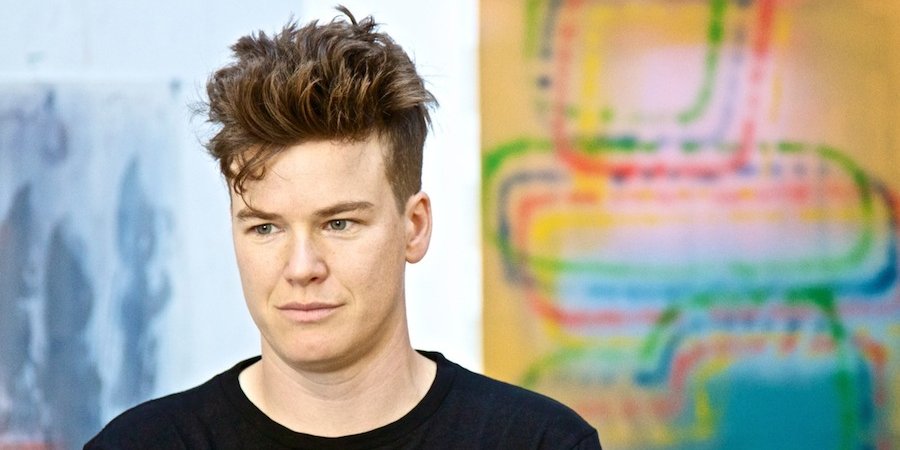

With their spatially ambiguous patches of bright, airbrushed color, Keltie Ferris’s abstract canvases seem to preempt the conditions of digital viewing—the weird vibrancy and transparency of backlighting, the uncertainties of scale and depth. Her scatterings of dots and squares are frequently interpreted as pixellated images, and her aversion to heavy gestural brushstrokes aligns her with Albert Oehlen and other early adopters of screen-mediated painting.

Recently, however, the 38-year-old artist has thrown herself into an insistently physical series of works on paper. The primary tool and subject of these works is her own body; using a messy oil-and-pigment technique gleaned from the “Body Prints” of David Hammons, she has been making process-rich self-portraits that feel simultaneously intimate and in-your-face.

This fall, Ferris’s paintings and body prints will be shown together for the first time in her second solo at Mitchell-Innes and Nash in Chelsea. As she prepared for that exhibition (opening September 9) and two other upcoming shows at the University Art Museum in Albany and Klemm’s in Berlin, Ferris welcomed Artspace's Karen Rosenberg to her Bushwick studio to talk about her embrace of body art and what it means for her paintings.

Photographs by Simon Courchel, except where noted.

Let’s start with the body prints, which are a relatively new development in your work and are markedly different from your paintings in terms of materials and technique. What prompted you to make them?

I was looking for a different kind of emotional engagement with my paintings, because my paintings are so declarative and performative. They’re emotionally bombastic, and I wanted to make something more intimate, quiet and personal. I’ve always wanted to touch the paintings more, in contrast to the spray paint, and to bring those techniques into collision.

A couple of years ago, after the Jasper Johns “Gray” show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I came home and did a couple of more Yves Klein-esque body prints in paint on canvas. They were too melodramatic— that’s never been the emotional tenor that I’ve been interested in.

I was looking for a way to do body prints that didn’t have this melodrama, which it does with paint on canvas Yves Klein-style. When I saw the David Hammons body prints a few years later, I thought: That’s the key.

What was it about the Hammons prints that inspired you?

Klein wasn’t using his own body—he was using other people as tools. I’m using myself as an imprint mechanism. So I think I’m much more aligned with Hammons. When you’re just using yourself, versus a bunch of naked women and you’re a clothed guy, it’s a totally different endeavor.

