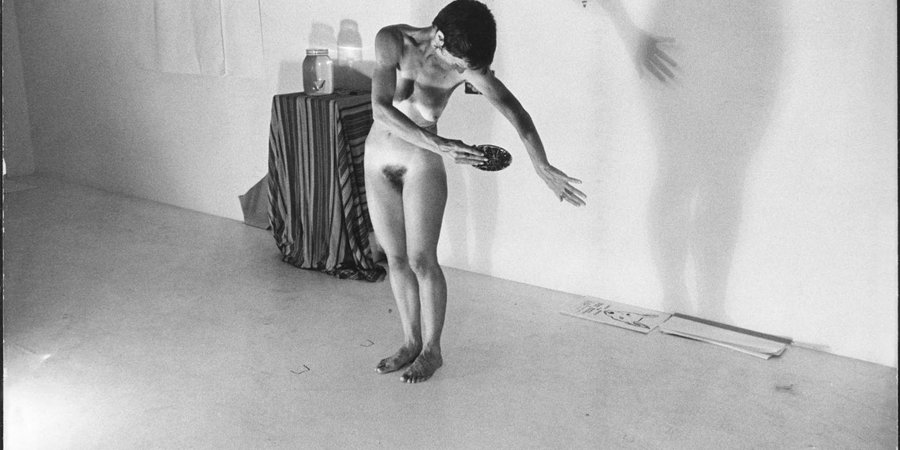

One of the founding figures of video and performance art, Joan Jonas has gone on to test the boundaries of time-based mediums through her visceral, conceptual pieces. She has also been chosen as the United States representative at this year’s Venice Biennale, in honor of her significant contributions to American and international art. Here, the artist describes some formative experiences and shares one of her lesson plans—a “creative exercise program” of sorts, excerpted in its entirety from the new book AKADEMIE X: Lessons in Art + Life.

I lived in New York City until I was twelve. For kindergarten and first grade I attended The Walt Whitman School. This was a ‘progressive’ school. I was asked every morning what I wanted to do. I always wanted to paint. I remember the row of easels with large pads of paper, brushes and a line of jars containing different colours. It was pure pleasure. I didn’t learn how to read or write, so during the summer months my grandmother taught me. Soon, I was sent to a different school that, while being very rigorous academically, had an excellent art programme in which we could learn various crafts including wood working, intaglio, drawing, painting and working in clay. I think that children should figure out how to draw at the same time as they are learning how to read and write.

One advantage to living in New York was visiting the Metropolitan Museum and going to the Egyptian wing. I remember looking at the miniature dioramas of everyday life in the markets of ancient Egypt. I also visited the Museum of Modern Art, returning to see, for example, The Bather by Cézanne, The Dance by Matisse, or The Palace at 4 a.m. by Giacometti. Such inspiring experiences of concentrated looking can suggest ways to translate concepts and ideas into form.

Art school wasn’t on my mind as an undergraduate at Mount Holyoke College, where I studied art history, literature, and sculpture. At that time, I didn’t imagine myself as an artist, yet I worked with clay, fashioning small figures from a live model. I particularly enjoyed making plaster casts. I love the feeling and properties of plaster. My teacher was Henry Rox.

Finishing at Mount Holyoke, I didn’t know what to do with my passion for art history and making things. So, in order to find out, I decided to study at art school. Henry Rox suggested that I go to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston to avoid my family connections in New York. So I followed his advice and went to Boston, where in the second year at the Museum School we worked from a model on large clay figures on armatures. This was difficult because of my lack of knowledge of anatomy, and the results were discouraging. However, the artist Harold Tovish taught me how to begin to draw by slowly, carefully and minutely tracing the contour of the model or the object before us while considering its placement in space on the paper. I didn’t consider myself an artist at that time. I was simply in the process of stumbling forwards. I had no idea how I would become an artist, but I had to find a way, and drawing was a thread that l followed.

