The annual Art Show of the Art Dealers Association of America is where careers are re-made. Although the fair has skewed more contemporary in recent years, it’s still the go-to March fair for dealers looking to show off a prized estate or elevate the reputation of a veteran artist. That tendency appears to be even more pronounced at this year’s ADAA, as a larger scholarly and market-driven movement to identify undersung greats of 20th-century art prompts dealers to give the usual blue-chip suspects a rest. Below, Artspace previews some of the (re)discoveries.

BARRY LE VA

David Nolan Gallery

Barry Le Va, Working installation at the artist's studio, Los Angeles, 1967. Courtesy of the artist and David Nolan Gallery, New York

Barry Le Va, Working installation at the artist's studio, Los Angeles, 1967. Courtesy of the artist and David Nolan Gallery, New York

Whether or not they know it, the many young artists today who make haphazard-looking, improvisational installations owe something to Barry Le Va. A pioneer of the diffuse style known, variously, as “Scatter Art” and “Process Art,” Le Va has dispersed materials such as felt, chalk, flour, and shattered glass across large expanses of floor in a way that looks impulsive but is actually somewhat scripted. (His pieces generally begin with written directives and diagrams.) Le Va has long been admired by critics and art historians (he was included in MoMA’s seminal 1970 group show “Information,” and the ICA Philadelphia gave him a retrospective in 2005), but he’s still not nearly as well-known as his contemporaries Donald Judd and Richard Serra. David Nolan’s ADAA booth, which reprises Le Va’s late-1960s “distributions” of felt, aluminum, and steel in a single installation, should help to raise his profile.

Carolee Schneemann, Meat Joy, 1964. Silver print, 23 3/4 x 20 1/4 in. Photo: Al Giese. Courtesy of C. Schneemann and P.P.O.W., New York

Carolee Schneemann, Meat Joy, 1964. Silver print, 23 3/4 x 20 1/4 in. Photo: Al Giese. Courtesy of C. Schneemann and P.P.O.W., New York

As many a liberal-arts undergrad can tell you, Carolee Schneemann made Feminist and Performance Art history in the 1970s with her piece Interior Scroll (in which she stood naked on a table and pulled a long strip of paper out of her vagina, becoming, in her words, “both image and image-maker.”) Through the efforts of the two galleries that have recently teamed up to represent her, P.P.O.W. and Galerie Lelong, the rest of Schneeman’s visceral and confrontational oeuvre is now getting more attention. At the ADAA, P.P.O.W. is showing vintage photographs from performances including Meat Joy (1964), a messy experiment in group painting in which barely clothed performers writhed in heaps of raw fish, chickens, and sausages; Schneeman has described it as an “erotic rite.”

MCARTHUR BINION

Galerie Lelong

McArthur Binion, Circuit Landscape: No. 5, 1972. Oil stick and dixon wax crayon on aluminum, 25 x 32 in. Copyright of the artist. Courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York and Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago. Photo: Joseph Rynkiewicz

McArthur Binion, Circuit Landscape: No. 5, 1972. Oil stick and dixon wax crayon on aluminum, 25 x 32 in. Copyright of the artist. Courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York and Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago. Photo: Joseph Rynkiewicz

The Chicago-based African American artist McArthur Binion was long hidden in plain sight, as a maker of quiet Minimalist grid paintings à la Sol LeWitt during a period (the ‘80s and ‘90s) in which brash Expressionism and strident identity politics dominated the medium. But that narrow view of late-20th-century painting has been widening in recent years, and when the Chicago gallery Kavi Gupta exhibited Binion’s early work in 2013 the art world was more than receptive. The septagenarian’s breakout moment continued this past fall at Lelong in Chelsea, where he showed new, subtly biographical grids made by layering paint stick over passport photos and copies of his birth certificate. At the Art Show, those who missed the Kavi Gupta exhibition can catch up on Binion’s paintings on aluminum and canvas from the ‘70s.

BEAUFORD DELANEY

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

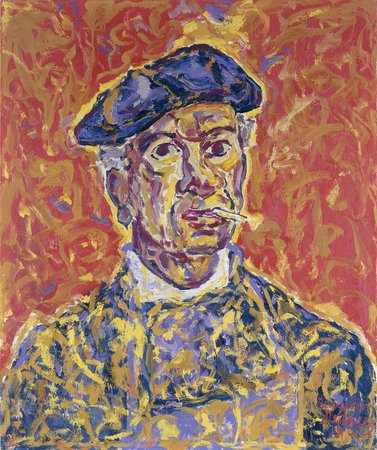

Beauford Delaney (1901-1979), Self Portrait, 1962. Oil on canvas, 25 1/2 x 21 1/4 x 3/4 in., signed and dated. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

Beauford Delaney (1901-1979), Self Portrait, 1962. Oil on canvas, 25 1/2 x 21 1/4 x 3/4 in., signed and dated. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

As the art world slowly starts to recognize the contributions of African American artists to the history of abstraction, one of the figures it must contend with is Beauford Delaney (1901-1979). Delaney contributed colorful figurative scenes and portraits (of his friend James Baldwin, among others) to the Harlem Renaissance before becoming a full-on Abstract Expressionist in mid-20th-century Paris. Rosenfeld’s booth will host a mini-survey with works from all phases of Delaney’s career—including some of the exuberant abstract canvases, with small, feathery gestures in bold hues of red and yellow, that curators are now coveting.

HEDDA STERNE

Van Doren Waxter / 11R

Hedda Sterne, N.Y. # 7, c. 1955. Oil on canvas, 39 x 39. 1/2 in. (99.1 x 100.3 cm). HS 113 © The Hedda Sterne Foundation, Inc. / Licensed by ARS, New York, NY

Hedda Sterne, N.Y. # 7, c. 1955. Oil on canvas, 39 x 39. 1/2 in. (99.1 x 100.3 cm). HS 113 © The Hedda Sterne Foundation, Inc. / Licensed by ARS, New York, NY

Visitors to the inaugural exhibition of the downtown Whitney couldn’t help but notice Hedda Sterne’s painting New York, New York 1955 in the Abstract Expressionism gallery, stealing the show from Pollock and de Kooning with its assertive evocations of urban architecture. At the combined ADAA booth of Van Doren Waxter and 11R, Sterne will be shown in a more contemporary context; works from her series of spray-painted abstractions will be exhibited alongside new paintings on Plexiglas by Mika Tajima, who uses a similar technique to very different effect.

Jules Olitski, Moon Momma, 1992. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery, licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Jules Olitski, Moon Momma, 1992. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery, licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Jules Olitski got his start as a Color Field painter and is still associated with that movement, but he outlived it by decades (he died in 2007) and carried its spirit of technological innovation forward into new bodies of work. In the 1970s, he moved from stain painting into misty-looking allover abstractions made with industrial spray guns; later, in the ‘80s and ‘90s, he used household painter’s mitts to push gobs of thick, iridescent acrylic gel around the picture plane. Works from no less than seven different series will be on view in Kasmin’s mini-survey of Olitski at the Art Show, which spans 45 years and begins with works from the artist’s first exhibition in New York (at Alexander Iolas in 1958).