What would you do if a stranger sent you a video of herself, playing soccer with a dead chicken? In the case of erstwhile Museum of Modern Art curator Barbara London, she had to consider whether the tape was worthy of a place in MoMA’s permanent collection.

Between 1973 and 2013 London worked at this esteemed New York fine art institution, helping MoMA establish itself a preeminent position in the field of video art. Her new book, Video/Art: The First Fifty Years , describes the development of this new medium, its key practitioners, and London’s role in documenting and developing the form. In this interview, she runs us through her early studio visits, the schisms that arose in the scene, and how, nearly half-a-century on from her entry into the art world, she’s working hard to understand what’s coming next. (And, because these things are important, you'll also find out which artist sent her the chicken video).

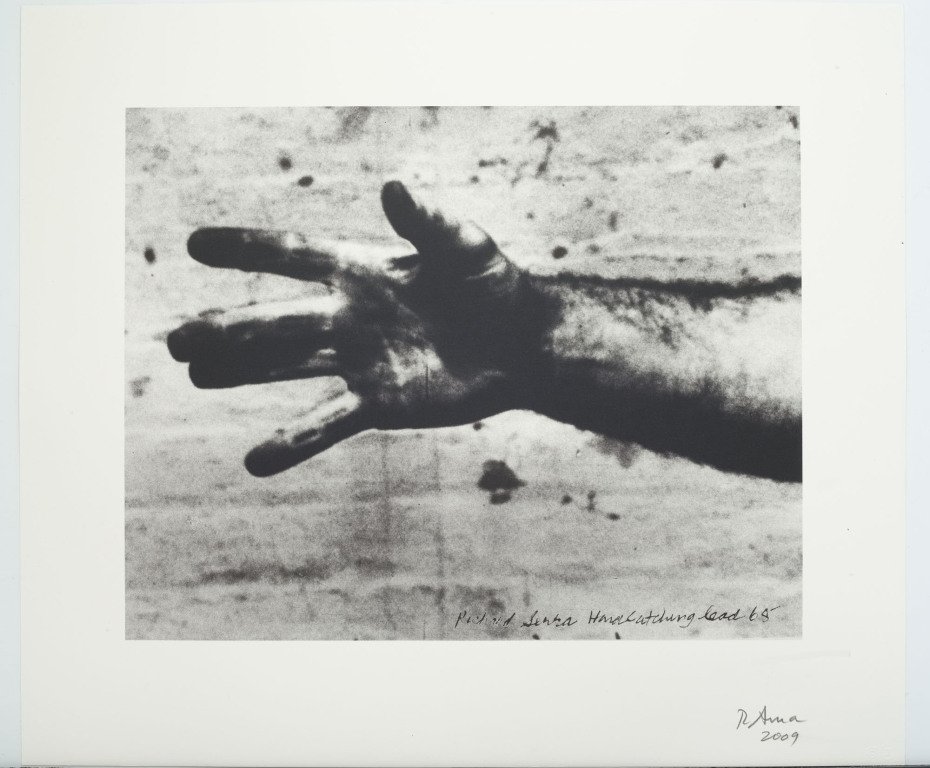

Still from 'Hand Catching Lead' 2009 by Richard Serra

When did you first come across artists using videos?

In the early 1970s when I began working at MoMA, I was based in the International Program, a department that oversaw exhibitions that MoMA circulated abroad. I worked with an important mentor, the contemporary curator Jennifer Licht, on a sculpture exhibition entitled "Some Recent American Art," which was headed to Australia in 1973. Together we selected a relevant video art component for the exhibition. That’s where I came across works by Vito Acconci , Lynda Benglis , and Richard Serra . That was my start with video.

Though your book is a history of video art, there’s a little bit of prologue, where you describe artists such as Merce Cunningham and the Velvet Underground. Why do you include those guys?

