Last year’s Frieze New York was unusually colorful, even by the standards of this dizzying mercantile environment, as visitors paraded down the aisles in capes patched together from brightly hued fabric remnants—wearable art, distributed free of charge by the Frieze Projects artist Pia Camil .

As part of her recent solo exhibition at the New Museum , the Mexico City-based artist (who shows with Blum & Poe in New York and Los Angeles) also encouraged visitors to walk away with some of the art. This time, however, they have to give something in return: an item of personal significance. The idea was to turn the museum’s lobby gallery into both a thriving marketplace, modeled on the famous La Merced in her hometown, and a performance stage that plays up the increasingly transactional nature of the art experience in our selfie-seeking, fair-driven age. “It will be successful as long as it makes people aware of the shopping experience and how naturally it comes to us,” Camil says of her installation, which was titled A Pot for a Latch in homage to the Native American potlatch ceremony, where tribal leaders would give away (or destroy) vast troves of goods as displays of wealth.

This January, while putting the finishing touches on her installation (which was on view through April 17), Camil met with Artspace deputy editor Karen Rosenberg to talk about what artists can learn from social media, why commercial interventions like hers are the new Relational Aesthetics, and what to make of the perpetually “emerging” Mexico City art scene.

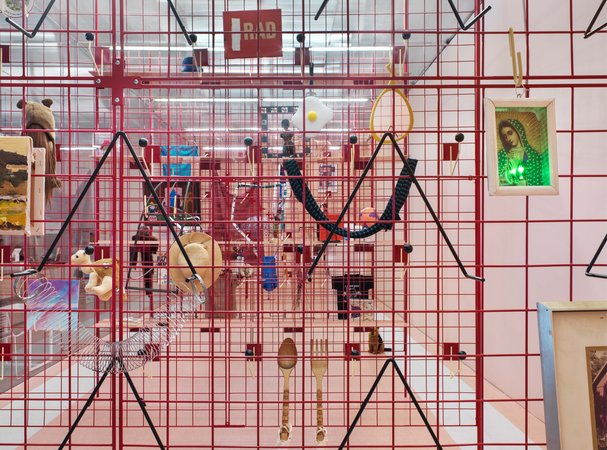

Installation views of "Pia Camil: A Pot for a Latch," 2016, courtesy New Museum, New York. Photos: Maris Hutchinson/EPW Studio

What was the impetus for your New Museum project, A Pot for a Latch ?

It came out of my extensive research on low commerce—markets, dollar stores, and the equivalent to what you would find here in Chinatown or the fashion district. Downtown Mexico City is a highly commercial area, but for low-end commerce. There are a lot of stores that have the same type of display—slat-wall paneling, grid walls. The studio where I was working at the time was right next to one of the biggest markets of Mexico City, La Merced. It spills out into the street and most of it is black market, and they use the same type of layout. It’s really dense—one grid wall after another after another.

When I see something like that, I usually find some art reference that engages me. In the case of the slat walls, I immediately thought of Frank Stella ’s linear paintings. So I did a show of those, adapting and reconfiguring slat paneling into Stellas. And with the grid walls, the reference is Sol LeWitt —I saw a drawing by LeWitt that was pretty much what you see when you’re standing in the entrance of this gallery, a moiré pattern of repeated grids. And then I came across some Agnes Martin drawings I really liked.

You’re talking about this work, and the inspiration for it, in very formal terms. What about the participatory element, the exchange of items with visitors?

After that formal structure was defined, then I started working with other ideas. When I started thinking about exchange, I started to read about early economic systems. The first thing I came across was the potlatch, in Marcel Mauss’s book The Gift . He uses this term, potlatch, to describe Native American economic systems, but also as a general term for any sort of primitive society’s systems of exchange. It was a contract you would establish with a person or group of people— once you gave something, it was implicit that you were expecting something back in return. There was something there that I thought would be really interesting to apply to art and the art market: How could you re-establish contracts with people that weren’t just purely based on economic value?

I did an edition of 100 sweatshirts, which have a text—they’re pretty much like a contract in a sweatshirt. The idea was that I would give those out for free and get 100 objects in return, and then start a system where every so often we would exchange an object on the grid for another object that was brought by a member of the public, and then it’s pretty much up to the public to give the piece its character.

This piece has certain similarities with your

project

from last year’s Frieze New York, in which you distributed colorful capes and ponchos to fairgoers. But at Frieze you were giving away something for free, and not really asking for anything in exchange.

The two projects are totally connected. But the Frieze one was—I always describe it as a little bit perverse on my part, because I wanted to play around with fair dynamics. Art fairs have changed our experience of art, and also the artist’s experience of art-making—artists now produce work around the fair schedule. It’s a little insane in that regard. So I thought, in a place where everything is worth something, I’ll just give out something for free.

There was this piece by Hélio Oiticica that I really liked, that put the spectators at the center of the work by having them wear cape-like paintings he called "parangoles." It’s a very old work, and his context in Brazil in that time was completely different, but I thought it would be quite interesting to play with those dynamics in a fair context where a lot has to do with people-watching and desire. I thought, I’m going to flip the fair on its head and have people own the work and be part of the work.