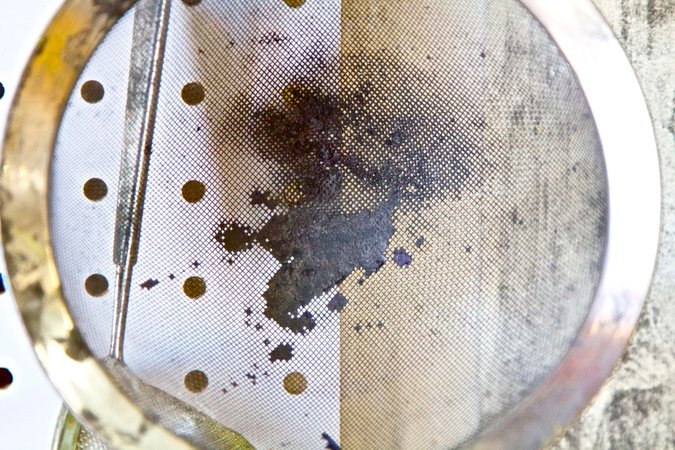

What kind of process do you use?

My process is 100 percent from Hammons. As far as I can tell he and Johns were the only ones who have done this particular method, where you douse yourself in edible oil—Hammons used butter and cooking oil, I use vegetable oil—and you put yourself on paper, and the paper absorbs the oil. And then you have to find a way to move pigment across the canvas, and it sticks, mostly, to where the oil is. It’s a two-step process.

It’s also interesting because you’re making paint through the image—paint is oil and pigment, and those two things are coming together in the work.

How have the body prints evolved? The ones in your show at Chapter NY last year were largely black-and-white, but the new ones are very colorful.

I started off exclusively doing one print at a time on paper, and using one color. I gravitated to graphite powder because it has subtle variations of greys within it, so it makes the figure a little rounder, more three-dimensional feeling and less like a stamp.

I’m trying to add variation to the work as slowly as possible. Sometimes I have more bodies per paper, and I’m bringing more color into it.

It seems significant that you’re using your clothed body. You can see the creases and seams of your jeans and button-downs.

I did some nude ones at the very beginning. I had to do that almost as a dare—could I put myself out there in that way? Now, I just do me in my studio clothes. I don’t want to put any props or other objects in—I don’t want to style them. I want it to be just me and what I wear in the studio. I want them to function as portraits of the artist.

They’re also performances of a kind.

All painting is performative. There’s the romance that this is done by one person, alone. I’m hoping that my body prints will make that performance real, and literal, and unmistakably here and now.

There are some new developments in your paintings as well—for one thing, you seem to be experimenting with scale. For a long time, you worked in an 80-by-80-inch square format. Some of the works you’re showing this fall are much larger; others are quite small.

In L.A., I was able to have a studio that’s three times as big as the one I have here. And I was able to have a separate spray room. In this one, I can’t back up; I’m constantly moving the paintings in and out. Out there I was able to make really big paintings and work on small paintings side-by-side, so I had a clear sense of a series—to have them in the spray room next to each other. That enabled me to make more small works that were related to each other, and also to make large works.

I’ve always wanted to have more variety in that regard. I love small paintings, but big paintings are easier for me because I’m an athletic, bodily person. It’s almost easier for me to make a big painting than a mid-sized painting.

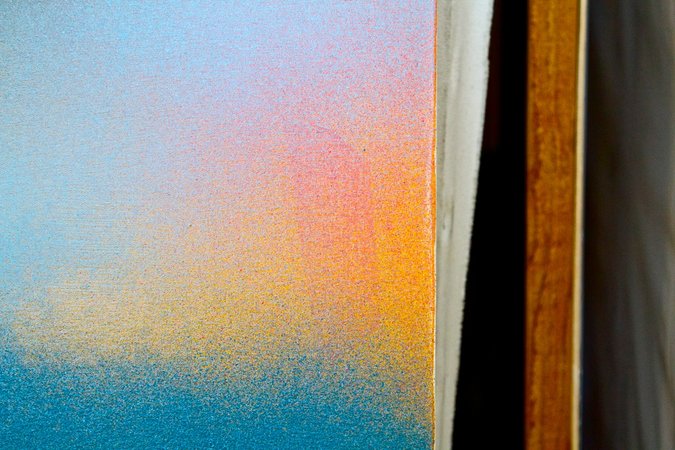

The biggest of the new paintings also feel more atmospheric, with large, hazy, spray-painted areas.

About three or four years ago, my paintings got extremely dense and layered. In the last three years or so I’ve been pulling apart all the pieces. I was originally interested in spray paint because it’s a found, mechanical mark. I think that discussion has played out—I think I added to it, but that conversation has completed itself.