Because something new does not emerge out of nowhere, there are roots and connections. Many of the young, first video artists had mentors. Bill Viola had David Tudor, and Nam June Paik had people like John Cage . Artistic influences weren’t restricted to the art world. Interdisciplinary artists tended to hang out in the same clubs, alternative spaces, and bars. Artists, dancers, and musicians usually frequent each other’s events. That’s true for New York, Paris, London or Tokyo – that was of interest to me.

Eric Emerson (Chelsea Girls)

1982 by Andy Warhol

Eric Emerson (Chelsea Girls)

1982 by Andy Warhol

Warhol also seems to loom large in this early history too.

For artists in New York, Warhol was certainly a figure. A little older than the first video artists, Warhol experimented with a range of mediums including film, and was definitely around on the scene. Also, the first artists who picked up consumer video cameras were looking at the mass media, but wanting to do something different and individual with it. That relates back to Warhol.

In your book, you describe an early schism between filmmakers, working in celluloid, and early video artists. How did that come about?

Well, there are always different camps of people. Sometimes I get annoyed when people talk about the Downtown art scene being one group. It wasn’t, there were multiple factions. With gear being so new, artists shared technical information, but tended to be competitive, especially about funding. This initially was true about those working in film, and those who were working in video. In the early phase when they were a bit competitive, such new organizations as the National Endowment for the Arts and the New York State Council for the Arts started to offer funding to artists. I think the film people thought, “Oh, they [the new video artists] are going to receive all the grant money.” That was one thing. But filmmakers were also protecting their own turf. They thought you couldn’t edit with early consumer video, or if you could, it was very crude. With early video, the depth of field was limited too, and the image was grainy. Yet you could do other things that were great about video.

For example, you could turn a video camera on and you could see the live image straight away on your monitor screen. You could hit your record button or not; you could perform with a live image, or you could run a pre-recorded tape as you performed. There was malleability in a way that had to do with the “now”, the present.

