The annual Seven on Seven conference starts with a straightforward idea: pair off seven of-the-moment artists with equally cutting-edge technologists and challenge them "to make something new together" over the course of 24 hours. This year’s edition, run by avant-garde net art organization Rhizome and hosted by the New Museum this past Saturday, May 14th, did away with the single-day rule to allow the pairs more flexibility, although the conference retained its casual, ad hoc vibe—most of the speakers noted at some point that they only finished their presentations that morning. Even Rhizome’s artistic director-cum-MC Michael Connor seemed charmingly unprepared at times, perhaps a fitting state for an event made up of dreamers from both sides of the right-brain/left-brain divide.

The collaborations ranged from consumer prototypes and fanciful business proposals to speech-bot plays and infinite hotels (more on all these in a moment). Overall, however, the projects tended toward common themes of emotional connection and personal engagement—as opposed to "social" engagement—across, through, and beyond technologies. The conference is forward-thinking, of course, but the participants seemed mainly preoccupied with looking for ways to reclaim a kind of affective reality that technology may be eroding.

Furthermore, these projects were not just answers to the complaints we hear so often about digital culture's plentude of empty distractions and mindless, here's-what-I-had-for-lunch overshares; rather, they showed their creators striving for new, meaningful collective connections using the technological structures we’ve all come to depend on.

What follows are seven key ideas from the conference. They just might prefigure some changes to come.

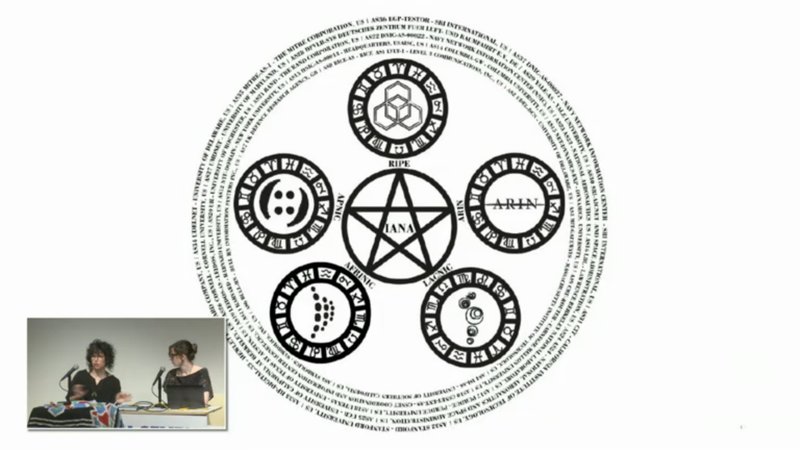

Myths and Legends for the Internet Age

Pop quiz: what version of the Internet Protocol does this website use, and why is it important that it’s updated? If you answered “What on earth are you talking about?” you’re in good company. For the vast majority of Internet users (this author very much included), the technicalities of the websites, devices, and algorithms that structure our lives remain opaque, swathed in a layer of technical jargon unintelligible to all but the initiated. It’s precisely this gulf between universal use and popular understanding that Meredith Whittaker (founder of Google’s Open Source Research and Security Group) and the artist Ingrid Burrignton attempted to bridge. How? By using the time-tested and pleasantly low-tech method of fantasy storytelling.

Framing their tale as deriving from a grimoire (a medieval book of magic), they describe the legend of the shifting IP addresses. In short, the IP4 system most websites currently use only allows for some 4.3 billion addresses, while IP6 makes room for some 3.4×1038, a quantum leap of sorts that is creating all manner of backend issues. It’s a dry topic with limited appeal, but by framing the story in terms of warring fiefdoms (with strange names like “Comcast” and “Verizon”) battling over control over “rough telepathy” (which sounds a lot like the World Wide Web) that is accessed through “scrying mirrors” (computer screens), the tale takes on a kind of gripping dramatic heft more often associated with HBO miniseries than technical manuals.