Around four years later, I attended the MFA programme at Columbia, where I continued with sculpture. But more inspiring at the time than the studio courses were those in art history and literature, such as an art history course in early Chinese bronzes, a course in Impressionism with Meyer Shapiro (who was a brilliant and charismatic figure), and a class in modernist poetry taught by Fred Dupee. In particular, Shapiro’s lectures were fascinating, in that he would combine a consideration of Impressionist painting, for example, with developments in nineteenth century technology. In the poetry class we read the works of William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound and HD (Hilda Doolittle), among others. (Recently, I based one of my pieces on an epic poem by HD.)

College is only one aspect of life. It is vital to remember that learning can happen anywhere and that it can be intentional or accidental, inside or outside of art school.

In the late 1950 to the mid-1960s, the cost of school was a fraction of what it is now. For me, school was a place where one could explore and find a way of working before venturing out into the world. I had time to blunder, to experiment, to explore processes and materials. I met many interesting people, a few of whom I’m still in touch with, such as the poet Susan Howe, who was studying painting at the Museum School in Boston at the same time I was there. But times have changed dramatically. The cost of attending art school has become prohibitive, and the debt – for many – is very difficult to pay off. It’s a burden that shouldn’t be borne by an artist trying to find his or her voice. There are other ways to acquire knowledge, such as initiatives where younger artists organize their own alternative means of sharing and transferring knowledge. One can educate oneself outside of the institution, especially within communities of artists and intellectuals. It’s important to self-organize, and artists have already formed such communities and initiatives.

After Columbia, I moved downtown. It was the mid-1960s. I found a part-time job as a secretary working for Richard Bellamy at the Green Gallery on 57th street. Working at the Green Gallery was an incredible experience. It was at the centre of a scene in which Bellamy was discovering and showing many of the most interesting artists of that time (Claes Oldenburg, Mark DiSuvero, Yayoi Kusama, Jo Baer, Lee Lozano, Lucas Samaras). The 1960s and 1970s were exciting in New York. Before and after my time at Columbia I learned in the street by going to see ‘happenings’, art shows, performances, dance, music and theatre. I went to Anthology Film Archives several times a week. It was there that I was able to watch early Russian, French, German, Japanese, Indian and American films, many of them silent. I was drawn to the idea of montage, one image after another, in the early films of Dziga Vertov, Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin and Alexander Dovzhenko, in addition to their use of close-ups to build narratives. The structures of poetry and film informed the structure of my later work in performance and video. During this time I found what I wanted to do, and that was performance. Why performance? There are no formulas.

I began teaching full time comparatively late in life, in the early 1990s, in the New Genres department at UCLA, then at the Art Academy in Stuttgart, Germany, and at the same time the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, and most recently at MIT. I’ve enjoyed much of this experience, particularly meeting students, discussing their projects, and watching their work develop. There have also been ongoing friendships, as well as residencies in different cities, in LA, Austin, Texas, Amsterdam, Stuttgart, Berlin, and Como, Italy. Sometimes the workshops I teach are almost as challenging as the performances I make, and I’ve used materials from my workshops in my work. In this way, the students have really contributed to my thinking.

An example of a workshop based on notes and lessons for a class I taught at MIT entitled ‘Action: Archeology of the Deep Sea’ (2010).

Workshop 1

1. We view films by Jean Painlevé: L’Hippocampe (The Seahorse) 1934, Les Danseuses de mer (Sea Ballerinas) 1960, Amours de la pieuvre (The Love Life of an Octopus) 1967, and many others.

2. We consider modern poetry and film as examples of structure – e.g., how to structure a work or a sequence of actions and/or images in relation to a subject, in this case, the deep sea. We begin with our bodies as material – as objects moving in space and time – with awareness of others, developing sequences of image and sound. Students are asked to bring material with which to build an image in time involving the subject of the sea.

Some simple warm-up exercises:

i Walk while allowing the weight of you arms and legs to carry you.

ii Move as if at the bottom of the sea, slowly, as if under great pressure, as through the medium of water or in a sandstorm (walk on sand in the wind).

iii How long does it take you to move from here to there?

iv Find a sequence of gestures.

v Add objects and sound.