You could also say, though, that you were actually asking for something—you were asking people to share images on social media, to take part in a performance.

For sure. I wrote in the proposal for the fair that the way I wanted the piece to be distributed was through people’s selfies. So every time I gave a poncho out, I would remind them: #piacamil.

What that did is, that piece is now a document of people’s experience with the work. To this day, there’s still people uploading photos of themselves wearing the ponchos. You see people in cabs, people on the beach—that sense of the piece just living out there, in such a personal way, is something I really liked. So for this project at the New Museum, I made the editioned sweatshirts because that’s another way this piece is going to live on. And people have started uploading photos.

Do you think all artists today have to be conscious of how their work will play out on social media? And is that kind of consciousness liberating or inhibiting?

You don’t necessarily have to tap into it, but some awareness of how things function now does benefit the work no matter how formal it is. We have to be aware that it’s not the same world that we were in 10 years ago. We don’t have this contemplative, Mark Rothko experience of sitting for 20 minutes in front of the painting. Now we have a minute at most, and we don’t even look at it because we turn our backs to it to look at ourselves in the reflection of the iphone. How do you make work that still provokes an experience in the viewer, considering that new nature of art viewing? That’s something I’m more and more aware of.

What is your relationship to the artists of the Relational Aesthetics movement, who are known for giving away objects and emphasizing shared experiences?

We tend to see works like Rirkrit Tiravanija ’s Relational Aesthetics type of work within the framework of art. I think the most successful places to explore now are commerce, shopping, things that have more to do with capitalist strategies. My piece at Frieze was almost like a bargain sale. I had people line up, and you could go and choose your poncho and take it with you. It’s a very simple thing, but it was pretty effective.

The Frieze fair might have been a commercial context, sure, but here you are working within a museum. Isn’t that the framework of art?

At the New Museum I am working with a space, the lobby gallery, that is a little bit like a storefront. The performative aspect of the work lies in this relationship: people that are out here eating their lunch or having their coffee, looking at people shopping in a contained, quarantined environment.

I’ve always said New York is like being in a walk-in store—it’s one single shopping experience. You’re always thinking, “Could I get that? Could I not get that?” When I come here that’s the first thing that jumps out at me, because I live in a very different type of city.

Can you elaborate on some of those differences between New York and Mexico City, and how they affect artists?

Mexico City is just a monster. There’s a saying we have, in Spanish: “It doesn’t have head or feet.” I don’t even know how it functions. 20 million people, and the economic and political situation that we’re in—it just seems like no city could withstand that. But it does, and it’s this kind of big monster that is strangely very easy to appropriate. You don’t know what to expect, but at the same time that allows you to make it whatever you want it to be. And that’s what I really like, because it’s not a city that is given to you in a package like New York, where every post-graduate and graduate kid comes with a very specific set of expectations.

It’s very permissive. You can do anything, basically. That’s not necessarily a good thing—you can do anything because corruption is incredibly bad, and so you can get away with a lot! But, for art-making, it still has what I think most artists look for, which is a sense of really getting into the city and being able to experience things at a very personal level.

I spent a few years away, and when I came back and saw it with different eyes I kind of fell in love with it again. In my last 10 years of production I have been looking at my city as a Mexican, because I was born and raised there, but also with an outsider’s eye—focusing on things that people in Mexico are pretty used to, like the abandoned billboards.

Yes, you did an earlier series about those billboards. What was it about them that caught your eye?

The city landscape is saturated with billboards—once in a while, you see an abandoned one. It’s the failed aspects of the city that are calling out to me. Big corporations put these billboards in the cheapest real estate, which is probably a shack that’s going to fall apart. Sometimes a billboard falls on top of a house, and then it’s just left there—a Coca-Cola ad, on top of a shack. There’s something there that I think is important to highlight. Most of my works are not deep critiques; they just sort of highlight things.

Mexico City has a reputation as a very artist-driven scene, but fairs are an increasingly assertive presence. How have they changed the city's art scene?

When a person from outside goes to Mexico City, they fall in love with it because they like this sense that it’s “happening.” I always laugh about this with older artist friends, who have been through it before. A curator comes along and says, “I love the city, it’s really just happening,” and we’re like, “It’s been happening for 50 years!” The nature of Mexico is, it’s constantly redefining itself. We lack a structure to hold onto, so there’s this sense of spaces opening and shutting, artists coming and going, and it just keeps evolving because there’s no economy or infrastructure to really hold it in place. I could point to two galleries that are successful that have been on the scene for 30 years—but only two.

What has changed is that now we have this constant of the art fair that we never used to have. I think that has helped things, but I almost think that it’s just going to stay in that “happening” place. The fair has improved, and more people do go to Mexico. A friend of mine opened an alternative to the Zona Maco fair, Material Art Fair , and I’m hoping that changes things. But as I said to Brett, the director of the Material fair who’s a good friend of mine: “You made a fair that looks exactly like other fairs.” To make an alternative commercial fair that looks like any other fair, in a place like Mexico City that has incredible variety—I wouldn’t think that’s the way to go. The city offers a lot more.