Earlier this month in our second installment of The Other Art History (where we “re-write” the history of an art movement to include under-acknowledged artists), we wrote about the non-western women who contribute postcolonial feminist perspectives to the movement of Feminist Art. Shirin Neshat was at the top of the list.

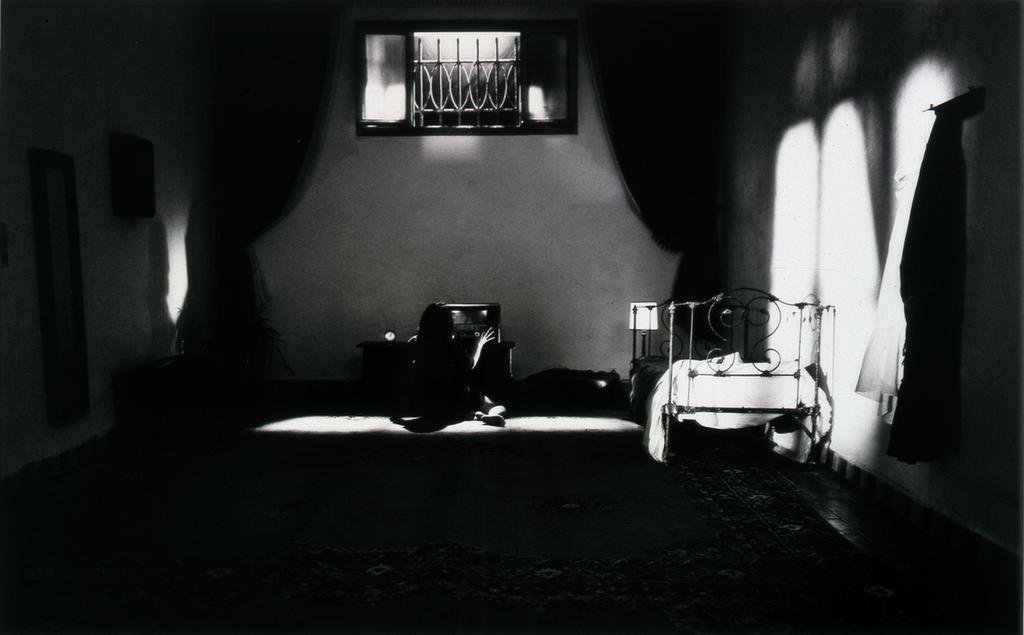

Now banned from even visiting Iran, where the artist was born and raised, Neshat is a photographer and filmmaker known for addressing the nuanced social and cultural codes of Muslim societies, especially in relation to femininity. (She sold the first piece from her Women of Allah (1993-1997) series to feminist art legend Cindy Sherman , if that's any indication of Neshat's resonance.) Later Neshet began experimenting with film as well, and in 1999, she was awarded the Venice Biennale’s Golden Lion award. (Neshat is also the recipient of The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize, was named the "Artist of the Decade" in 2010 by Huffington Post , was photographed by Annie Leibovitz for a calendar celebrating the world's most inspiring women, and has shown her work at the Whitney, Walker Arts Center, Detroit Institute of Arts, Dallas Museum of Art, Art Institute of Chicago, among many others.) In 2004, she began working on a feature-length film based on Shahrnush Parsipur’s novel Women Without Men . The film, described by the New York Times ’ Stephen Holden as “visually transfixing,” profiled four women living in Tehran during the American-backed coup that in many ways signaled the beginning of anti-US sentiment in the Middle East.

In this 2006 interview with Kathy Kubicki for Phaidon’s Speaking of Art by William Furlong, Neshat talks about working on Women Without Men , and her own tenuous relationship to her home country.

Let’s talk about your [2005-2006] shows in Amsterdam, New York, and Berlin. First, could you say a little bit about how you arrived at this work?

Actually, for the past four or five years I have been very busy scripting a book into a feature film, which will be a very big transition for me. This is a book called Women Without Men written by an Iranian author, Shahrnush Parispur, in the early 1990s. This book is based on five stories of five women, and eventually these women converge in a garden in an orchard in the countryside. As an exercise to get started for the feature, I started to shoot two of the short films about two of the women, Mahdokht and Zarrin. In the meanwhile, I continued to write the script. So the new work that I presented was essentially two of the stories of Women Without Men .

Trailer for Women Without Men

Is this an ongoing project?

I’ve just completed the script. I worked with various writers who had experience with script writing. It’s a very complicated book, particularly because it’s surrealistic, and to make such a book into a film is very complicated. But we are very happy with what we have. I’m working with a film producer, and we are now in the midst of fundraising. We have succeeded to raise much of the money from the film world, and we are scheduled to shoot the rest of the stories in January 2007. It’s a period film that takes place in the 1950s, so it requires lots of research and a lot of pre-production, and that’s what I’m busy with right now.

Where will you be shooting?