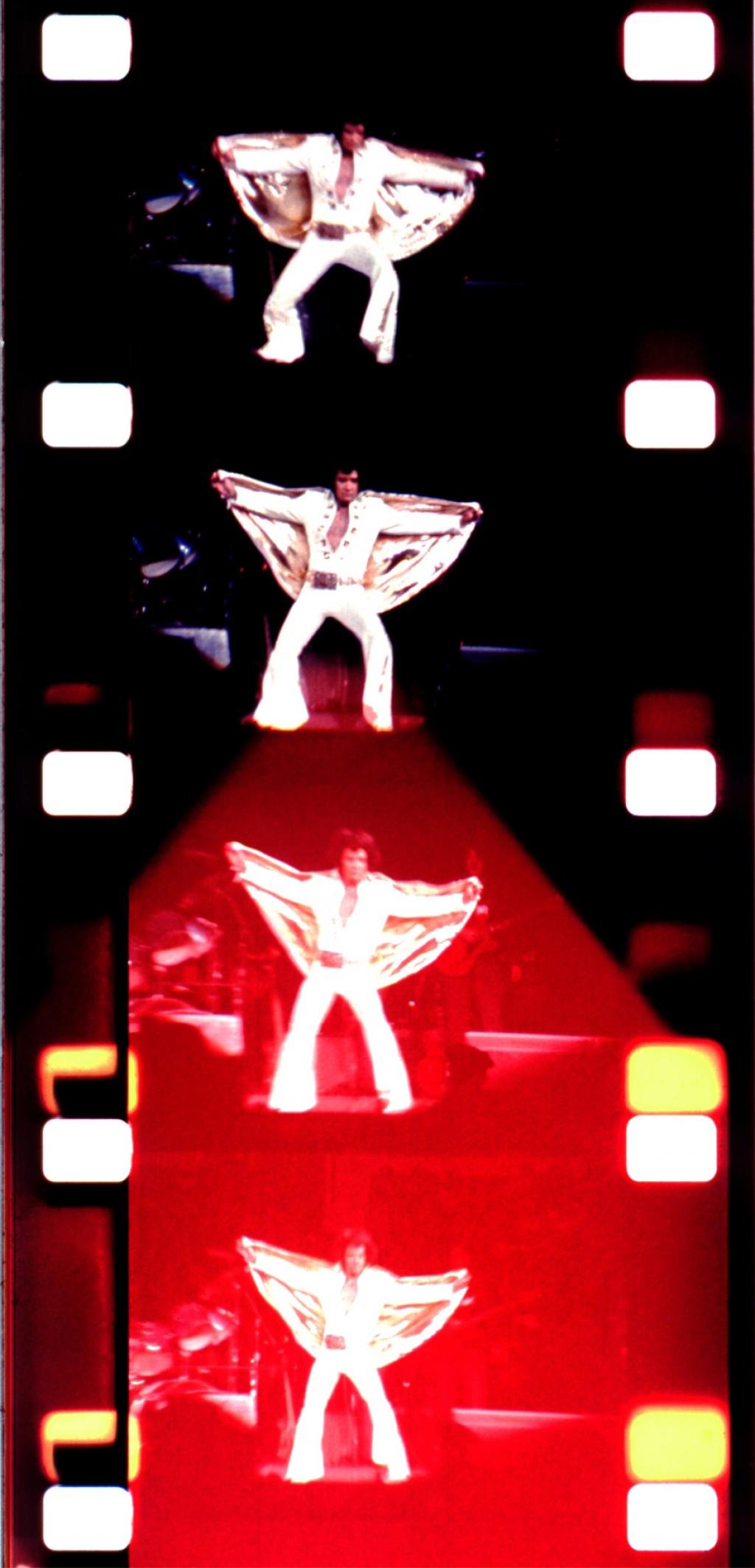

Elvis Presley, Madison Square Garden, New York, June 9, 1972. Last New York Concert

, 2010, by Jonas Mekas

Elvis Presley, Madison Square Garden, New York, June 9, 1972. Last New York Concert

, 2010, by Jonas Mekas

Was it easier to present video works as art at MoMA, ahead of other intuitions, as they already had a film archive?

Yes. MoMA had a very extensive film collection, which included the early work of D. W. Griffith, and early Hollywood masters, but it included more experimental works in in the collection too, such as films by Shirley Clarke, Jonas Mekas , and John Cassavetes. This was an important context for video.

I was offered a curatorial position in the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books, and from there started to develop the fledgling video program. The administration observed what I was doing and thought, “Oh here’s this young curator pursuing video as art, let’s encourage her.” I jumped at the opportunity.

Was it easy to get video art taken seriously? Who encouraged its development?

There were people like Bill Ruben, who was a very powerful figure at MoMA and a great Picasso scholar, among other things. He was happy that I was not in his department, which meant his staff didn’t have to devote time to video. Meanwhile, a number of painters and sculptors, as well as musicians were picking up on video. I tried to have everyone at MoMA know what I was doing, and be aware of the curatorial decisions I was making. Meanwhile I tried to see most contemporary shows, and attend openings. If an artist came into town from, say, Europe, if they gave me a call, or wrote me a letter I always met with them; they shared important new information. I wanted to find out what they were doing.

