One of the most accomplished curators anywhere, Hans Ulrich Obrist has devoted his life to the pursuit of a categorical understanding of the artistic tendencies of his time, both in his role as what he calls an “exhibition-maker” and as a kind of human archive of art-historical knowledge. This ambitious endeavor was first begun in his teens through two formative studio encounters—one with the brilliant, omnivorous painter Gerhard Richter, the other with the arch conceptualists Fischli/Weiss—and has stretched out over the ensuing decades to encompass visits with thousands of artists and curators around the world, many of which he has recorded and published in his books.

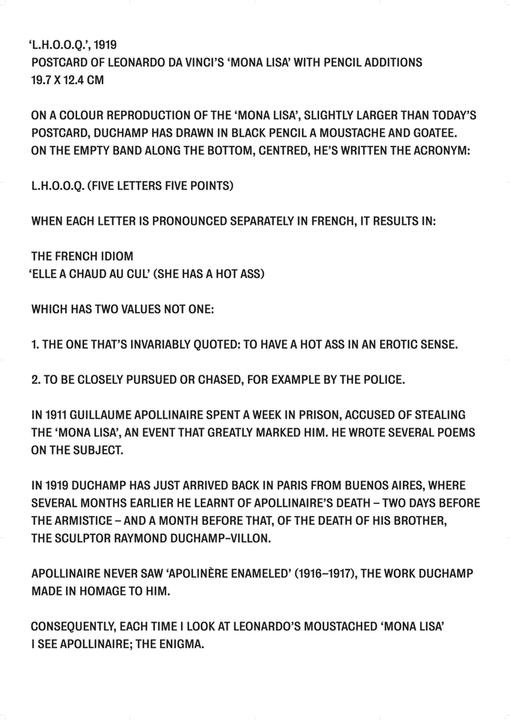

He has also seen tens of thousands of exhibitions, filtering these into his own curatorial projects (which started with a show in his student kitchen during art school) that he now carries out at artistic director of London’s Serpentine Galleries, as well as through various other outlets that include 89+, a joint initiative with Google and Swiss Institute director Simon Castets to showcase work by artists born after 1989. In organizing these exhibitions, Obrist aims to find an intellectual structure—which he terms “the rules of the game,” a nod to Marcel Duchamp’s quote that “art is a game between all people of all periods”—that can make sense of where the art of his time is going, according to his fulsome research. He is also interested, as a curator, in the notion of quantums, or in other words the bare minimum that an artwork needs to do in its medium to be considered an artwork.

Since his visit with Richter, which started a friendship that led to multiple collaborations on books and exhibitions, Obrist has spent a good deal of his curatorial energy investigating the state of painting—an art form that, compared to his work in other cutting-edge media, could seem old-fashioned. Now, as one of the nominators for Phaidon’sVitamin P3 compendium of new directions in contemporary painting, he has helped assemble a survey of the medium’s sweep today. To find out where painting is going today, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Obrist about what he sees as novel potentials for the ancient art form.

Paintings are often the way that people are first seduced into a fascination with art. I believe it is a similar story with you, since you began collecting postcards of famous paintings as a child and, rather precociously, curating them into miniature exhibitions. How did you get the idea to do that?

I suppose it was actually initially sculpture that was the initial trigger, because I remember when I was maybe 9 or 10 years old we went to the Kunsthaus Zürich, and I was magnetically attracted to those long, thin figures of Giacometti. That was really my gateway into art, so to speak. But then, it’s true, soon my interest turned into this idea of basically putting together an imaginary museum where those postcards of paintings would be connected to one another.

I think this had to do with a game I loved to play with friends as a child where you would have these postcards and you’d cover them, and then, little by little, uncover a millimeter square, two millimeters square, then three millimeters, and your friend would have to guess the painting from what they could see. So, this was a kind of passport to an idea.

But, you know, while history happens in museums, for me the first true encounter with paintings was when I was 17 and I went to the exhibition of Gerhard Richter at the Kunsthalle in Bern. Richter was present, and I was extremely mesmerized by seeing the paintings there and also by seeing the many different parallel realities in Richter’s abstract paintings, Richter’s photo paintings, Richter’s glass mirror works, and Richter’s oscillation between figuration and abstraction. This encounter with Richter led to a studio visit later that year when I then travelled to Cologne and met Gerhard there for the first time.

