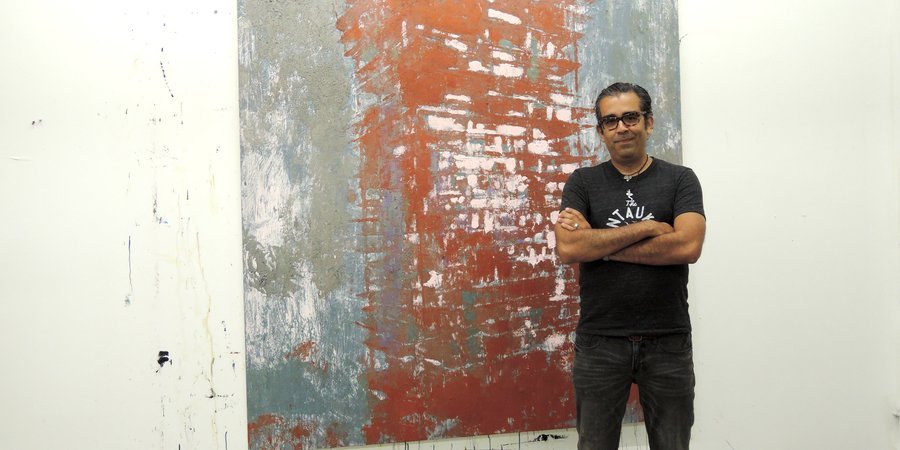

The Puerto Rican-born painter Enoc Perez is best known for his "brushless" paintings of modernist architecture. The process more closely resembles printmaking than traditional painting, and involves the artist drawing an image on one side of a sheet of paper, and coating the reverse in paint. Perez then affixes the painted side to a canvas and traces over the drawing to impress the image onto its surface. The effect distorts the lines into the cross-grained, seemingly weather-worn portraits of old hotels and nude figures that have become his signature.

The work has become increasingly sought-after. In 2010, Perez joined Bill Acquavella's white-glove Upper East Side gallery, and he has held shows at Lever House and the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Now, Perez says he has found the stability and confidence to begin experimenting even further. For his latest body of work, he plans to produce inkjet paintings that will deal with one of the most closely canvassed subjects in art history: Picasso.

Perez gave Artspace's Rachel Corbett a tour of his Midtown studio, where he is currently at work on the new body of canvases inspired by the modern master, plus a series of Swiss architecture paintings for a show next year with Zurich's Thomas Ammann Fine Art, and a book collaboration with the French fashion designer Gilles Mendel.

You are best known for your paintings of modernist architecture, yet the prototype collages on your wall right now are mash-ups of Picasso paintings with your own nudes. Why the change in subject matter?

I always wanted a Picasso, so I made one for my house three or four years ago. Now that I’m 45, I feel like I can go there. You have to have the courage; if you’re going to approach another painter like that you better be damn sure you know what you’re doing. Think about Deborah Kass with the Warhols—those are awesome because she knows exactly where she’s going with that. So the first thing I did was call Richard Prince, because he had done Picassos. So he came to my studio earlier this year and I told him how I’ve always wanted to do Picassos and he said, "Why don’t you do them?” It made me feel good because these are deep waters—Lichtenstein has made some of the greatest Picassos, Richard has made amazing Picassos. So the fact that he said, "do it, man" made me feel really good.

Which Picasso periods are you looking to source material from?

I'm a big fan of late Picasso, but I'm looking at all periods.

Will you produce the works in your signature print-painting process?

I’m going with inkjet for these because I already have the collages made on [the iPad app] Brushes, which is the same one that David Hockney uses. I could literally collage the images on canvas and then paint on top, but if I have the collage made already, why not use it? You have to embrace the technology. Basquiat was out there using color Xerox before anyone else was using it. That's just part of it.

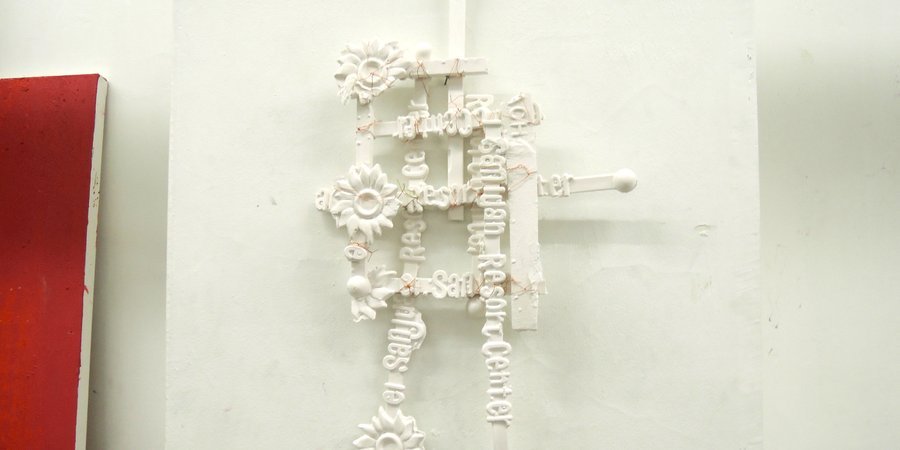

You've left your comfort zone in the past when you made a series of vertical bronze sculptures inspired by cocktail stirrers.

I had been trying to make sculpture for five years, but had never been able to until last year. I have this enormous collection of drink stirrers, an attic full of them, including one from the Normandie [the Puerto Rican hotel that was the subject of Perez's first architecture painting]. So last year I scanned it in 3D and made it a little bigger and made a little collage out of it. I don’t really know how to sculpt, so I called a few friends; I thought I had something in my hands but I wasn’t sure, I couldn’t see the art in it. So my neighbor Bob Colacello came over and said they were good, and I called Peter Brant, and he liked them, and then David Mugrabi came by and said "these are great." And, of course, my dealer really liked them too. In fact, he said, let’s do a show, which I wasn’t expecting.

Do you plan to continue making sculpture?

I’m making more now actually. I just made a palm tree that I will cast in aluminum for my garden because I can’t grow palm trees in the Hamptons.

Your imagery has become increasingly weathered and abstract over the years, partly due to the fact that you recently began using a brush to incorporate your own "imperfections" on the canvas. What inspired the change?

I had been making very figurative paintings before and they were very well resolved, but so well resolved that I don’t think the complexity of it came through. They were made the same way, without brush-use, but they turned out so figuratively perfect. So one day Tony Shafrazi says, "I was looking at your painting in my apartment and, you know what, if you take a loupe and look really close, you can see the struggle." When he got up close, he saw the whole thing disintegrating, but you had to use a magnifying glass. So it got me thinking, maybe if I untangle this matter, not simplify it, but decompose it a little, it'll be more interesting. So I got some brushes, which was kind of like breaking my own rule, I don’t know why—people had been introducing me at parties as the guy who paints without brushes, but who cares? So I started to incorporate brushes and looking at all these abstract artists, like Cy Twombly and Rothko, and I started to relate to the palette.