Maybe I’ve been indulging my propensity for color, and how those colors layer and overlap—the haziness of two layers under each other. That’s a more timeless conversation.

Do you think that conversation around spray paint and mechanical mark-making has really played out, at a moment when Christopher Wool and Albert Oehlen have so much influence on younger painters?

I feel like Christopher Wool is so influential, he’s almost like our de Kooning right now. Everyone’s copying him, or riffing on what he’s brought to the table.

I think the Oehlen show [at the New Museum] is more where my soul is—I really love the wildness, the unpredictability of his work. And those black-and-white paintings, the computer paintings, kill me. It’s almost depressing when you see work like that. There are so many paintings in there that I know from books. They’re like your own private love affair, and then when you meet them in person you’re a little disappointed just because they aren’t exactly what you thought they were. I feel like I’m still struggling with that.

Who are some other artists you’ve been thinking about?

That Frank Stella book Working Space was mind-blowing as an undergrad. He’s the only person who can write about composition in a way that’s exciting. His idea of how a space can stretch, or bulge, or come forward, is the heart and soul of constructing a painting. It’s such an enjoyable read, especially the part on Caravaggio—because of that book, I went and saw as many Caravaggios as I could in person. That’s where I got this idea that all painting is historical but all painting is alive, currently.

Matisse is a more recent influence. There’s an element of my work that aspires to his joie de vivre—how do you do that and not have it come out candy or trite or sickeningly saccharine? With Matisse you can almost forget that there’s imagery. I feel an aliveness and sexuality that’s not piggish, compared to Picasso.

You studied with Peter Halley, while getting your M.F.A. at Yale. What did you learn from him?

He had some really interesting ideas about texture and image in painting, and how this is a textured object, which is another way of saying handmade. The difference between cheap clothes and expensive clothes is the fabric, how it hangs, how it touches you. You want to touch it and feel the gorgeousness. He would talk about how every corner, every inch, of the painting has to be equally loved.

You have your own strong ideas about the role of touch in painting.

I do think there are materials and tools that have really clear allegiances, ideologically speaking. There’s a huge interest in printmaking and painting without touching, painting by extrusion. Whereas a brush is like a touch-felt mark. It’s about whether you emphasize that handmade quality or this futuristic, mechanical computer-made painting.

Maybe ultimately I’m talking about the timelessness of painting, the fact that you look at a van Gogh and it was made 150 years ago and it is now what it was then. The object itself was touched by van Gogh, and that’s part of his magic. My goal is to have that feeling of future and that feeling of distant past. Maybe I’m trying to have my cake and eat it too.

A yet-to-be-titled work by Keltie Ferris, 2015. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 96 by 130 in. (243.8 by 330.2 cm.) Courtesy Mitchell-Innes and Nash.

A yet-to-be-titled work by Keltie Ferris, 2015. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 96 by 130 in. (243.8 by 330.2 cm.) Courtesy Mitchell-Innes and Nash.

Even though you like to talk about van Gogh, people often interpret your paintings as being about digital space.

That’s there, that conversation. The recurring mark that builds up through a grid can relate to textile design or Post-Impressionism, but it also goes towards video games and the digital.

My paintings have a push-pull. Everyone always talks about things that seem far away are coming forward. My newer body prints maybe have some of that too—that watercolor is underneath, but everyone thinks it’s on top.

Keltie Ferris, Jack, 2015. Oil and powdered pigment on paper, 40 1/8 by 26 in. (101.9 by 66 cm.) Courtesy Mitchell-Innes and Nash.

Keltie Ferris, Jack, 2015. Oil and powdered pigment on paper, 40 1/8 by 26 in. (101.9 by 66 cm.) Courtesy Mitchell-Innes and Nash.

What other connections can we make between the body prints and the paintings?

The paintings have a mojo of their own, a vitality that almost seems separate from me. I am there, but they have their own agenda—it’s almost like they make themselves. It doesn’t feel like it’s about me at all.

The irony is that everyone wants to know who I am—am I a woman painter, am I a gay painter, am I middle-aged now, am I young? They’re asking all these selfhood questions, whereas the paintings almost seem like complete people in themselves. The body prints were my way of saying, “Well, if you need me, here I am.”