Richter is an ideal point of entry into painting because, as you said, his work in many ways encompasses this entire history of the medium, from virtuoso realism to abstraction and the extreme minimalism of his mirror works. How did you go from this studio visit to organizing a show of his work at the Nietzsche-Haus, the summer home in Sils-Maria where the philosopher worked on Thus Spoke Zarathustra?

Everything was there. There were the mirrors, and there were the photographic paintings that were always parallel—even in the moment of his ‘80s abstraction there were always photographic paintings as well—and there were also the oil-painted photographs. These became the subject of the first paintings exhibition I organized, which was the exhibition in Sils, a town in Switzerland that’s connected to my childhood, where I grew up. There are these mountains there, and Richter continuously took photos of them and partially repainted them, and they would just become part of his Atlas [Richter’s personal archive of studies and other materials related to his oeuvre, now published as a book]. The exhibition was the first time that he actually showed them as autonomous works.

In Richter’s repainted photographs, there is a level of photography conjoined to a level of the realities of painting, and it’s interesting because, in a way, all these categories are dissolved. On the one hand, we see the form of the photographic landscape, but it seems to be wrong, due to this addition of paint. All of a sudden, painting on photography assumes this unmarked position. And it’s kind of interesting that these splashes of paint represents as much of reality as the photographic base on which they appear.

It was all about doubts about the medium and, yet, a belief in the medium. It was an oxymoron, extremely contemporary while at the same time extremely traditional. So I was super fascinated by that, and by the multidimensionality of Richter’s paintings—they’re like super string theory, with so many dimensions at the same time. It was something else. As you said, it was almost the perfect entry into painting, in a way.

So would you say you were mostly attracted to the intellectual aspects of painting—the way his work was opening the door to new potentialities for the medium—rather than the technical laying down of paint and its other formal material qualities?

Yes, I think it’s an interesting question, because the other studio visit that influenced me at the time was with Fischli/Weiss, when I watched The Way Things Go. But my interest wasn’t only conceptual. I have very strong memories of these two first studio visits, and with Gerhard Richter it’s never purely conception on its own—it’s always both. There is an ambiguity.

Then, through this visit, I became very interested in thinking, “Where is painting now? What’s happening in painting?” Because, growing up in the early ‘90s, my generation was mostly involved in a big questioning of the object, questioning painting, but I finally felt through Richter that, you know, maybe it would be interesting to do a kind of cartography of painting.

So I started to do hundreds of studio visits—hundreds and hundreds of studio visits—and in a way that crossed all generations. And that research came to the attention of Kasper König, who I had met at a dinner. Kasper and I had actually first worked on a book about public art, and while we were working on all kinds of public art theories, on the social contract of art, we realized that, as a matter of fact, there was still painting.

Then we realized that there hadn’t really been a survey where one could actually consider the potentiality of painting in the early ‘90s, and thought it would be interesting to do that. Everyone knew that in the ‘80s there was “A New Spirit in Painting” [the title of a influential 1981 group show of Transavanguardia, German Neo-Expressionism, late Picasso, and Americans like David Salle and Julian Schnabel at London’s Royal Academy], and that had to do with a new kind of figuration.

But we had realized that what was happening in painting was much more an oscillation between figuration and abstraction. So we thought it would be interesting to do an exhibition where we showed these different positions, but not as a staged show—in the ‘80s there were a lot of staged shows, like Kasper himself had done “From Here Out” [a 1984 survey of “two months of new German art”]—but rather as a quite nonhierarchical exhibition where it would just be a couple of paintings by each artist.

You’re talking about the 1993 exhibition you did together at the Kunsthalle Wien, “The Broken Mirror: Positions in Painting”—how did that show come together?

Of course, this was my first large-scale exhibition. I had just done small shows like the Nietzsche-Haus, and suddenly I found myself with hundreds of paintings, and having to install them in a physical space, and I learned so much from Kasper and his vision. And, you know, the explosion of painting had happened a long time ago and the rules of the game had been set, from the idea of painting to the actions of Allan Kaprow—all of that had happened. But, then, in a way, actually going against the rule had also become, in a way, the rule, and so I became interested in this place where the rules of the games would be sort of typically questioned, but where actually a painting would still be a tool or a model, even if maybe an unpredictable model.

