If taking the pulse of the contemporary art world is your idea of a good time, browsing the booths at this year's NADA New York is an ideal place to start. After all, the artists that exhibitors bring to the fair tend towards the young and experimental (as do the galleriests themselves), and the fair can function as a kind of barometer of what’s capturing the imagination of the art world's current up-and-comers. Here are three mini-trends that jumped out to us in our tour of Basketball City this weekend.

UPCYCLING

Many contemporary artists have grown up with some form of the credo “reduce, reuse, recycle” imparted to them at a young age—and, if NADA New York is anything to go by, they’ve clearly taken the second term to heart. Repurposed materials are everywhere, and the works below are just a taste of the ways in which found objects are being employed in the fair.

One prime example is Samuel Levi Jones, who makes wall works (shown here at Patron Gallery) out of discarded encyclopedias and text books. After soaking the volumes to more easily separate the covers from the pages, the Indiana-born artist simply arranges them into grids by subject, as in the piece Dirty Water shown above, which is made solely from law books.

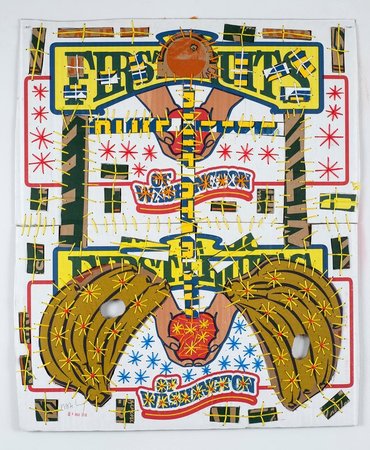

Ed. Varie’s booth is given entirely over to works by Mark Delong, a self-taught artist who has recently turned to embroidered cardboard as his medium of choice. He finds material on the streets near his home in Vancouver’s Chinatown and stitches them together into colorful compositions he refers to as “tapestries,” often granting them ridiculous titles like Bigger Bananas are better than Little ones and were not talking about financial growth, shown here.

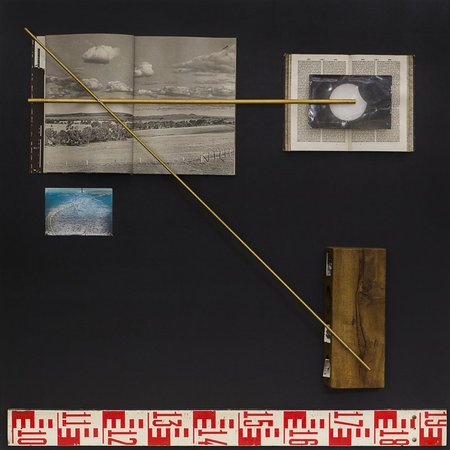

The Peruvian sculptor Fernando Otero collects objects, photographs, books, and more from flea markets and beaches to fill his wood-framed boxes of ephemera shown by LAMB Arts. Otero compares his process of preparing these pieces to police investigations, pulling seemingly disparate items together to form a version of the truth. (Some may also descry the influence of one Joseph Cornell.) When visiting LAMB’s booth, don’t forget to take a step back and appreciate the large installation on the back wall, which takes you inside one of his compositions.

VIDEO GAMES

Far from a mindless diversion for the kiddies, video games in 2016 are a multibillion dollar industry as well as one of the most fertile sites for radical experimentation in storytelling and animation. It should come as no surprise, then, that games are well-represented at a youthful fair like NADA. What’s more, many artists are going beyound the screen to bring these virtual realms into our physical world.

The Cologne gallery Schmidt & Handrup have given over their entire booth to works by the German artist Timo Seber, who is clearly grappling with not only the aesthetics but the social and economic implications of video games. Two series are on view in the booth: leather t-shirts printed with screenshots of the massively popular online game DOTA 2, and glass panes bearing information about microtransactions in games (small in-game purchases for new gear or content that are major money-makers for “free to play” games) and gym-class climbing ropes, a reference to another, more physical form of fun.

