It’s easy to forget that many of the artists associated with so-called Post-Internet art are also fascinated with advances in technology that aren’t explicitly digital, from drones and robotics to genetics and bio-sciences.

The Los Angeles-based artist Max Hooper Schneider, for instance, makes sculptures that are informed by landscape architecture and biology. The only thing “Post-Internet” about them, really, is their interplay between variety and specificity, which suggests that he has internalized the web’s remixing sensibility as well as its unprecedented ability to deliver obscure items to his studio doorstep. Whether coating a Mongolian mountainside in phosphorescent paint, filling a refurbished popcorn cart with live snails, or using sound-reactive LED lights in performance pieces, Hooper-Schneider looks to the unexpected juxtaposition as a way to “un-quantify the world.”

Aiding him in this task is his home-brewed phosphorescent material, a high-concept science experiment that pops up in several of his works. The glowing material harbors photons while in light and emits them in darkness; Hooper Schneider compares it to “a pet you feed with light.” In his Glowing Beluga Whale Skeleton (2013), made by casting molds of a beluga whale’s bones in a specially made combination of a rare photoluminescent substance and resin, he uses it to illustrate his “animist” beliefs (the notion that all things, organic or otherwise, possess a kind of rudimentary consciousness).

Glowing Beluga Whale Skeleton, 2013 (photo by the Pacific Design Center).

Glowing Beluga Whale Skeleton, 2013 (photo by the Pacific Design Center).

The lists of materials for Hooper Schneider’s works are often as telling as their installation shots. (One might compare him, in this regard, to Josh Kline.) Consider Genus Watermeloncholia (2014) from his show at Jenny’s gallery in L.A., which consists of “bioengineered square watermelon, glass cube aquarium, UV electrolyte bath, soil, actinic light fixture, plastic ports, copper wire, battery operated digital sign.” The work fuses altered organic materials with newly-accessible technologies and adds a splash of humor to remind viewers that these kinds of pseudoscientific experiments are meant to be fun.

Genus Watermeloncholia, 2014 (photo by Jenny's, Los Angeles).

Genus Watermeloncholia, 2014 (photo by Jenny's, Los Angeles).

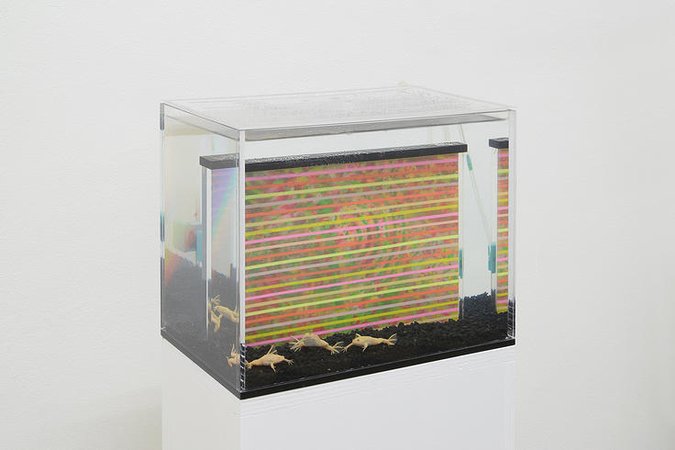

Hooper Schneider also makes extensive use of live animals, such that pet shop staples like beta fish, red-eared sliders, and fiddler crabs become central to many of his works. These creatures (which Hooper Schneider refers to as “faunal ready-mades”) are utilized primarily for their formal qualities, as in Pierre Huyghe’s Zoodram series in which the French artist places various undersea crustaceans together to create dramatic yet utterly alien scenes that play out in the confines of a dimly-lit aquarium.

Albino Clawed Frog-Tetra System, 2013 (photo by Alessandro Zamblanchi).

Albino Clawed Frog-Tetra System, 2013 (photo by Alessandro Zamblanchi).

Hooper Schneider’s pieces function as extensions of our ordinary relationship with these animals as, essentially, aesthetic objects, placed on a desk or on top of a counter to serve as moving eye-candies. We see this impulse in pieces like Albino Clawed Frog—Tetra System (2013), which has the vertebrates sharing a small tank with one of his distinctive, cell-like acrylic paintings such that the forms of each class of inhabitant (fish, amphibian, artwork) blend together into an almost cohesive whole. His most recent work Utopia Banished (which is currently attracting stares at High Art’s booth at Liste) takes a similar tact, pairing live leeches with a porcelain wedding cake in a vitrine.

Utopia Banished, 2015 (photo by High Art, Paris).

Utopia Banished, 2015 (photo by High Art, Paris).

In each case, we’re left wondering where the piece is really taking place: in our minds or in those of the small creatures that compose it. We suspect Hooper Schneider would answer “in both, and in so many more too.”