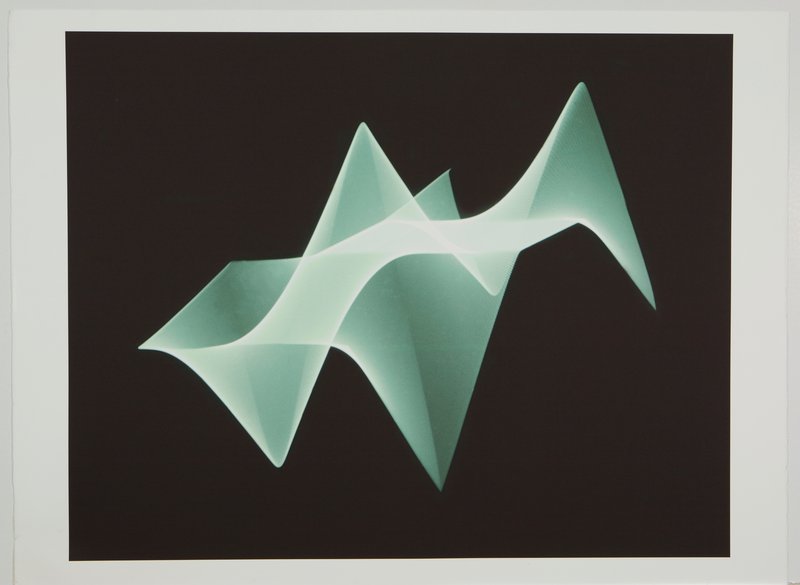

Waveform Studies XXI,

1977-2003 by Woody Vasulka

Waveform Studies XXI,

1977-2003 by Woody Vasulka

You were sent quite a few unsolicited tapes at MoMA. What ones stick in the mind and did you come across any future classics?

Artists like the then California-based artist Nina Sobell came across my radar that way. She made a surprising, early verité videotape in which she performed with a raw broiler chicken that she bounced on her foot.

Could you tell us about the Castelli-Sonnabend Tapes and Films - the video library set up by two of the world’s most famous gallerists?

Yes. The gallerists Leo Castelli and Ileana Sonnabend had been life partners and remained good friends, with galleries one floor above the other in early Soho. They recognized that many of their artists were experimenting with film and video, and it made sense to them to augment and be inclusive about their artists’ output. They hired someone specifically to oversee a sort of library of unlimited edition work to rent or sell to libraries, schools, and museums, and make it a success. Prices ranged from say $50 to rent for a single screening, to $300 for the purchase of work by such prominent artists as Richard Serra .

There were similar undertakings, such as the non-profit Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), a postproduction and distribution facility set up by the gallerist Howard Wise. Castelli-Sonnabend Tapes and Films closed down after 10-15 years, but EAI is still going strong.

Telephone X

, 2000 by Nam June Paik

Telephone X

, 2000 by Nam June Paik

You write about visiting Nam June Paik in his studio, and finding him surrounded by wires, and wearing rubber boots to prevent electric shocks. Were all early video pioneers tinkerers or technically gifted?

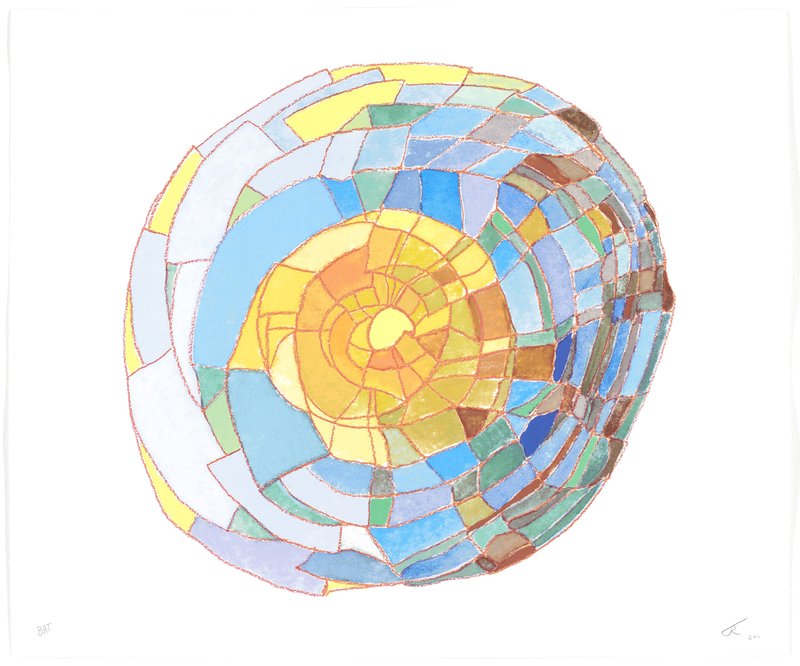

I would say many were tinkerers who started out at ground level. Whether they were Steina and Woody Vasulka , Joan Jonas , Gary Hill, Bill Viola , they really went to the nitty gritty of the electronic signal. They understood that sound was of equal importance to the image. They tried hard to figure out editing; and they were interested in time, and how editing in video affected the viewer.