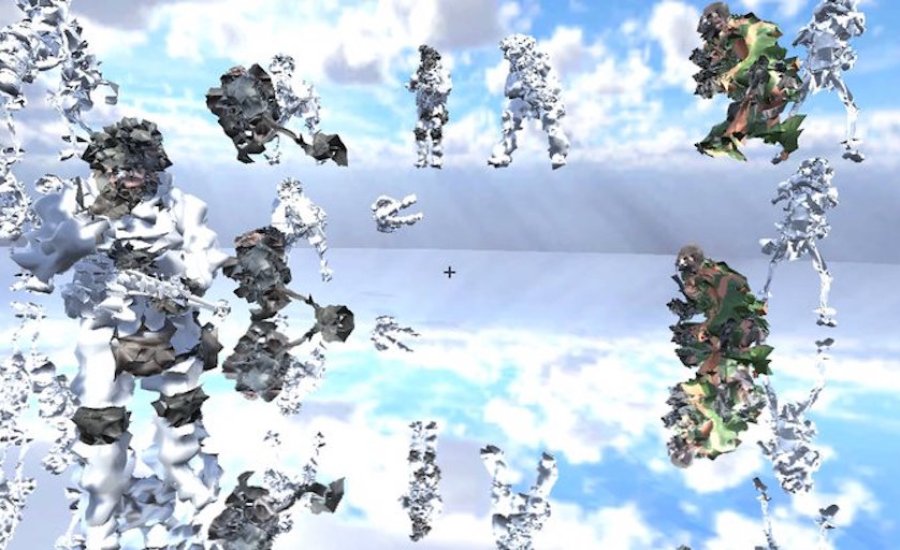

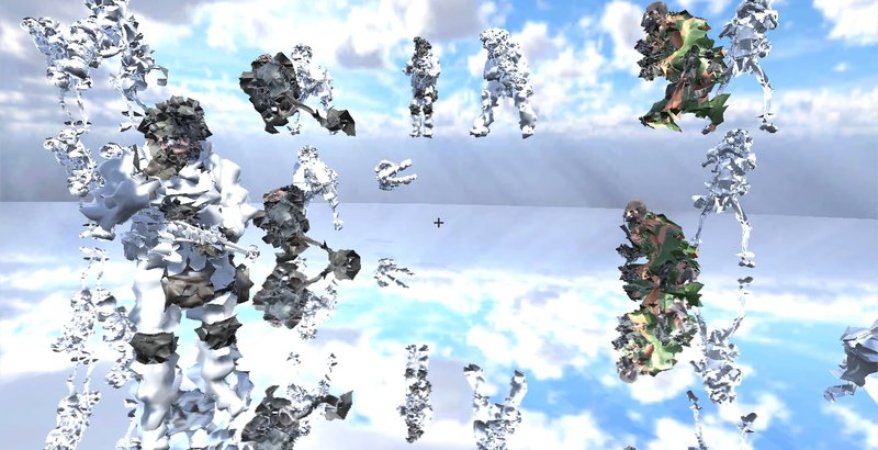

Rachel Rossin is one of only a handful of artists making a concentrated effort to explore the possibilities of virtual reality as a site for art making, and her offering at NADA is a prime example of what the medium can do. Her piece SOURCE: CLAUDE GLASS in SIGNAL gallery’s booth lifts characters from her favorite video games (including Call of Duty and Life Is Strange), chosen for the preprogramed animation loops that still manage to evoke memories of the games years after they’ve been played. Don’t miss the floor of the booth, either, which is made up of marble tiles laser-etched with stills from Rossin’s work.

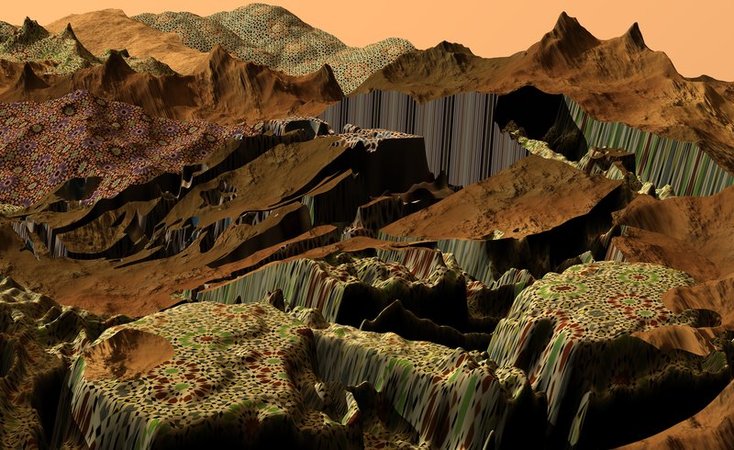

While her works are not directly pulled from video games, Yael Kanarek’s digital landscape prints in bitforms gallery’s booth are clearly partake in the aesthetics, albeit with a different departure point than most of her younger counterparts. The works on view at the fair were made in 2002, long before the current glut of Post-Internet and digital-native artists starting coming to the fore of contemporary art. Equally prescient are her line drawings on the prints, which map the visitors to her net art work World of Awe in a clear prefiguration of the user-tracking techniques companies like Google and Facebook are employing to shape our lives today.

URINALS

Yep. They’ve been a running joke (or fruitful reference, depending on your disposition) in the art world since Marcel Duchamp (or was it Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven?) scrawled “R. Mutt” on a males-only toilet and sent it off to the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibition in New York. Some 99 years later, urinals are making a strong showing at NADA New York, with no fewer than three examples on view at the fair.

The most direct Duchamp reference comes from the Russian-American artist Alexander Kosolapov, who has been making his Pop-inflected works since he emigrated to New York from the U.S.S.R. in 1975. His piece Russian Revolutionary Porcelain in Galerie Sébastien Bertrand’s booth is the classic urinal with a Malevich-esque red-and-black square painted in the center in a more or less straightforward layering of art-historical references.

The young Israeli artist Oren Pinhassi takes the floor-level standing urinal as his subject in a slight departure from the classic wall-mounted unit. He’s created a group of glass-backed sculptures for Tempo Rubato’s booth that his dealers describe as at once “voyeuristic” and “sensual”—not unlike the experience of using a public restroom.

Although her work isn’t quite a urinal—“bedpan” is more accurate—Jamie Sneider nevertheless gets in on the toilet wavelength at NADA, albeit with a far more personal (and certainly less light-hearted) point of departure. Her works in the Turin gallery Neochrome’s booth all revolve around her experience of watching her mother lie sick in a hospital with a serious illness, a painful memory that lends a somber note to the fair. The aforementioned bedpan goes right in step with the bleached and dyed fabric works on the wall, each evoking an empty hospital bed.