3. Set up a video camera mounted on a tripod connected in a closed-circuit loop to a projection on a large screen, framing a space for performance while framing a detail of that space, again involving the participants as performers, and combine a series of actions in relation to objects/props.

4. Make a sound track.

Bring objects that produce sounds.

How does sound change the image?

How does the space alter the sound?

Provide a sound for others.

Make a two-minute performance with sound.

Imagine the shape of a sound, then construct an image.

Work with voice; give a friend a sentence, repeat while walking, listen to your voice.

Walk one by one to the microphone and speak – amplified.

Speak without microphone.

5. Draw for the camera.

Draw with your camera.

Watch yourself draw.

Move into the drawing and draw with your body.

Draw without looking.

Place two ideas side by side.

Make a list: cut, montage, frame, overlay, dissolve.

Be comfortable with a sense of unease.

Draw the space between the shapes.

Inscribe, scribble, sketch, delineate, trace.

Imagine large shapes – move among them while drawing in your notebook.

6. Be aware of others.

Imagine something you don’t want to say.

Move while thinking how to say it.

How does this generate movement?

7. Place a pile of objects in the middle of the room.

Rearrange them and use them in inappropriate ways.

Imagine yourself as someone else.

Be a detective – carry a notebook.

Exchange objects.

Draw daily, design, cook, walk.

Work with masks.

8. Attend magic shows, go to the circus, study fossils, study other cultures (Mexico, for instance).

9. Claim the space and time at a museum. It’s your space. Take advantage of the days when the admission is free. Change your persona. Spend your entire lifetime looking and remembering. Go to the cinema in the afternoon.

Assigned Reading, Viewing and Listening:

Reading:

- Bourgeois, Louise. Destruction of the Father / Reconstruction of the Father, edited by Marie-Laure Bernadac and Hans-Ulrich Obrist. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1998.

Louise Bourgeois was a great visual artist, but also a talented writer. Writing is integral to her artistic practice. She’s very aware of the psychological roots of her work, such as repression and trauma, and she grapples with these themes in her writings.

- Brand, Bettina, Laurent Busine and Inge Jad. La Beauté Insensée: Collection Prinzhorn, Université de Heidelberg, 1890–1920. Charleroi, Belgium: Palais des Beaux-Arts, 1995.

This catalogue from the Prinzhorn Collection at the University of Heidelberg is a record of work by psychiatric patients collected by Hans Prinzhorn. I’ve always been interested in work produced outside of the system, and this invaluable archive and record has been endlessly inspiring for myself and other artists.

- Forti, Simone. Handbook in Motion. Halifax, Canada: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1974.

Simone Forti is one of the most innovative dancers from the 1960s to the present, incorporating humour and animal movements into her choreography. In this book, she intuitively translates the improvisatory nature of her dancing to her writing.

- Galeano, Eduardo. Memoria del Fuego 3. El Siglo del Viento. Madrid: Siglo XXI, 1986. Translated by Cedric Belfrage as Century of the Wind: Memory of Fire Trilogy, Volume 3. London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1988.

The third book in his series Memory of Fire, Eduardo Galeano’s Century of the Wind is a poetic history of Latin America. His texts, based on real events and historical figures, are written in the form of short narrative entries. One can find many provocative, hidden stories in these volumes.

- Keene, Donald. No and Bunraku. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

In this book, Donald Keene, one of the foremost authorities on Japanese art, investigates No and Bunraku theatre, forms that have influenced many artists from Antonin Artaud to William Butler Yeats. These two forms are musical, visual and relate to dream and fantasy. With its ingenious use of props, objects and staging, Japanese theatre is yet another source for visual artists working in the area between painting, sculpture and performance.

- Reynolds, Ann. Robert Smithson: Learning from New Jersey and Elsewhere. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

This is one of the few important books about Robert Smithson’s practices and concerns. Reynolds’s readings of ephemera in the archive pushes her study beyond her subject to broader art-historical and archival concerns.

- Rudofsky, Bernard. Architecture Without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1964.

It’s always important to look outside of conventional architectural history. In this case, Bernard Rudofsky offers a historical investigation into indigenous architecture, illustrated with fantastic photographs. These examples of communal architecture grew out of the needs, materials and landscapes specific to each individual group of people.