So we did two years of research, and gave it a twist. It was a completely open field because, in the ‘90s you had a kind of splintered reality, where there were mostly singular positions with a kind of locality and yet at the same time with a very high degree of information. There was a polyphony of seemingly decentralized figures in all these different cities, and it was the beginning of an awareness of the collision of centers. So we went to many many places to look at paintings, and we also wanted the show to be trans-generational. We had this idea to do a catalog that would not be alphabetical but instead chronological, from the oldest artist to the youngest, so in a way the book would map different generations.

Who did you include in the show?

It began with Eugène Leroy, who was then still alive, and I remember having visited him and marveling at the incredible physicality of his very, very, very thickly painted canvases, which I could barely carry when he asked me to move them in the studio so that we could see them. Then it went from this deeply physical experience to the complete opposite, which is Agnes Martin, whose most recent work then had been painted two or three years earlier. And then we also had Maria Lassnig, who was forgotten at that time, so we wanted to do a revisiting of her work and invited her to develop a kind of mini-retrospective.

Also, we had Leon Golub, who did his large, partially untreated canvases, and then we went from Arnulf Rainer to [Gérard] Gasiorowski, to Raoul De Keyser, who was then still alive and making these amazing abstract paintings, to Robert Ryman, to Malcolm Morley—from conceptual to abstract to figurative—to On Kawara, to Gerhard Richter, who reunites all these dimensions, to Dick Bengtsson, a tricky forgotten Swedish artist who died young, to Ed Ruscha, to Niele Toroni. Then Georg Baselitz started a new chronology from himself to Mary Heilmann.

It was a sort of protest against forgetting. We wanted to show younger artists alongside artists of previous generations, and the show was really, how shall I say, my immersion into painting—because, as you can imagine, with two years of research it was a real immersion. Also from Sigmar Polke to Edward Dwurnik, to the purely abstract painter Joseph Marioni, to Helmut Federle, to Jean-Frédéric Schnyder, to René Daniels, and then of course there were early works by Marlene Dumas and Luc Tuymans and Albert Oehlen and Bernard Frize, who at that time were in their 30s. So it was a very transgeneration kind of endeavor.

That’s an astonishing array of painters—a real omnium gatherum of approaches. Where did your interest in painting take you after that show?

Around 2000, as time passed, I started to do more solo shows, and I came up with a lot of conceptual shows that were more about “the rule of the game,” and time-based exhibitions too, like “Do It” and “Cities on the Move,” co-curated with Hou Hanru. It was also a moment where I was taking into account the polyphony of art centers, working a lot in Asia, in North America, doing the Dakar Biennale in Africa, et cetera. By then I was the curator at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, doing the program at ARC [the museum’s experimental wing] on the contemporary palette, and my colleagues and I felt that the situation had changed to something very different in the seven years since “The Broken Mirror.”

Because for “The Broken Mirror,” it was still just Kasper and me going all over the world and visiting these painters, but we saw that the ARC program had grown so much and had gained so much complexity and polyphony that it would be kind of weird for just one or two curators to do a survey of painting in 2002. So we took on a much more polyphonic curatorial model, so to speak, and actually invited about 15 curators to curate their own shows within a show, a bit like a matryoshka.

It was an attempt to talk about painting again, and obviously took into account the fact that there were different kinds of painting on all of the continents. So, it became an early show of Beatriz Milhazes, and an early show of Katharina Grosse.

What made the painting in the show “urgent”?

In a way, just the fact that there hadn’t been a survey of in so many years. It was urgent also because of the polyphony. You know, today it makes perfect sense to do a book like Phaidon’s Vitamin P3, where you ask curators from many different cities all over the world to propose artists. In 2002, it was already obvious that this was very important to do, but there was just less information and less knowledge about what was happening around the world. What made it urgent was to introduce all these different positions, in a way.

Painting has always served as a kind of laboratory for innovative ways of looking at the world, from the perspectival experiments of Alberti all the way to Impressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, abstraction, Minimalism, et cetera. Painters often saw themselves as an advance guard, pushing a kind of investigation forward in new terrain. Here, you’ve mentioned how in these shows artists were taking a variety of approaches simultaneously, with figuration and abstraction oscillating and with every sort of style going on at once. I wonder, when you were going through all that polyphony, looking at all these paintings from around the globe, was there any kind of forward progress that you could discern?

