Forget about you, dear reader, how will I manage not to bore myself to tears with this? Art Basel feels like round 87 in a long, drawn-out boxing match and I shudder to think that I have to put fingers to the keyboard so quickly after the last art-fair recap, so let me disclaim myself from the onset. What more could I possibly say that hasn't already been said?

Art fairs seem to mirror the plot of the film Groundhog Day, repeating (and repeating) themselves, with many of the same people buying much of the same art in generic settings indistinguishable from one to the next. Rafael Nadal was depicted on the front page of the Times in an all-encompassing scream of ecstasy and I began the week wondering if I'd encounter anything in the aisles of the fair that would inspire such raw emotion. Probably not, but there were a few notable sightings and surprises. Read about them here, in this diary of the fair.

Day 1: Saturday, June 8

But, before I get to the main Basel event, I spent a weekend filled with openings at galleries, museums, and collector’s homes in Zurich. My first stop was an early Jean-Michel Basquiat painting exhibition at Bruno Bischofberger. With the artist's radioactive market causing much foaming at the mouth these days, there is sure to be a Basquiat show coming to a city near you sometime soon. Thanks to the recent Sotheby’s S2 selling exhibition and Gagosian’s blockbuster show, the Basquiat brand is like Starbucks art now, albeit at $50 million a cup.

The impressive refurb of the Löwenbräu building, which houses the Kunsthalle and Migros museums, exceeds much of the art that’s on view. A gallery trend I noticed in Zurich was big spaces filled with little art, much of which wasn't very good. Like Wilhelm Sasnal’s new paintings at the Hauser & Wirth franchise—underwhelming across the board, even though some featured vehicles and race-car drivers, which I am typically a sucker for.

At Eva Presenhuber, Ugo Rondinone had a show of crudely formed rock figures that could have been the children of his Rockefeller Center installation. Fifty-seven children, to be exact, with names like “the calm,” “the ardent,” “the jovial,” and “the provocative,” and they all managed to be cute, in a rough-hewn sort of way.

That first night, I was meant to visit a KAWS installation outside if the city in a disused factory. After 45 minutes in the car, I realized the drive was going to last considerably longer, and so did a U-turn back to town. After that misstep, I hit a collector’s house, where the footprint of the all-knowing, heavy-handed advisor was firmly present, with boxes ticked for each of today’s market darlings. At least I ended the night back in the gallery district where I got to see some good works, like the wee Elad Lassry photos at Francesca Pia gallery, which are delectable confections.

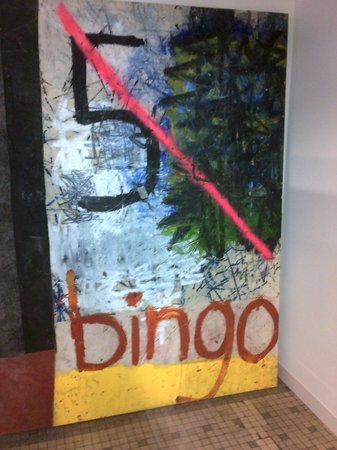

Oscar Murillo at Liste.

Oscar Murillo at Liste.

Day 2: Sunday, June 9

Another day of Zurich galleries, a luncheon, and more blah, blah, blah. After a while, I lost any sense of criticality and couldn’t judge what was good or not. Sometimes I feel more drawn to the windows and the view out.

I attended an annual dinner on the luscious grounds of a beautiful house overlooking the lake—a residence that was stuffed with more art from the same consultant as last night, give or take pieces from a few other helpful hands. It was not a bad setting to take it all in, until a woman introduced herself and, confusing me for Hans Ulrich Obrist, described what a privilege it was to meet me.

I am amused by the concept of the omnipresent Obrist, and a fan, but the scenario was a little weird as I had only just blogged about him for Monopol magazine that morning, adding a twist to the whole art-world Groundhog Day scenario. I didn’t quite manage to tell Obrist about it when I saw him at the neighboring table though.

On the shared bus back to the city after dinner, which is about the closest the art world comes to sharing a sense of community, one dealer tried to sell me an artwork. I asked about the prominence of the central image, and if the composition was pronounced and strong or faded and faint, to which he replied that the composition was “mysterious.” Coming from anyone else, the connotation wouldn’t be as dubious, but it was from this particular gallerist.

