—like an eggshell nesting in a bronze tablet—the objects sit on the floor with an air of nonchalance. Verzutti's vocabulary is flooded with sensuality, and underscores the intimacy between the artist and her object.

A display of work by two Iranian artists born 40 years apart constitutes one of the most brilliant curatorial choices in this exhibition. One of them is film director Kamran Shirdel (b. 1939), who is mainly unknown to American audiences but has influenced a whole generation of Iranian filmmakers. Shooting in the streets and using non-professionals, Shirdel has sought to tell the stories of the people of Iran, and his films—considered subversive—have been banned, confiscated, and censored, with the filmmaker himself blacklisted from time to time.

The other artist is Rokni Haerizadeh, who was abroad when he learned that his work had been seized from a private collection in Tehran. He has since lived in exile in Dubai. Shown on the second floor of the Carnegie Grand Staircase, Haerizadeh's two animations are mesmerizing, along with his works on paper. To create his animations, he hand-paints and draws over thousands of frames of found footage capturing mass-culture subject matter, like the royal wedding of Kate Middleton and Prince William, transmuting it into a delightful visual narrative of his own inspired by the elegant aesthetic of traditional Persian art.

This year the Carnegie’s $10,000 Fine Prize was awarded, rightfully, to the South African artist Zanele Muholi, a self-described "visual activist" who has been photographing black LGBTI communities around the world since 2006. Posing against fabric or industrial backgrounds, her subjects regard the camera with a fierce, forthright gaze. Like Muholi, the American photographer Zoe Strauss has given voice to a specific community—the habitants of Homestead, Pennsylvania, once home to Andrew Carnegie's steel plant. Both bodies of work remain ingrained in the mind long after one has left the exhibition.

Portraiture is also the focus of Californian artist Henry Taylor, whose crude though ravenously observed paintings are populated by African-American subjects, from historical figures like Eldridge Cleaver to people living in his Los Angeles neighborhood. They are placed alongside Sarah Lucas’s twisted and stuffed pantyhose sculptures of body parts in sexually suggestive positions, and reflect the curators’ stated stance that the "figure is still a powerful and relevant tool to confront human experience."

Downstairs, activism meets pleasure in the self-playing musical instruments of Mexican artist Pedro Reyes, the delicate sounds of which contrast with the fact that the instruments are welded from guns—some of them frighteningly large—that Mexico’s military confiscated from drug cartels. The Israeli filmmaker Yael Bartana, meanwhile, tackles the highly politicized topics of her native country through films that examine its cultural and military rituals, as in the case of Summer Camp (2007), which shows an annual display of civil disobedience in which a Palestinian home destroyed by Israelis authorities is rebuilt by a group of volunteers. Home is also the theme of Joel Sternfeld's striking photographic essay on utopian communities—some lost—from the Mojave desert to the hills of Western Massachusetts.

According to curator Tina Kukielski, a museum should embody a micro-history and shelter a memory. Here that also applies to the history of the Carnegie itself, with a particularly delightful aspect of the 56th International being a rehang of the Modern and contemporary galleries that include many participants of past shows, like Willem de Kooning, whose Woman VI (1953) hangs next to Phyllida Barlow's impressive untitled:upturnedhouse ( 2012), a strong tilted cube that waves between sculpture and painting—which in turn duets with Ken Price's compact abstract ceramics next door. It is a pleasure to revisit works by Polke, Baselitz, and Richter (and to be reminded that not long ago this trio was heralded as the brave heroes of New Painting); by the honored conceptualists Fischli/Weiss, Bruce Nauman, and Franz West; and by older artists like Edward Hopper, Charles Burchfield, and Winslow Homer (they were also contemporary once!).

At the heart of the exhibition, fulfilling the promise of Barlow’s puckish installation out front, is a hymn to the spirit of play itself—or, as the curators put it, "play as a way of thinking." This takes the shape of an exhibition within the exhibition called "The Playground Project," curated on the second floor by Gabriela Burkhalter to trace the origin and history of 20th-century playgrounds, defined as "transitional spaces between the familiarity of home and the unfamiliarity of the city.” Among the maquettes and drawings of these kids’ spaces there is an immersive environment by Tezuka Architects and a terrific movie made by the artists Ei Arakawa and Henning Bohl in collaboration with Arakawa's mother and brother and Bohl's 10-year-old daughter. It’s a true family affair, chronicling the group’s three-week road trip touring historical playgrounds through Japan.

Then, if further illustration is needed, a literal playground has been brought to the museum in the form of “Lozziwurm,” a sinuous, red-and-yellow-striped structure of snakily winding tunnels, designed by Yvan Pestalozzi (b. 1937), that has been placed out front of the museum for everyone to use (at least those small enough to fit its child-size apertures).

In the first pages of their catalog, the curators put forward their conviction “that art makes life better." This mantra-like concept infiltrates every aspect of the exhibit, but it may be best translated in the work of Vietnamese artist Dinh Q. Lê (b. 1968), who reunited 100 paintings and drawings by men and women who served on his country’s front lines in the Vietnam War. The installation, which also comprises a film in which the artists speak about their homeland’s history and the power of art, provides the most poignant moment of the exhibition.