We live in a very nonlinear sort of period. So, I think it’s more a jumping universe. But obviously, I do realize there is certainly a progress in a sense, because there are still inventions of new rules of the game. It’s like what David Deutsch describes in his seminal book, The Fabric of Reality, where he talks about parallel realities that exist. I think it’s much more about these parallel realities than a kind of linear progress.

But, at the same time, when we see a work that has not yet been seen in that kind of way, it leads us to where we haven’t been before, and I don’t know if I will call that progress, but there is definitely something happening that is new. There is discussion that nothing new will enter anymore—David Deutsch talks about that a lot in his fascinating text—but I still believe that new things do arrive.

Even in very old mediums. We’re in the post-medium condition, you know, so I think it’s interesting when a new medium arrives, but when television was invented it didn’t necessarily mean that radio was dead. The radio experiments of Nam June Paik were invented in the age of television, you know. In a similar way, I think in the digital age there are a lot of new inventions in terms of painting. It’s fascinating to see how an artist like Laura Owens, or many of the painters in Vitamin P3, reinvent painting for the digital age.

Thinking of painting as a form of technology is a very interesting vantage point, because if you consider the whole sweep of different mediums that artists are employing today—from video and virtual reality to immersive installation and performance—then painting becomes the least optimized medium for avant-garde curators to engage the kinds of crowds that come to biennials and exhibitions. However, when it comes to the market, painting remains the paramount seller because it is, at the end of the day, a remarkably efficient piece of technology. It packs maximum visual power while taking up a minimum of three-dimensional space. No electricity is needed. It’s easily portable, universally readable, effortlessly Instagrammable, and, in some cases, easily resalable. There is a constant, widespread demand for paintings in a way that there simply isn’t for something like video art.

That really happened in 2000, because when we did “The Broken Mirror” in the early ‘90s there wasn’t really a big market, and one could look at paintings without having this full discussion about the market. It wasn’t really at the forefront. It didn’t play a role in any of the reviews, unlike today. But, obviously, later on this difference starts appearing. That’s why I found it very interesting in “Urgent Painting” how a lot of artists revisited the idea of wall paintings, which are basically works that disappear with the exhibition.

When we think about exhibitions, there have to be some rules of the game, or some format on which we hang the exhibition—a kind of dynamic mechanism that allows quantums to be shown, no? And one of these dynamic mechanisms for “Urgent Painting” had to do with artists resisting the idea of a commodification of painting, or resisting the idea of it having an immediate connection to something that is sellable. I think that had to do with this surge of wall paintings and wall drawings. Wall paintings were actually a big part of the exhibition, and once the show ended they were painted over.

Meanwhile, one intriguing way that painters have been keeping up with technology is by directly addressing it, either by approximating its effects, using its tools, or commenting on the new condition it has thrust us into. In Vitamin P3, for instance, you can see this in the work of artists as diverse as Avery Singer, Louisa Gagliardi, and Mary Weatherford. What are some of the more productive ways that painters are taking on our technological world?

I think many artists are making it clear that they are painting in the digital age, and there are actually lots of exhibitions that address that. But I think one of the things that’s kind of an interesting paradox is that, even if that’s the case, paintings don’t move, in a way. It’s something Bertrand Lavier pointed out the other day. He says that everything moves now—everything is in continual transformation—so it’s interesting that paintings just don’t change.

That’s a very big difference, because, for example, one of the great breakthroughs in digital art is the great practice of Ian Cheng that, all of the sudden, video no longer has to be a loop but now can be an algorithm, a complex dynamic system that can evolve and change. If you have a video of Ian Cheng’s in a room, over the next 50 or 100 years this video is going to evolve in unpredictable ways, so you will never have the same film.

So what Bertrand Lavier said is that, as a matter of fact, painting is the only thing where that doesn’t happen. You move, but it doesn’t move, in a way. Maybe, in a moment when everything moves, maybe there is a desire for things that don’t move.

At the Serpentine, you’ve had a very refreshing string of painting shows recently, including spotlights on the imaginary portraiture of the Ghanaian artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and on the installation objects of DAS INSTITUT, the German art duo composed of Kerstin Brätsch and Adele Röder. These are all younger artists who use painting to advance complex positions. What drew you to them?

At the heart of Yiadom-Boakye’s work is an exploration of the ‘mechanics’ of painting. She focusses on techniques, structure, and composition, and by playing with the scale and gaze of her figures she reformulates the visual language of traditional oil paintings. Yiadom-Boakye raises timeless questions of identity and representation in art, drawing attention to the shortcomings of art history.