It’s an example of the Seven on Seven panelists attempting to bring high tech into more familiar realms, positioning the history of Internet infrastructure as one of governments, companies, policies, and altogether human contingencies.

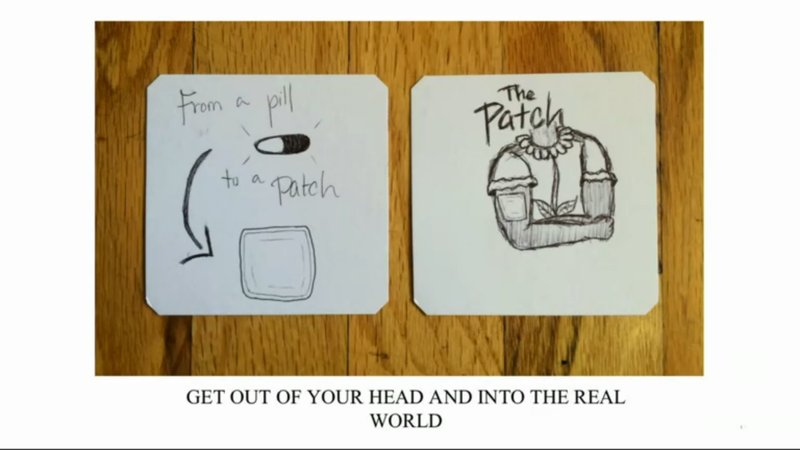

Turn Off, Tune Out, Drop Instagram

Given the background of the conference's second pairing—the New York Times Magazine technology writer Jenna Wortham and net-born rap sensation Junglepussy—their offering at Seven on Seven may come as something of a head-scratcher. It revolved around a hypothetical, Matrix-like device called “the Patch,” a piece of wearable tech that promises to be “an antidote to the illusory demands of modern life,” with those demands being the highly specific ones of needing to needing to conform in person to one's high-profile online persona.

The way it works is that the patch essentially acts as a brain wipe to get rid of all that context—the relationship statuses, the article postings, the job-change announcements, etc.—that prevents peopel from having authentic, un-preconditioned interations when they meet people IRL. If you've ever Googled someone before meeting them in person and then felt weird about knowing their intense relationship saga from "Modern Love," or what their beach bodies look like, you'll understand something of the impetus.

It's a problem that’s especially acute for semi-public figures like Wortham and Junglepussy, but their project points to some of the larger issues being aired at the conference, namely a longing for a more unalloyed connection with others. Interestingly, they’re not proposing jettisoning social media entirely, but rather using their patch as a temporary relief from its near-telepathic insights, so that “people don’t know anything about you besides how you present yourself that day.”

How to implement this more unmediated lifestyle before something like the Patch hits the market? Junglepussy has some straightforward advice: “don’t Google” and “pretend like it's not 2016.”

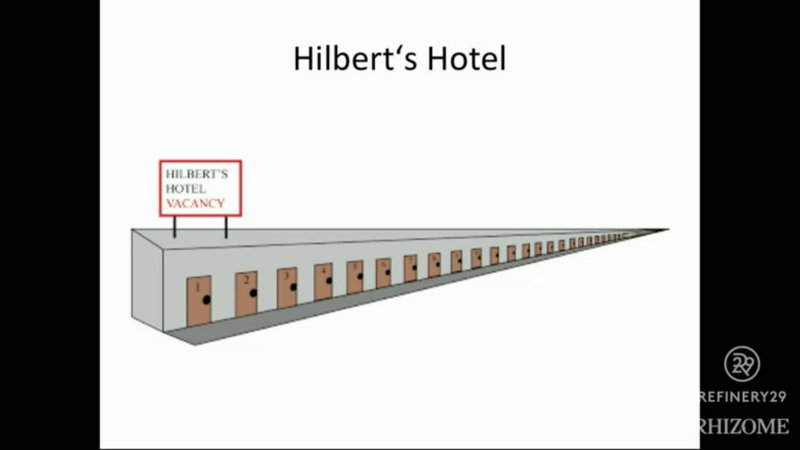

Donald Trump and the Hotel of Infinite Detainment

When the German artist, filmmaker, theorist, and all-around badass Hito Steyerl teams up with someone like Grant Olney Passmore, a mathematician and computer scientist who moonlights as a folk musician, you know things are going to get interesting. Steyerl, as you may know, has a knack for extrapolating wild and fascinating conclusions from the seemingly hard facts of neoliberal capitalism (see here for a few recent examples). Passmore, meanwhile, has worked as the head programmer for the ‘90s net art “supergroup” ACiD Productions and delves into the economic formulas that inform political and financial policies.

