If there’s one thing that sets education in the U.S. apart from education in other nations, it’s student debt. Particularly for art students with vague graduate degrees that don’t offer much in the way of job security, the cost of tuition has in many cases left students worse off after graduating than they were before becoming a student. Digging oneself out from under tens-of-thousands of dollars in student debt is hard enough, let alone finding the time, energy, and money to be creative at the same time. So, what can be done?

New York’s Bruce High Quality Foundation University proposes a pretty good solution: students take courses ranging from technical, hands-on studio workshops like “Drawing, Drawing, Drawing!” to intellectually rigorous, discussion-based seminars on topics like “Humor and the Abject” and “Image Ecologies”—for free! How is this possible? The school is funded by donations. Now, Kickstarter has partnered with BHQFU to crowd-source funds to start a free printmaking program in Zambia, and Artspace is helping out by producing prints that will be offered as rewards for donating $175 or more to the campaign.

To find out how donations might be put to good use, Artspace’s editor-in-chief Loney Abrams sat down with BHQFU's outreach director Sean J Patrick Carney and studio manager Ana Božičević to discuss an alternative model to the flawed art education system here in the US, and their new partnership with a children's art academy in Zambia.

How was the university started and what is its relationship to the Bruce High Quality art collective?

The collective started the school in 2009, and for a while the school was very separate both in its physical facility and in its mission, in order to quell this idea that the school was just a big art project. It was really quite an earnest attempt to start an educational alternative, and I think that the collective didn’t want it to be perceived as some big art prank or art project. But two years ago, once the school established its own footing, they became more intermingled. We also moved BHQFU from the East Village to Sunset Park where the Bruce High Quality studio is. So now everything happens in the same space, but they are two different organizations legally. BHQ is an art studio for-profit business, and BHQFU is a non-profit operating in the same place but with a very distinct mission. One produces artworks; the other produces public programs and free classes. There’s a lot of gray area where they overlap.

Did people really think that the school was some kind of satirical art project?

I’m sure that was a lot of people’s perception at first. The history of BHQ’s work involved things like trying to get onto the Jeffrey Deitch reality television show with this goofy puppet as the contestant, and re-producing Cats—the musical on Broadway—in Bushwick. Because everything they did was tongue-and cheek, it was kind of like the boy who cried wolf, where they actually wanted to start a school and everyone was like, “Oh, right….” A lot of people thought it was satirical, another ruse or trick. And I think it was satirical in its way, in that it’s a college that offers no degrees and has no attendance guidelines or grades or anything like that. So in the one sense, it is a joke on higher education to ask why education costs $60,000 a year when we can put forty chairs in a classroom and replicate the same thing.

But I think at its heart, making the school was a really sincere gesture and came out of the fact that a lot of the BHQ people had the privilege of going to Cooper Union and not accruing student debt. Not being indebted was why BHQ was even able to start making work right out of school. And that's the goal of BHQFU: to create a situation where artists come together and learn, and then go out into the world without having the burden of debt on top of everything else. It would be unrealistic to suggest that a lot of our students don’t have student debt because many of them went to other schools—but the idea is that they can still participate in that environment without having out to pay a premium.

What percentage of the students already have MFA’s?

I would say that judging just anecdotally on this last week, which was our first week of Spring semester, it’s a pretty small percent. Maybe 20 percent seem to have a terminal degree in fine arts, and maybe about half have an undergraduate degree in the liberal arts, whether that’s writing or studio art or something like that. And then probably another half are just people who are self-taught. It changes every semester depending on the classes being offered. If we offer a class that’s specifically a conversation about critical theory then of course it’s going to attract a bunch of kids who went art school because that’s their language. So we try to make sure that there’s a balance.

Unlike in MFA programs, we have a mix of people from different backgrounds, and we have no idea who will sign up for each class. Some people will have the “International Art English” vernacular or they’ll have read Deleuze, and they’ll come in with this particular tool kit and can talk circles around everyone else. Then there’s somebody else who’s never read those kinds of things. And what ends up happening is that the person who’s brand new to these ideas is very quickly brought into the fold by the rigor of the conversation, and it elevates the way they can articulate themselves. While at the same time, it forces that person who thinks they know it all to reexamine the way they talk and realize that what they’re saying is totally like inside baseball and makes no sense to anyone but themselves and is actually not valuable for that reason—so they’re forced to take a step back and relearn how to explain these ideas that are valuable and important to everybody, but in a way that isn’t grossly exclusive.

If you don’t have a common vocabulary or a shared knowledge base, than you can’t rely on referencing pre-existing thoughts or ideas that come from other people—critics, philosophers, etc. So you end up actually having to think for yourself because you can’t just quote things you've heard or read.