Brätsch, meanwhile, uses painting to question the ways in which the body can be expressed— psychologically, physically and socially—while Röder searches for basic symbolic forms to create a non-verbal language utilising clothing, posture, and light. As DAS INSTITUT, the artists attempt to communicate the inexpressible—the intuitive, irrational element of human experience and relationships.

You have also featured older painters, from your show of the eminent Lebanese artist-poet Etel Adnan's landscapes to, most recently, a survey devoted to a very famous artist, Alex Katz. What made it important for you to showcase someone like him, who everyone already knows, but who is currently enjoying a burst of vitality in his late-career period, when he is nearing 90?

I mean, it had to do with that—the fact that it’s so impressive that he is doing this extraordinary work now in his late 80s. It actually came out of a conversation I had several years ago with Elizabeth Peyton, where we did a studio visit with her and she said, “You should really visit Alex Katz.” We very often listen to artists, and Alex Katz is an artist’s artist, so then we visited his studio and we were amazed by the work he had been doing.

We were also interested in the fascinating connection Alex Katz has had to poetry since the ‘50s, working with John Ashbury and Frank O’Hara, so that’s why we paired him with Etel Adnan, who is not only a great poet but also a wonderful painter who puts a sort of energy and magnetism into her little paintings and leporello notebooks. Everything is getting bigger and bigger, you know—museums grow, exhibition wings grow, biennials grow—so it’s kind of interesting that she remembers smallness.

The story of Adnan's life is remarkable, growing up in Lebanon with a Syrian father and Greek mother, studying at the Sorbonne and traveling the world as a professor, then returning to Lebanon as an influential activist journalist, all the while making art and writing poetry on the side. What is it that draws you so much to her art?

Her work is similar to Paul Klee, whose work I saw as a teenager and who was an epiphany. He was a painter, a musician, an architect—it’s too narrow to call him a painter. That’s like Etel Adnan, who paints and makes tapestries but also is a poet and an activist, and Klee is her role model. And, like a boat in the ocean, Klee was not directing his painting but rather his painting was directing him, giving him the courage to go into the unconscious and see the terrifying side of human beings. I think that is something very, very important—the idea of going into the unconscious.

And also, hope. You know, Gerhard Richter often says painting is the highest form of hope, and if you look at the way Klee paints these very paradise-like gardens but at the same time the insanity of human beings, he shows us all the directions the mind can go. Picabia said, “The head is round so it can change directions,” and so I think that’s another thing painting can do, to show us these different directions of the human mind.

Adnan is a polymath, and that allows her to cross many dimensions. She was born in 1925, so she’s now in her early 90s, and it was only in the 1970s that she discovered Mount Tamalpais, which became her most important subject—she started to paint it a bit like Cézanne painted Saint Victoire. It led her to stop separating poetry and painting, and to bring them together. Also, if you look at her writings, they’re very often about the war, the apocalypse, but the paintings really radiate energy. They’re so positive, and they inject hope into a very desperate world. So this idea of hope seems to be an important aspect, no?

Speaking of hope, one of the great developments of the past half-decade has been a broad effort among curators to look back into history and recuperate artists, often painters, who had been left out of the official narrative due to their race, gender, sexuality, nationality, or otherwise outsider status. This has given us extraordinary new discoveries, like the late gay Indian painter Bhupen Khakhar, who recently had a stunning survey at Tate Modern, and the ecstatic mystical paintings of Hilma af Klint that you showed at the Serpentine. What do you make of this development?

It just goes to show that just because paintings don’t move doesn’t mean they are still. They’re very dynamic things—they come, they go, they approach, they recede, they disappear—and that’s because they are pure feeling, like a fog or a cloud. But they are also a form of memory. It’s very interesting if you think about painting as memory, because in this age where we have more and more information, having more and more information doesn’t mean that we also have more memory. Amnesia is at the core of the digital age, so I think the continuous practice of painting is also a process against forgetting. But it’s not the type of static memory that very often gets corrupted, it’s the opposite—it’s a dynamic memory, just like how our brain isn’t the only locus for memory but is part of a broader process. So I think painting is very much a protest against forgetting.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Why Does Phaidon's Vitamin P3 Survey of Contemporary Painting Matter?

The Vitamin P3 List: Discover the 108 International Artists Who Are Revolutionizing Painting Today