Although Tate Modern’s new Agnes Martin show is a chronological retrospective, it opens with a room of later works by the American abstract painter. Here, curator Frances Morris has installed Martin's diluted grids with the aim of both acquainting visitors with the quintessential Agnes Martin and reminding them to slow down and get into the mode of sustained looking before beginning a dutiful procession through the show.

It’s a good way to start. Although Martin, like many artists, disliked talking about her technique, when she tried to explain the all-encompassing grid in her work she did so in poetic, almost spiritual, terms—she’d be thinking of a tree, she said, but the image of the grid would just present itself in her mind.

Yet as the images below reveal, behind this atemporal, persistent vision lay many decades of preparation—serious engagement with both the business and the history of painting, not to mention the technical application required to pull off her extraordinary feats of restrained emotion.

Mid-Winter (1954)

In this early painting, Martin is clearly looking at European modernism through the filter of a previous generation of American abstract painters—artists such as Arthur Dove and Marsden Hartley. Although it’s quite unlike her later works, you can see in it the emergence of her combination of line and wash. Her lines appear simultaneously drawn and inscribed, as in her signature grids.

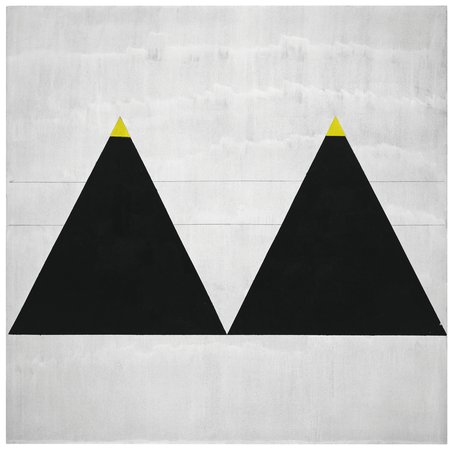

TheGarden (1958), Burning Tree (1961) Untitled (1962) and Water (1958)

This grouping at the Tate highlights Martin’s early attraction to geometric forms such as squares and triangles, which became more precise when she moved from the desert to New York. These works were made in the laboratory-like New York loft space where she worked alongside Jack Youngerman and Jasper Johns. With the advent of Pop, Martin and her studio-mates were starting to look for a way out of the Abstract Expressionism that had become de rigueur in the city. She suspended her practice as a painter to work in three dimensions with found objects and a more geometric distribution of form. Morris, the show's curator, believes these "ready-mades" helped Martin get to the grid.

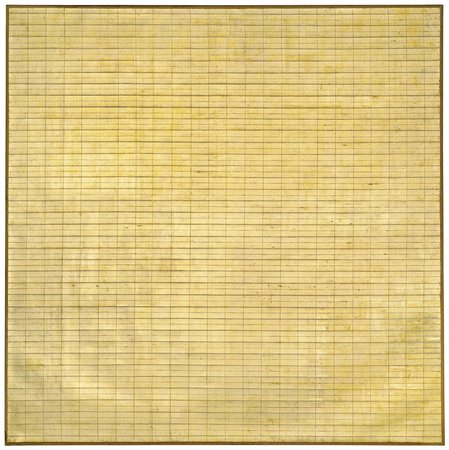

Friendship (1963)

During her time in New York, Martin began her struggle with schizophrenia and was briefly hospitalized. In 1963 she returned to painting, creating labor-intensive, large-scale canvases characterized by their repetition. Most measure 72 by 72 inches, a little bigger than human-size. Working with gold leaf on such a scale was most likely very difficult. These works herald, for Martin, a new and different language of touch and gesture.

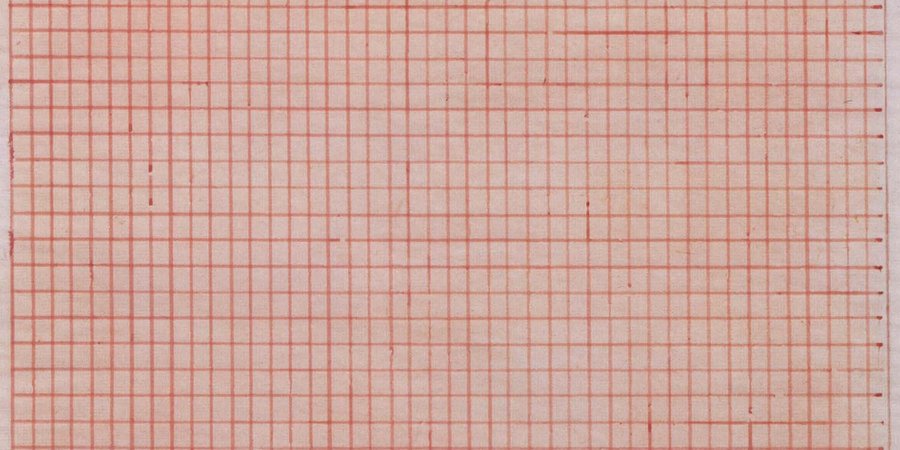

The Tree (1964)

This painting, one of a series of muted pencil grids, is Martin at her most rarefied and minimal; her lifelong friend and dealer Arne Glimcher has likened experiencing these works to “breathing in air." The process of making them was not so effortless, however. Martin would see the painting in her mind, sketch it out at the scale of a postage stamp, and surround it with complicated mathematical calculations designed to get her to the 72 by 72 inches finished article. Then the image would be transferred onto the canvas using Scotch tape, a ruler and a pencil. Only after the grid was established would she mix her liquid paint, applying it with quick gestures. Films of her at work show her moving up and down the canvas from top to bottom, rotating it only when she was finished.

Untitled #1 (2003)

In 1990 Martin moved to an assisted living center in Taos, New Mexico, and her art became bolder and more dynamic. Her paintings shrank from 72 inches to a more manageable 60 inches, and she introduced more exuberant color. After three decades of working within the self-imposed restraint of the grid, she experienced a profound shakeup—one that came not from doubt, but rather from extreme confidence.