Then again, technical skills today are really important. Even if you’re using off-the-shelf software, you need to be really engaged; you don’t exactly have to hack your software, but you really need to understand what it can do; and there’s craft in there.

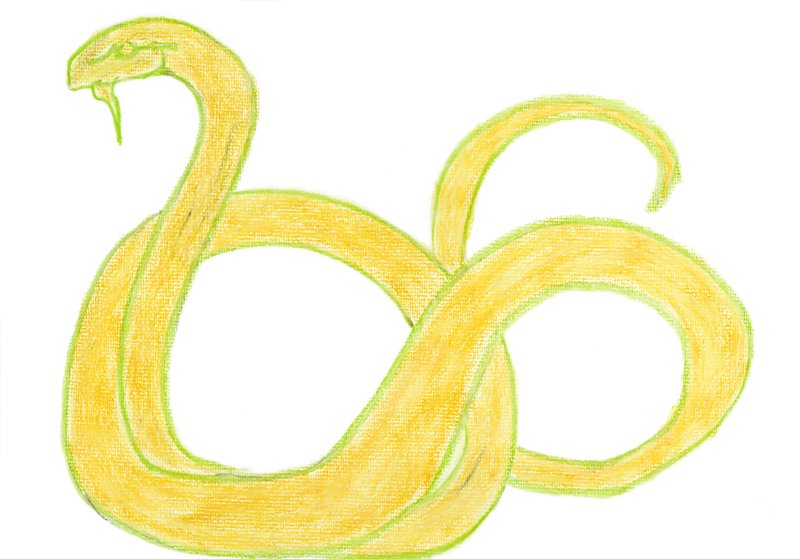

Coil Snake

, 2017, by Joan Jonas

Coil Snake

, 2017, by Joan Jonas

Which other studio visits really stand out?

I went to China in 1997 to research media art there, which I was starting to hear about. A few artists had mobile phones but no one had internet. I made my way to the minuscule home that interdisciplinary artists Song Dong and Yin Xiuzhen shared. This was my first exposure to traditional courtyard residences, with many families living in close quarters, known as hutongs. I saw how artists like them were talented and innovative. I had to work very hard to understand their background and perspective. I was the one who had to grow and expand my perspective.

Music and performance seem to shape early video art. Could you tell us how they shaped the form?

Today we might think of “promotional” music videos as a commercial invention, but, the way you tell it, musicians pioneered the form? In the late 1970s/early 1980s I met The Residents, and Captain Beefheart, and at the same time I admired David Bowie’s video works. These were very unusual creative people, who really understood what the technology could do, as well as what rights issues are. From the get-go, The Residents controlled all rights to their work, so always could appropriate their own material, rework it, and transform it into something else. That’s a group really on top of their game.

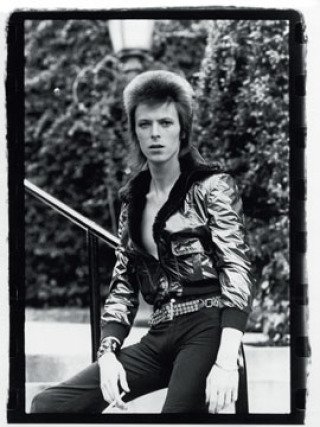

David Bowie was interesting and very astute, too. From the beginning, say starting with the music video for his early song Space Oddity, he had clear aesthetic ideas about what he wanted. He hired very talented people like the photographer Mick Rock to work with him. You’d never hear him use the word collaboration, because the aesthetics were 100% Bowie.