- Serra, Richard. Richard Serra: Writings Interviews. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994.

It’s very important for students to read writings by artists on their own work. One of the most significant sculptors of his time, Richard Serra reveals his preoccupation with bodies, sculptures and space in his writings and interviews. This book elucidates his way of thinking and his serious involvement in contemporary art.

- Sontag, Susan. ‘Happenings: An Art of Radical Juxtapositions’ in Against Interpretation and Other Essays. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966.

Susan Sontag’s book Against Interpretation and Other Essays is complex, but concise. I assign my students her essay ‘Happenings: An Art of Radical Juxtapositions’ because it’s the best description of Happenings I’ve ever read and it captures the motivation and ideas behind the whole movement.

- Tuchman, Maurice and Judi Freeman. The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1989.

This was a really beautiful show that included works by relatively unknown artists at the time (1986) such as Hilma af Klint, artists experimenting with images in various media such as Jordan Belson and Harry Smith, and well-known contemporary artists such as Matt Mullican and Dorothea Rockburne. The catalogue is also an excellent reference book for the various philosophical and occult movements in Europe and North America, ranging from alchemy, Kabbalah and the fourth dimension, to Russian occult literature.

- Warburg, Aby. Bilder aus dem Gebiet der Pueblo Indianer in Nordameriker. Berlin: Wagenbach, 1988. Translated by Michael P. Steinberg as Images from the Region of the Pueblo Indians of North America. New York: Cornell University Press, 1995.

This is a very important book concerning the German art historian Warburg’s visit to the American Southwest at the end of the nineteenth century. The book includes the lecture he delivered almost thirty years later to doctors at a Swiss hospital where he was recovering from a nervous breakdown. It’s a deeply moving look at how Europeans viewed the culture of the Native Americans, which, we now know, was threatened by their presence in America. Though Warburg’s readings of the Native Americans’ culture are problematic, he was one of the first to consider art history from a cross-cultural view.

- Warner, Marina. Stranger Magic: Charmed States & the Arabian Nights. London: Chatto & Windus, 2011.

This is just one of Warner’s important books, many of which deal with the issues of magic and feminism in myth and history. This book, involving the Arabian Nights, is a particularly timely study of this great work of literature. Importantly, Warner finds parallels between magical thinking in the past and the present.

Viewing:

- Deren, Maya, dir. Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. Microcinema International, 1985. Film.

Deren’s Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti is a compelling account and recording of voodoo ceremonies in Haiti rarely captured on film. The film documents important rituals that incorporate drawing, sacrifices, obsessional dances and possession.

- Marker, Chris, dir. Sans Soleil. Argos Films, 1983. Film.

Sans Soleil, one of Marker’s essay-films, presents images from his travels, mostly in Japan and Guinea Bissau. A profound look at memory and global histories, Sans Soleil is a truly innovative take on the essay-film.

- Ozu, Yasujirō, dir. Tōkyō Monogatari (Tokyo Story). The Criterion Collection, 1953. Film.

Tokyo Story is one of the many important films by Ozu, who, along with Kenji Mizoguchi, is among the greatest Japanese film-makers from the early-to-mid-twentieth century. His use of camera and movement in relation to architecture creates a completely unique sense of space. One can also learn a great deal about Japan in this period, when it was going through profound cultural and political changes.

- Vigo, Jean, dir. L’Atalante. Gaumont Film Company, 1934. Film.

Vigo was an early French filmmaker who also directed Zéro de conduite, an important influence for the French New Wave. L’Atalante is poetic and mysterious, playing in the margins of magical realism.

Listening:

Three of the most important composers of contemporary music are La Monte Young, Pauline Oliveros and Morton Feldman. Young’s work is significant in its sense of duration and time, particularly in relation to the experience perceived by the body in the presence of live music. Oliveros experiments with both traditional and electronic sounds to explore meditation, myth and ritual. Feldman’s avant-garde experiments with graphic musical notation blurred the boundaries between sound, music and the plastic arts.