Their brainchild? In the form of a letter to everyone’s favorite presidential hopeful Donald Trump, the pair explored the real-life formula used by the U.S. government to determine the attractiveness of illegal immigration by modeling the perceived psychological toll of deterrence techniques like detainment.

Such measurements, which Passmore refers to as “insane mathematics in public policy,” quickly devolve into absurdities—it’s theoretically possible to continually increase deterrence by keeping more and more people in confinement according to this formula, despite the practical difficulties that things like housing, food, and political backlash would entail. Steyerl and Passmore’s solution is for Trump to build a kind of detainment hotel (rather than a wall) with infinite rooms to house illegal immigrants, a mathematically sound but physically impossible endeavor that is nevertheless “provably infinitely profitable” if you charge both taxpayers and detainees (through commisaries) for food, clothing, and other services.

As Steyrl said, “you can prove whatever you want using this mathematics.” She goes on to suggest that these same ormulas for deterrence can be altered to instead favor hospitality, although the economic attractiveness of this alternative plan (to Trump) remained unclear.

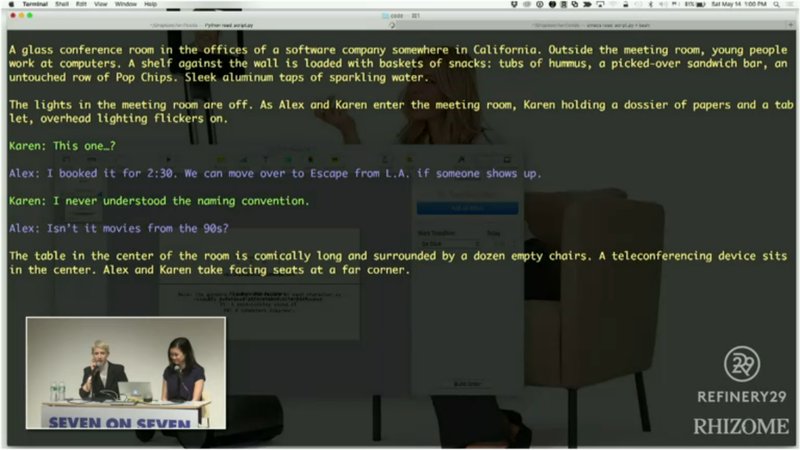

A.I. at the Workplace Water Cooler

Claire L. Evans and Tracy Chou’s offering for Seven on Seven was a play of sorts, one of several explicitly theatrical projects shown at the conference. As might be expected from the evocatively titled "Futures Editor" of Vice's Motherboard site (Evans) and a Pinterest software engineer (Chou) who have made names for themselves in part through their championing of women in technology, their project is more than just a screenplay.

They came up with a kind of robo-performance, with the Mac text-to-speech voices reading off lines written by the pair and the genders of the “performers” randomly selected thanks to some code developed by Chou. The ostensible goal was to challenge audience expectations about gendered roles and speech, particularly in the near-future workplace described in the play. The real interest, however, lay in the content of the piece itself, which revolved around the difficulties an artificially intelligent yet apparently self-aware coworker could have.

There are some funny references to Siri ruining the millennial generation's manners (“Not a lot of please and thank you”) and jokes about dogs not being able to smell A.I., as well as some slightly more serious ruminations on what terms like “abuse of power” might mean when one’s underling has been quite literally built to serve (and knows it). It’s more or less standard sci-fi fare: the machine achieves intelligence beyond its human handlers’ control even as it suggests a certain emotional capacity expressed through quips about “unnecessary” human actions like lunching with friends. But the concept of bantering with your robot work buddy is evocative despite its increasing banality.