David Bowie - Beverly Hills, Los Angeles

, 1973 by Mick Rock

David Bowie - Beverly Hills, Los Angeles

, 1973 by Mick Rock

Your book is a wonderful first-hand account of the New York art scene in the latter half of the 20th century. It all sounds so open and collaborative. How did this social milieu help the development of video art?

Very early on, artists shared technical information, because there were no how-to manuals. People who worked on documentaries would share how-to knowledge with the “fine artists” and exchange ideas. There was an important early magazine founded by artists called Radical Software, which offered a lot of technical information. And there was a group out in Vancouver called Video Satellite Exchange, which worked very hard to share both technical and conceptual information with artists all around the globe.

At one point in the book you write about how early tapes weren’t the most stable media, and that they often became unreadable after a few years. Are there any lost classic works you wish you had seen?

Yes, here is one example. The group Ant Farm had all their masters and sub masters stored in offices that went in flames. They had to scrounge to find out who might have had decent copies of their work. A lot was lost.

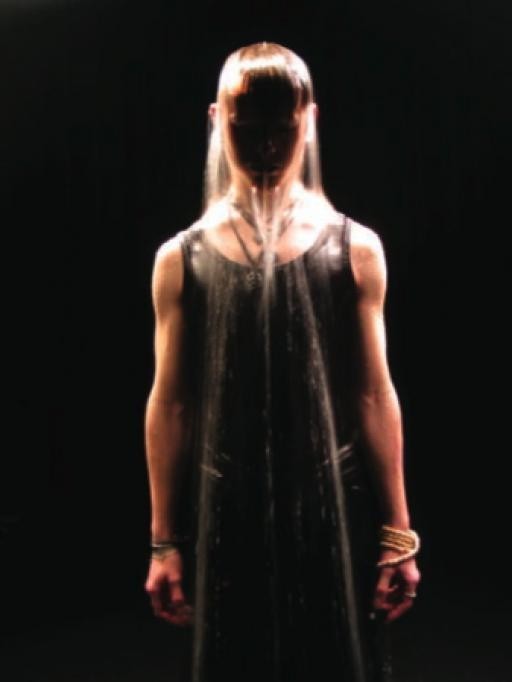

Ocean Without a Shore,

2007, by Bill Viola

Ocean Without a Shore,

2007, by Bill Viola

How important is old tech when it comes to showing older pieces. Can you show Nam June Paik on a flat screen? Or a Warhol Screen Test on a digital projector?

This is very complicated! Sadly, if an artist passes and didn’t leave clear definitions about the aesthetics of their work or instructions for displaying, this becomes a problematic situation. For example, if a museum or a private collector owns a work but didn’t obtain clear instructions at the time of acquisition, then who can make those important decisions about upgrading display technology if the artist is no longer here? Consider the 1990 work by Gary Hill, Inasmuch as It Is Always Already Taking Place, which entered MoMA’s collection. It has 16 TV tubes that have been taken out of their console. You’ve got the 16 TV tubes and the elongated wires going from each tube to its chassis. It’s a technically complex and fragile work. Fortunately, the Museum has diagrams, and a technical staff that has installed the work several times. Staff from curatorial, conservation and registrar departments have formed a brain trust about the work.

When a museum or collector acquires a work, it is incumbent on them to conduct an interview with the artist to find out what are the key aspects of the aesthetics. If the TV tubes no longer exist, does the piece die? In the case of Gary’s piece, I think MoMA obtained three back-up sets of TV tubes, so at least it would have a life into the future.