Yeah, I used to joke that when you go through an MFA program you come out with a “mix-tape vocabulary.” You lean on things you’ve read and you can quote something Žižek said, or something from a Julia Kristeva essay, but you haven’t synthesized that information—it’s rote memory. It’s the same reason why the way they teach math isn’t useful to kids because they just memorize everything and then forget it. You can memorize theoretical talking points and angles that somebody has, but if you haven’t synthesized that information and figured out what it means in your day-to-day life, then it's borderline useless.

So what do you talk about in class? Can you tell me about some of your Spring courses?

Post-Fact Studio, which is Andrew Ross’s class, is a really messy class in a really good way. And it’s a class that’s exemplary of how we create curricula. Andrew had been designing it for months until November 8th, when this massive regime change took place and the class took on an entirely different context; it’s very responsive. We announced the classes very shortly after the election and because we don’t have to run everything through a curriculum committee that takes two years, and we don’t have to get them approved by a dean, our classes can radically change in a moment because of something that’s happened. And that’s something that we certainly think is missing in a lot of education contexts.

So, Andrew's class examines artists who are working in fictions or alternate realities, like Walid Raad, and then asks what can we learn from those kinds of aesthetic decisions about the way politics function in the United States. It’s a class that has guests, critiques, conversations, readings—the things you’d expect from a graduate level seminar class, but anybody can take it and it doesn’t matter if you don’t know who any of these artists are. I think it's essentially a bunch of artists trying to come together and have a collective freak-out about what's going on.

Then there’s Jesse Chun, who is a multidisciplinary artist and has lived in Seoul, Hong Kong, Toronto and now she’s here. The class she's teaching is called “ESL: Transcultural Poetics.” It’s basically a discussion- and a critique-based class that looks at the interplay of text and image—something that Jesse’s work also engages with. She also looks at multi-lingual and transcultural narratives, and some of the students are translators who are interested in talking about some of the problems of translation—problems that are not just linguistic, and how we understand our culture, and what “our “culture is. A lot of people there have multi-cultural personal backgrounds. The base of the class is a book: an anthology of essays called Cross Worlds: Transcultural Poetics, edited by Anne Waldman and Laura Wright. In the first class we talked about translating and how it involves all those balls you have to keep up in the air when you’re comparing two cultures side by side to understand the text or artwork from the perspective of one culture. Another thing we talk about is the rise of phobic sentiment—a topic that is extremely pertinent right now and gives people the opportunity to not only probe the limits of their knowledge and cultural sensitivity, but how they express those values creatively as well.

The thing that’s unique about this semester is that it’s the first time that all five of the classes were developed by a group of people working together. It’s like they made an incredible concept album together, where everybody has their 14-minute track.

Are there other schools that you guys look to for inspiration?

We actually just went out to Denver for about a week in January to meet up with a bunch of other alternative schools. It was hosted by Adam Gildar, who runs a gallery called Gildar Gallery, and Cortney Stell, who runs this nomadic museum called Black Cube. We met them in 2011 during this thing called Teach for America, which was a tour around the U.S. in a limo that was painted like a school bus. In Denver we met with SOMA from Mexico City, which is a really cool artist-run program that does charge tuition, but it’s so reasonable that it’s a great model. We met the Mountain School in Los Angeles, which has taken a lot of forms but is basically a two-week intensive that happens once a year—a particular solution for a particular type of audience. There’s also Open School East in London. BHQFU, SOMA, and the Mountain School hung out in Denver for a week, and it was great. We did tons of studio visits with Denver-based artists and went to their openings; we had happy office hours and went to a bar everyday at four; we basically just shot the shit and hung out and drank beers. It was a cool way to figure out what language SOMA uses, (they’re very practical and studio-based), which is different than the language of the Mountain School, which is maybe more philosophical than either SOMA of BHQFU. Bruce uses a funny-radical-lefty-socialist sort of language.

It’s funny because we can draw inspiration from these other schools, but we also have to understand that our operating model is hyper geo-specific and that maybe the only reason that people show up to BHQFU is because it’s impossible to find a space to hang out in New York where you don’t have to spend money. That may not be the case if you work in Kansas City, or if you live somewhere with a backyard and can have friends over whenever you want. But in New York, it’s going to cost ten dollars a minute to exist anywhere. So you fill a room with twenty chairs and people will show up consistently just because it’s a place to hang out and engage in ideas after work without spending any money.

Going to gallery openings is free, but it’s a very different environment.

There’s no where to sit down.

There’s no where to sit down, and it’s so blatantly clear that you’re in a show room too. Galleries are lit to make the work look nice, not to make you feel comfortable. I rarely ever hear people actually talking about art or having meaningful conversations at galleries. It’s so not conducive to the types of conversations you’re fostering at BHQFU.