The film is being shot in Morocco. The stories of Zarrin and Mahdokht were shot in Marrakech, and the rest of the film will be shot in Casablanca because we are trying to recreate Tehran, the capital of Iran, in the 1950s, and Casablanca is a city that still has some resemblance to Tehran in the 1950s.

Could you say a little about the stories?

My attraction to this particular story is multi-layered, partially because the period in which it takes place is during the time that we had the CIA coup d’état that removed our beloved prime minister, Mossadegh, from power and reinstalled the Shah. This is a period that is very important for Iranian political history and the Islamic Revolution that came eventually. It also marks the beginning of the extreme antagonism of Iranians against America and the beginning of the deterioration of our relationship with the West that eventually spread into other Middle Eastern countries. Most importantly, it was the beginning of the exposure and eventually the fragmentation of Iranian society between those who were very attracted to the West to those who wanted to remain within the parameters of their own authentic and traditional society—in particular, Islamic tradition. From this period on, we developed this division of class, and also of ideology, that was pro-West and anti-West.

The story follows the lives of five women, and interestingly the writer chose five women who each came from extremely different social and economic classes. Through following each of the women’s lives, we get a very good picture of the political, social, and cultural situations in Iran at that time. I like this book, and I think what is important to me is the philosophical and poetic aspect of these women, who are each running away, for one reason or another, from their lives, whether it’s sexual or social or for whatever reason, and running away from the city environment to take refuge in the natural environment, in the countryside. They coincidentally come together, removed from all the social illnesses they faced by themselves. Once they’re together it’s really fascinating how they go about coping with their pain and looking for solutions for the future. My fascination with the writer is that she uses references and symbolism that are not just exclusive to the Iranian Islamic tradition but also the Christian—for example, the Garden of Eden. The book is banned in Iran, and she was imprisoned for nearly five years for this book of various reasons, even though the period it’s set in is the 1950s. But she was brave enough to touch on various problematic religious and sexual issues, and this book, to this day, is banned, and she paid a great price for it. For me, aside from all of this, it’s quite a motivation to give life to this very important book.

Shirin Neshat,

Pulse Series

(2001) is available on Artspace

Shirin Neshat,

Pulse Series

(2001) is available on Artspace

Do you feel that this is a kind of reflection of what’s missing in Iran for women at the moment? For you, I suppose, it may be a kind of hopeful view of the future.

Partially why I chose this tale is that, although it’s really, truly relevant to the situation of women in Iran then and now, it’s also very worldly. I think to some degree women across the world have oppressive lives in the sense that men are always in a better state than women are and women are constantly dealing with crises. It varies from degree to degree and from culture to culture, but we’re here dealing with very philosophical questions, and I think that it is in some sense the question of gender. If you are truly given the chance to take time out from society, and you’re faced with yourself, then what?

Do you feel this work should be shown in a cinema, in a museum or in a gallery? Or will it cross over all those types of venues?

Actually, I’m working with a film producer who is not interested in galleries or museums or art theaters, so it is really a great task for me to make a film that is accessible to the mass public. At the same time, while we’re making a very sort of linear film, I’ve conceded with individual video installations based on each character, which could be seen independently at museums and galleries, which are not really narrative but more sort of glimpses into the characters of each one of the protagonists. Perhaps I could do it without works and dialogue and really sort of rely on that visual vocabulary in communicating my concepts. This is the kind of a task that I put in front of myself—that is, create a film that could be seen by the general public in regular theaters but also create individual video installations that are inspired by each of the characters.

Can I just ask you about your situation with your country?

Well, it’s interesting, I have been in touch with some young Iranian artists, and I realize the difference between generations of artists from Iran. It’s no wonder why I have such an obsession with certain themes, such as exile or isolation. There is such an obsession with certain themes, such as exile or isolation. There is such a melancholic feeling in my work because I am truly separated from my country, and politics, in many ways, has defined my life. I haven’t even seen my family—or I’m not able to be reunited with them very easily—because I’m not allowed to go in and they’re not supposed to come out. So however I look at it, it’s a rather tragic and terrible situation that has been imposed on me. Of course, younger artists, new-generation artists who have grown up in the West or who are able to go freely back and forth, have a lighter and less angry, less dark relationship to Iran. I wish I could say that about me, but unfortunately this idea of exile has this shadow over my life, and until that’s resolved I think it will somehow find its way in my work.

Perhaps that’s also the difficulty of being a woman in that society.

Yes, and that’s very interesting, but oddly enough, in cultures such as Iran, where we expect the woman to be less vocal and more hidden, what is an interesting phenomenon in the recent years is seeing this incredible rise of Iranian women as cultural activists. You have Shirin Ebadi, who won the Nobel Peace Prize, and you have many other significant female writers and artists and film makers. So that’s really symbolic of how contrary it is, our image of women from that part of the world where they’re supposed to be very submissive, but in fact they’re incredibly vocal and intelligent, and their voices are just very different from the male voices. But they’re incredibly creative in finding a place for themselves and being outspoken. I fall into that category of women, I suppose.

RELATED ARTICLES:

The Other Art History: The Non-Western Women of Feminist Art