It’s amazing the kind of fear and dread that a powerful art-world figure can instill even in the macho, tall, and brawny. I saw a friend of mine reduced to a subservient child in the presence of a founding member of what I call the Zurich mafia. (Admittedly, she scares the wits out of me too.) But the Swiss don't always seem to be so susceptible. On the bus, the Rubell family occupied the first few rows of seats and, despite the great protestations of Mera, the matriarch, the driver insisted on following his own route and dropped them off last.

I love the intrepid Rubells, even though we’d never do business together in a million years. I've known them for decades and they put me through an inquisition back in the day and still didn't buy anything. But hats off: if she and Charles Saatchi had a baby; it would be world's first art superhero—100 studio visits before it could walk.

On my way back to the hotel room for the night, another dealer got off on the same floor and proposed an i-deal to me on her device in the hallway. When the elevator opened to a contemporary art-hating industrialist that I know, it felt more illicit than getting caught in a heated embrace.

The new Herzog & de Meuron-designed building at Art Basel.

The new Herzog & de Meuron-designed building at Art Basel.

Day 3: Monday, June 10

Off to Basel, where the hotels are known for a kind of highway robbery during high-profile events, charging guests rates so disproportionate to their value as to be extortionate. The rooms are so small you must walk sideways around the bed and keep the bathroom door open to capture an extra sliver of light.

One learns to economize with the little space. So the bathroom morphs into an impromptu junior suite and I end up working on the toilet, chasing anything resembling natural light. I subsist on minibar Pringles, which get me every time, even though their ingredients read like a chemistry experiment.

I headed out for the opening of the design fair, Liste (the emerging-art fair), and the Art Basel Statements and Unlimited projects, wondering who I might meet on the train and if I should troll the aisles collector collecting. Would I encounter a situation like last year, when a super high-profile London dealer tried to use his VIP pass to get a reduced rate on the train fare? It’s strange to attend an Art Basel fair actually in Basel.

The Liste building is located in an old brewery (why is art attracted to these old booze-soaked halls?) made up of fractured architectural nooks and crannies that resembles a rabbit warren. It piques my Woody Allen-esque neurosis and fear of getting lost—which definitely happened.

With so much emerging art on offer, it’s harder to rely on easy name recognition, and one has to instead look at art for art's sake, rather than playing name that tune. It turns out that there is a lot of cheap young art today that looks exactly like a lot of expensive young art today. The paintings of Liam Everett are dead ringers for Tauba Auerbach, and the disembodied hoodies by Keith Farquhar? Call them the poor man’s David Hammonds.

Admittedly, even someone like me who needs a GPS to get to the newsstand, one falls into a rhythm looking at art in a fair context—a thrilling meander. An artist I like is David Ostrowsky who shows with Javier Peres, and whose minimal, though sloppy, flourishes seem so haphazard, quick, and effortless. Yet there are never any works available. I asked the director why the artist couldn’t bang out a few more canvases, as they certainly couldn’t take long to make. He replied that he just got back from the studio, where he had tried to do just that, but to no avail. I never liked artists all that much.

The new Herzog & de Meuron building at the main fair is elegant and ginormous. Upon entering the vast site, I was faced with millions of people I didn’t recognize, which struck me as a healthy sign of the market. More than one work required waiting in a lengthy line, while other installations have been made even bigger. Theoretically, these are meant to be non-commercial in nature, but as one player in the trenches succinctly put it: “Everybody here just wants to make money.” There you have the ethos writ (extra) large.

A few works by He An and Alfredo Jaar employed bright, Blitzkrieg lighting, rendering spectators all but blind—a good, neighborly strategy to ensure that viewers only have eyes for you.

When it comes to videos, my attention span is like a mosquito. I don’t think I have ever watched an art film from start to finish, never. Nor do I foresee doing so.

As for the design fair, in which I used actively participate, it doesn’t seem to matter how good it looks in its new setting (and it does): I can't escape the feeling that I'm at a more expensive version of Bloomingdale’s.

We are all so busy tapping away our lives on our phones that we sometimes forget to actually live them. So I will have to remind myself to look a little more closely tomorrow, especially now that I’ve turned in this article, “Sent from my BlackBerry® wireless device.” I am frequently told that I always have a smile on my face, which, despite the occasional darkness belying it, is actually true. I love art, and even a few of the people involved.

Resembling a planet orbiting around a star, Meschac Gaba's Citoyen du Monde: balloon (2013) partly eclipses one of the exhibition center's industrial lights.

Resembling a planet orbiting around a star, Meschac Gaba's Citoyen du Monde: balloon (2013) partly eclipses one of the exhibition center's industrial lights.

RelatedLinks:

Kenny Schachter's Art Basel Diary, Part 2