They’re not designed to stimulate conversation. That’s not to say that there aren’t really interesting artist-run space that do stimulate conversation. And as an organization we’re not anti-gallery. We’re not saying “smash this, rebuild this,” but we are creating a situation where people can realize that when we say the “Art World” with a capital A, we’re referring to a fiction. There are multiple art worlds happening in parallel and it’s perfectly fine if you and your friends who live in Bay Ridge want to start a critique group. That can exist and it is not antithetical to David Zwirner, for example. Yet somehow the art world is generally described as this monolith. We just want to create another space, and it's not designed to get rid of MFA programs, although hopefully we freak them out a bit by being ridiculously left of center and running the worst business model that anyone could possibly do, which is: raise a bunch of money to give art school away for free. (Let’s be honest, that’s dumbest thing because there’s no return on that—it’s a fools errand.)

So how can you have a free art school? What is this stupid model?

It’s fundraising. On our Wikipedia page it says that the space is funded by a mysterious benefactor, that we’re just getting money pumped to us from one person. It’s not true. Seeing how it gets made is actually really boring; we rely on individual giving, constantly, everyday. In a way, that’s very exciting way to operate because your not beholden to a single benefactor or to your board, which means you’re very free and you can kind of do whatever you want. But it's also very intense because we’re constantly raising money to keep the doors open, to keep it going another year. There’s a level of precarity that reflects the lives of the students. And that precarity gives us a sense of urgency; not knowing if we’re going to be here in two years causes us to work really hard.

You’re current Kickstarter campaign is one of the many forms of fundraising that you’re doing. Can you tell me about the campaign?

We’re partnering with a New York-based non-profit called 14+ Foundation, which is a group of people from Zambia and the United States who essentially produce infrastructure to build small economies and schools in rural parts of Africa. The anti-neoliberal in me has a knee-jerk reaction like, “What are you really doing?” But we’ve been working with them for a while, and they actually, literally go to a town and give micro loans to women in the community who then have functioning businesses, and then they build roads and they builds schools. How it actually started was that there was a drive to get bikes to kids so that they could get to their school that was seven miles away. And then they started thinking, “Why don’t we just build them a school?” That seemed like a much better solution than formalizing the kids' endless and brutal commute to school.

Now we’ve partnered with them to work on the Chipakata Children’s Academy which was finished in 2015 and has about 200 kids in grades one through six. Originally we were going to do a mural but we were very worried about parachuting into a place and being like, “Here’s a thing! Boom!”—and then disappearing. So through conversations with 14+ and the school, we came up with this idea to build a printmaking program. And so the Kickstarter campaign is to raise money so we can set up a press that will give students the means to continuously produce multiples and to experiment. The project is the beginning of a long-term partnership between us and them, which will eventually involve us setting up a teaching residency there. So it’s not simply this one-off campaign; it’s putting this idea out there that free education is a right and not a privilege.

Students in class at the Chipakata Children's Academy

Students in class at the Chipakata Children's Academy

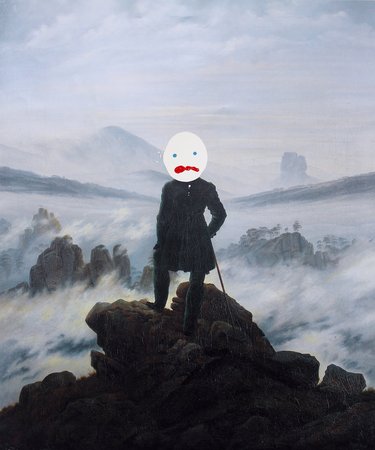

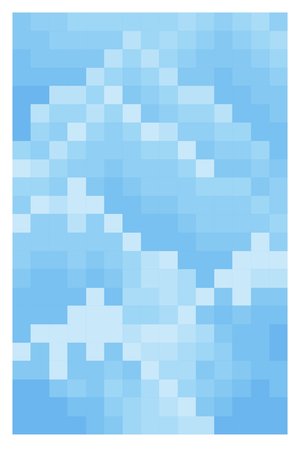

Can you tell me about the editioned print that Artspace is producing for the campaign?

Artspace is producing two different prints that are going to be rewards for the Kickstarter campaign. One is about 12 by 18 inches and there are four different color treatments of it. It’s basically a pixel-y mosaic image of some mountains. We asked Rashid Johnson (who is one of the artists involved with 14+) to describe How To Move a Mountain, which is the title of the project. He said, “You can’t move a mountain by yourself, but you can get people in your community to move it piece by piece, and then all of a sudden, this giant thing that you didn’t think you could move isn’t so giant after all.” So that’s how that image came about.

The other print is a bit fancier and larger. It’s 20 x 24 inches and it’s called The Wanderer. It’s a classic painting by Caspar David Friedrich that’s been “Bruced.” In other words, it’s a very trope-y painting (nothing against the painter) with a “wanderer” looking out over the landscape. But the wanderer has a goofy dumb grin, and his head is turned around Exorcist-style, as if he’s smiling back to the camera for a photo op. It has reverence and a little bit of a distrust of art history. People sometimes use word “satire” interchangeably with “ironic” but actual satire comes from a place of serious interest and care. It’s not just making fun of this or that—it’s hopefully starting a conversation.