You've almost certainly seen the work of Ethiopian-born, Los Angeles-based artist Awol Erizku —even if you didn't know it. The artist staged and shot the now-famous photograph that Beyonce used to announce her pregnancy on Instagram. You know the one—an almost-nude Queen B kneeling in front of a colorful backdrop of flowers donning a long green veil. But while Erizku may be most known for his celeb status (he was dubbed "the art world's new it boy" by Vulture Magazine), his artworks resonate far beyond our handheld screens. For his first solo show (at New York's Hasted-Kraeutler gallery), the artist reimagined Johannes Vermeer's "Girl With A Pearl Earring" painting; only in Erizku's version, titled "Girl With A Bamboo Earring," the subject is a black woman wearing a gold hoop earing. Remixing art history with references to pop and black culture, Erizku takes a novel approach to not only his studio practice, but his exhibition tactics as well. For each solo show that he has, Erizku makes a "conceptual mixtape" specifically for the exhibition, which he plays in the gallery during the opening and gallery hours.

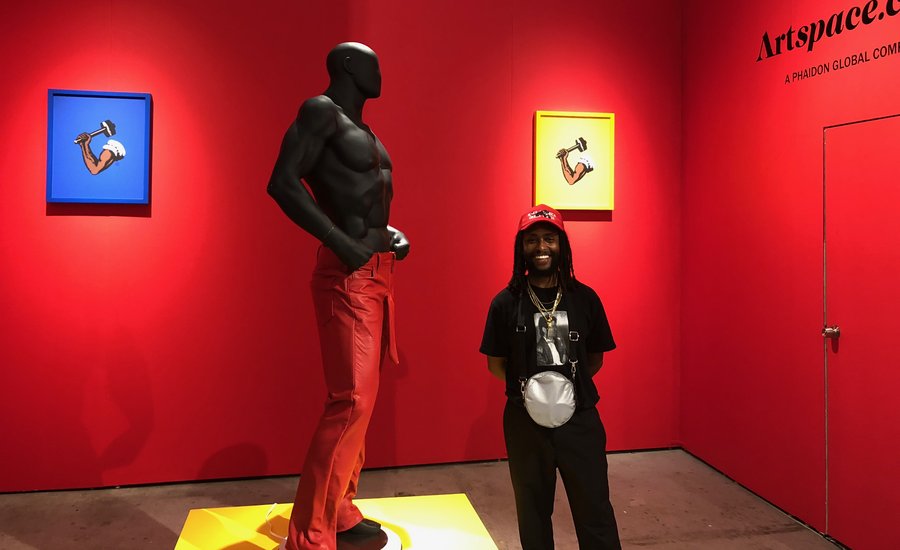

Eruzki partnered up with Artspace last month to produce a limited edition silk screen print , which Artspace debuted at NADA Miami. (Proceeds from the sale of the print will benefit NADA.) Artspace's editor-in-chief Loney Abrams caught up with Erizku in Miami to discuss his work, his approach, and his Artspace edition.

For Hammer, Stick, Same Thang , the edition you made with Artspace, you appropriated the Arm and Hammer logo. What interests you about this image?

I've always thought of the logo as this very hyper-masculine iconography. To me it's very American. After incorporating the nail salon feminine hand ( Fire and Desire , 2017), I was trying to find a male equivalent of that image. I've also been thinking a lot about Warhol and Basquiat 's collaborative paintings over the past couple of years, and the Arm and Hammer logo keeps standing out. The hammer also appears as a recurring theme in my films and still lives.

Hammer, Stick, Same Thang

(2017) is available on Artspace for $1,000 or as low as $88/month

Hammer, Stick, Same Thang

(2017) is available on Artspace for $1,000 or as low as $88/month

In Night Gallery's write-up about the show, there is a quote that reads "the Arm and Hammer image is both localized and ubiquitous and appears across the country in interchangeable locals, signifying a variety of ethnicities and communities." How does the Arm and Hammer logo relate to urban environments, ethnicities, and communities?

It's an iconic logo that's used a lot in music culture — for instance it's used in the music video for rapper O.T. Genasis's song CoCo as this metaphor for "whippin' up the crack" — and that reference has become a part of the drug culture. A lot of my work extracts from contemporary music where "hammer" is used as a metaphor for a gun. What interests me most is how multi-faceted the image is — there are all these layers to its symbolism.

There's one connotation that represents drugs and dirty money, and another that represents cleansing, purity, and sterilization .

Right, it depends on which household it's at. I'm always interested in subverting accepted ideas about what something means, so that you're looking at it through a different lens, or based on its unintended use. To make it a black arm charges the image, because you know the image, but you've never seen it like that.

A strong male arm holding a hammer could either signify a hard-working man, or a violent man. Do stereotypes about Black American men come into play here?

Well hopefully not, but we'll see what people have to say about it. I've shown it in London as part of a triptych called Pull Up Wit Ah Stick, which is the title of a song that isn't necessarily about violence but it does allude to it. I listen to music and think of it in its visual representation — like how it exists in video form. The artist that I appropriated the title from is this young kid from Atlanta [SahBabii]. The video [for Pull Up Wit Ah Stick ] is bunch of kids from his neighborhood, and they all have guns. So that's why the piece is called A Hammer, a Stick, Same Thang . A hammer refers to a gun, and a stick also refers to a gun. There's a lot of wordplay and context being pulled into it but it's also very esoteric. People are either going to see it and say "oh, it's a black arm" or they read the title and put it all together.

So it's either a tool or a weapon.

Exactly, all the keys are there to bring it together. It will be interesting to see what people will say. The Eldridge Cleaver pants also in the installation [in Artspace's booth at NADA Miami], designed by one of the founding members of the Black Panther Party, play into that as well — symbolizing the hyper-masculine. I'm bringing these elements to the surface in this context to explore new ideas.

Available on Artspace for $1,000

Available on Artspace for $1,000

You mentioned Josef Albers being an influence. Can you talk about how he's made you think differently about your work?

I did my BFA at Cooper Union, and a lot of the teachings there extend from the Bauhaus. Our foundation year was all about Josef Albers. It was there that I started to pay attention more and more to the way I used my colors. It's hard not to embrace the masters. When I do installations now, color-play is as important as the works themselves ; I don't do any shows that are just a white-walled spaces anymore. I like using color as a way to bring context, and also as a way to charge space. It's not even for the sake of setting it apart, but just to allow it to exist in a different place.

You also charge your exhibition spaces with music. Can you tell me about the soundtracks you make for each of your shows?

The music that's often played in my studio is what ultimately ends up inspiring a title for a piece, or an idea for a piece. The soundtracks are conceptual mixes that I make for every exhibition that I do, and that's just part of my practice. I'll be making a painting or sculpture or still-life, and then I'll make a mix in the time in-between. There's no separation between these practices, it's all one process for me. The galleries play the mixes for the duration of the show, anywhere from four weeks to three months. The conceptual mixes are my hypothesis for the exhibition. It's not just songs — it's also a lot of soundbites, and clips from Youtube or Instagram. These soundbites help to tell a story, so the mix is not just a playlist.

Most gallery openings are dead silent. Do think the music make your work more approachable somehow?

Absolutely. That's my biggest goal — to make this idea of blackness as accessible as possible without it having this ulterior outlook. Trap music has become the most dominant sound in America right now. I try to embrace it as opposed to run away from it. I'm interested to see how younger kids will use music in the future in relation to the gallery space, this 'white cube' space. I think if you ask me that question in three to five years ... in fact, I don't even think you'll be asking me that question in three to five years, because I think it's going to get picked up by a lot of younger artists and will become a norm.