Get Ready for Emotional Ergonomics

Emotion figured into several presentations at this year’s conference, but Rana el Kaliouby and Jennifer Steinkamp took it to the next level with their project. It makes sense. El Kaliouby is the cofounder of Affectiva, an “emotion measurement technology company” that’s looking to infuse our everyday devices with mood-sensivite face-reading software—a development she says will soon become as ubiquitous and second-nature as GPS. Her collaboration with Steinkamp, an installation artist who often incorporates digital animation into her work, proceeded logically from both women’s interests. It was one of the more impressive offerings at the event.

What they created was a kind of digital mirror using Affectiva’s software and Steinkamp’s artistic flourishes: looking into their Microsoft Surface tablet created an animated avatar of your visage programmed to study your expressions and recreate them in an exaggerated fashion. A smile creates a flower cascade, for instance, while any hint of anger causes the avatar to nearly explode in rage. This naturally allows for some fascinating feedback loops, where a stray grin by the user sets off the program, which results in another reaction from the user, which in turn drives yet another outpouring of emotion from the tablet.

El Kaliouby’s aim with Affectiva was to give our tech an emotional intelligence to match its cognitive capabilities, but these moments of comical escalation may be even more revealing about the future of “feeling” machines.

Virtual Reality Beyond the Headset

For their presentation, the up-and-coming video artist Trisha Baga and longtime new media tinkerer Mike Woods of White Rabbit VR delivered a constellation of ideas relating to the human body within the burgeoning field of virtual reality. Sure, there’s the potential for visceral sensation in these virtual worlds, but there is also the lingering question of how (or whether) your good old meat-body will be incorporated into the coming VR revolution.

The pair pointed out some problems with the technology as it exists in 2016: motion tracking systems are neither advanced nor affordable enough to reliably reproduce your body within a VR environment, and wearing a VR headset puts you at risk of pranksters, walking into walls, and looking like a dolt. On the other hand, the total emersion that makes these devices so difficult to walk around in also allows for never-before-seen kinds of embodiment across physical/digital realms. For example, Baga and Woods proposed a new way of thinking about theatrical productions, where audience members’ become actors being fed lines and cues in real time through their headset.

The promise of VR thus far has been in transporting your awareness to a different realm, but perhaps its real potential is to make you act (both literally and metaphorically) in unexpected and novel ways.

Oversharing as Art Form

Far and away the best, most moving project to come out of Seven on Seven was the work of Miranda July and Paul Ford, two writers who share a strong interest in new technologies as a means for personal connection rather than alienation. July, for her part, launched a messaging app called Somebody several years ago designed to foster dialog with strangers by having unfamiliar intermediaries deliver messages IRL, while Ford writes regularly on tech for outlets like Medium and The New Republic when he’s not programming new apps for his business Postlight.

Before the event, they aquired the guest list of registered event attendees and compiled a detailed database of the members’ information through social media and Internet research. They then assembled these facts—ranging from birthdays, addresses, and phone numbers to descriptions of dreams, photos of meals and sunsets, and more idiosyncratic and otherwise personal details—into a second-person prose poem of sorts, addressing the audience members as a collective “you.” (It was, for all intents and purposes, the inverse of Wortham and Junglepussy's Patch.)

A delivery like this runs the risk of coming off clumsy, corny, or creepy, but July and Ford’s deft touch make their project a genuinely moving meditation on the all-too-familiar subjects filling our newsfeeds. Seen as a whole, the stuff we share on social media—banal as it often may be—is, for better or worse, the stuff that fills our everyday lives, with all the complexity, pain, boredom, and subtle beauty that effort entails.

Formatted in this way, the oft-decried “oversharing” unique to contemporary digital culture comes off as almost romantic, epistles to all of our friends driven by the most human of desires: connection and recognition.