“Eric is anything but a bad boy,” joked the estimable art-world wit Jane Kaplowitz when she saw me carrying around a review copy of Eric Fischl’s new memoir Bad Boy: My Life On and Off the Canvas. Her take was archly comic, but it revealed a multileveled truth. Not only is Fischl one of the celebrated American painters of the 1980s, but by most accounts he is a generous friend, a devoted husband, and a serious artist. His intelligence and dedication, as well as his modesty and good sense, come through on every page. In short, Jane is right: he’s not such a bad boy at all.

The book, which the artist wrote with Michael Stone, takes its title from his notorious paintings of taboo suburban drama that made the art world swoon in the early 1980s, including one titled “Bad Boy.” This intense picture shows a naked woman sprawled on a bed, her legs spread and head thrown back in some erotic transport, while a young boy stands watching her, his back to the viewer, as he reaches surreptitiously into her purse. (I prefer to think of it as Fischl’s Demoiselles d'Avignon, since it has a bowl of fruit in the foreground.)

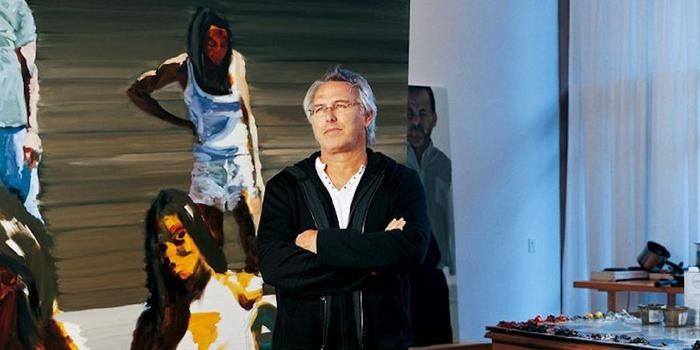

This kind of psychosexual frisson has become something of a cultural commonplace—consider Rick Moody’s 1994 novel The Ice Storm, for instance, or the artist Steve McQueen's 2011 film Shame—though no one quite reaches Fischl’s heights, and in contemporary art the theme still belongs to him. His ‘80s paintings have improved over the years, and are emblematic of their era. Time has transformed the crudeness of his style (Fischl himself modestly confesses that early on his “painting skills were questionable”) into something authentic and authoritative. And his signature artistic vision, it’s worth remembering, remains provocative, as demonstrated by the right-wing fuss that greeted his nude bronze sculptures commemorating both Arthur Ashe (2000) and 9/11 (2002).

What does a reader want from a memoir by an ‘80s art star? Gossip or studio talk? Career tips or cultural history? I think we hope to have all the secrets revealed, trivial and profound together. In other words, as Paul Gauguin might have put it, “Where do we come from, what are we, and where are we going?”

Fischl is an artist first and last, and the book contains much on his struggles with his art, his artistic insecurities and ambitions, and his thoughts as he developed one series of paintings after another. Especially good are his capsule discussions of the art of his friends, colleagues, and competitors—people like Andy Warhol and Francis Bacon, David Salle and Julian Schnabel, Damien Hirst and, with special sweetness, his wife, the painter April Gornik. Several of these people, along with his brother and two sisters, contribute brief remarks or anecdotes that punctuate the chapters.

Which is not to say that the book doesn’t have its share of juicy stories. Along with mentions of “celebrity” friends like Mike Nichols, Steve Martin, and John McEnroe (to whom Fischl gave drawing instruction) is plenty of grist for the gossip mill. These tales are treated economically and without sensation. Fischl was so upset by Tony Shafrazi’s 1974 attack on Picasso’s Guernica, for instance, that when the reformed art dealer approached him for a group show in 1981, Fischl declined. He only relented on the condition that Shafrazi promise to publish a formal apology for his act. “I’m still waiting,” Fischl writes.

Artists might want to peruse the book for some tricks of the trade. Fischl tells of a negotiation over the sale of a painting to the collector Edward Downe, Jr., who would later be nabbed for insider trading. The price was $2,500, and Downe asked for a discount. (They always ask for a discount.) Fischl refused to budge, saying, “I think the $500 means more to me than it does to you.” Downe laughed, and this time, the artist's hardline worked.

Another tale involves a set of forged “preparatory studies” for Fischl’s earliest paintings, which came to light when one was scheduled for a 1996 auction at Sotheby’s London. “It was my image, all right, but I couldn’t remember making it,” Fischl writes, with amusing understatement. In what now seems to be a familiar tale, the fakes had first surfaced years earlier at a smaller Berlin auction house, from a seller whose father had supposedly visited Fischl in his New York studio and bought several works at once. “It was all hokum, of course,” he writes. “There was no father/collector, there had been no studio visit, and there certainly was no gross purchase.”

And though neither critical praise nor curatorial honors are given much attention in Fischl’s story, you can read the book and discover the cause of his falling out with critics Roberta Smith and Jerry Saltz. It turns out that Fischl gave Saltz his first big break as a writer, hiring him to co-write Sketchbook With Voices—"a kind of texbook survey was doing... about the artist's process." Later, Fischl made Saltz and Smith the subject of what he calls his "first portrait," a "revealing and honest" view of the powerful art-critic couple. "Neither Jerry nor Roberta was comfortable with the way I portrayed them," the artist writes. "I don't think that is what precipitated our falling out, but it didn't help. Perhaps they felt like I'd given them a bad review."

Unsurprisingly, the intensity of Fischl’s narrative paintings of family discord is derived from his own upbringing. As a young man he was troubled, angry, funny and insecure. Born in 1948, he grew up on Long Island’s North Shore in a dysfunctional family, the second child of four. His mother was an alcoholic who committed suicide, and his father a salesman who sounds like he was beaten down by life. Several of Fischl's pictures depict scenes from his own youth.

In retrospect, his path seems almost predestined—the perfect story for a “top dog” of the ‘80s art scene. His youthful searchings included experiments with drugs, orgies, and multiple girlfriends, and took him to both Chicago and Haight-Asbury. He studied at CalArts and taught at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax, both touchstones in 1970s art academia. He arrived in New York in 1978 and worked for Hague Art Delivery and hung out at the Odeon in Tribeca. He exhibited first with Edward Thorpe Gallery and then Mary Boone Gallery, ending up with a mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum in 1986. He was right there for the ‘80s art boom, which he aptly characterizes as a wave that prompted a "feeling of being swept up and carried by something so much bigger and more powerful than yourself.”

Along the way, Fischl more or less admits that he doesn’t have the answers to Gauguin’s questions. The “creative process” is “baffling and unpredictable,” he says, and admits he “never understood the business side of art.” The New York-centric art world is “corrosive,” and shot through with ambition and competitiveness. It’s hard to avoid feeling that the ultimate measure of value is the market. These observations ring true. In the end, Fischl finds a certain degree of serenity in the convergence of life and work that characterizes his most recent paintings—portraits of friends and family in happy surroundings.

Walter Robinson is an art critic who was a contributor to Art in America (1980-1996) and founding editor of Artnet Magazine (1996-2012). He is also a painter whose work has been exhibited at Metro Pictures, Haunch of Venison, and other galleries; he recently had a critically acclaimed show of new work on view at Dorian Grey Gallery in New York's East Village. Click here to see his previous See Here column on Artspace.