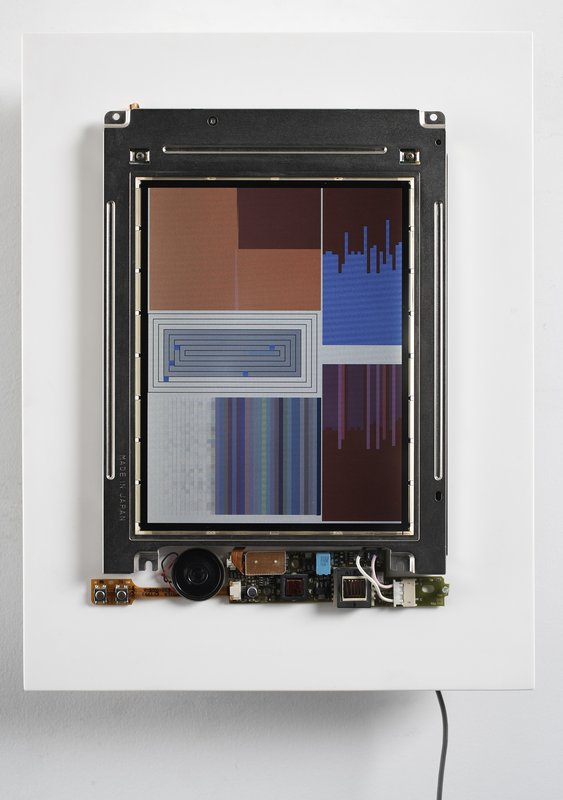

Color Panel v1.0 1999, by John F. Simon, Jr

Color Panel v1.0 1999, by John F. Simon, Jr

So, places like MoMA and the Tate have art conservators with skills akin to old school TV repairmen?

They do now! In the mid-1970s, when we started to acquire video art work, there were two projectionists and me who learned on the job. An engineer from CBS, the TV station across the street, taught us to clean our tape-deck heads so the cassette player wouldn’t gunk up.

Then in the 1980s, the projectionists became savvier, as did MoMA’s exhibition staff who install art works, and they became more technically skilled. Then you move up another decade, you’re into the digital age, and you need staff with the knowledge of a TV repairman, but also the knowledge of a software engineer.

For example, when the Museum acquired a work by the artist John F. Simon, Jr. I also obtained details about the software code he wrote for his piece. Initially he was a little reluctant. Some media artists earn a living developing software for others. But the museum or private collector needs these details, because, in the future, the artist may no longer be around to instruct about the inevitable upgrade.

Something else I learned is that there’s an art to conducting interviews with artists when an institution acquires artwork. It’s very important to gather information, because in the future you’re going to need to know what the artist had in mind in terms of aesthetics. In fact, those interviews will help subsequent generations of curators and conservators make important decisions. Today’s digital art curators and registrars might look back at, say, a Corey Arcangel interview, and choose to make certain decisions based on the interview made with him at the time of the acquisition.

Some successful video artists, such as Miranda July and Steve McQueen, have gone on to find success in the film business. Does cinema pick the best artists? Should a good video artist make it in film?

I don’t know. Those are very particular people. I think Steve McQueen, for example, is a genius. I worked with him on installing his installation Deadpan at MoMA. I knew he was a great artist, but I had no idea he would blossom and create these major, award-winning cinematic works. He evolved and was ready to tackle the industry.

The Secret Agent, 2015, by Stan Douglas

Looking back over the last 50 years, what stands out for you personally?

Well, since the start of my career I’ve been fascinated by the “new.” In the early 1970s, I tried to figure out what was going on with inexpensive artists’ books, a dynamic form that felt fresh and new. For MoMA, I assembled a collection of artists’ books and organized the BOOKWORKS exhibition, and then moved on to video. As technology has changed and advanced, I’m interested in new media, whether that’s VR or augmented reality. When I teach graduate art students, I start by explaining that I’m of a different generation. I understand the codes of the culture I grew up with the best, and I want to learn as much as possible from my students what their codes are. It always takes some time for me to understand the very newest work. I have to ask a lot of questions of younger artists. It may take me a little longer to glean, but I certainly will keep trying.

To learn more about the definitive days of video art, and Barbara’s role within its development, buy a copy of Video/Art: The First Fifty Years . In this book, she traces the history of video art as it transformed into the broader field of media art - from analog to digital, small TV monitors to wall-scale projections, and clunky hardware to user-friendly software. In doing so, she reveals how video evolved from fringe status to be seen as one of the foremost art forms of today.