A lifelong dancer turned performance artist, Brittany Bailey has worked with Merce Cunningham and Michael Clark , re-performed Marina Abramovic 's classic pieces as part of her 2010 MoMA retrospective, worked with Bucksbaum Award -winner Sarah Michelson , and lived with the Whirling Dervishes in Turkey. She has also honed a particularly sculptural approach to dance, creating durational pieces that can last for an hour and a half, as was the case with a finely etched performance she did as part of the Watermill Center ' s July gala as the culmination of a residency at theater impresario Robert Wilson 's foundation. That residency also yielded Bailey's new Book of Shapes , a catalogue of the more than 25 shapes she creates with her body during her performance as a way of articulating and defining space.

Currently working on a project with the artist Christopher Knowles , Bailey also recently published a limited-edition book titled The Dance Warm Up with her frequent collaborator Bryce Hackford (it's available at McNally Jackson in New York). What follows is a meditation on her process and how she built her career, as told to Artspace 's Christiana Tisches .

****

Brittany Bailey performing at the Watermill Center Gala (Photos by Lovis Ostenrik, except where otherwise cited)

Brittany Bailey performing at the Watermill Center Gala (Photos by Lovis Ostenrik, except where otherwise cited)

I first became involved with the Watermill center when an ex-boyfriend and I applied for a residency that we did not receive. A year later I applied again, and this time I received a residency for this past March and April. Marina Abramovic and I have stayed in touch over the years and I had told her I was applying. I think she shared her opinion about me, which I imagine made a difference.

My residency consisted of waking up and going into the studio first thing in the morning and rolling on the floor. From there I would either stay or leave to make coffee. Next I would drink a lot of water, digest, and then go back to the studio to meditate on an empty stomach. My meditation started at being 20 minutes long and by the second week I was sitting for one hour. From there I would stretch my hands and feet, and then work my way into my core; sometimes I would start closer in and work my way out to the extremities.

Next I practiced my technique, a mixture of ballet and Merce Cunningham exercises, primarily stationary. Then I would dance in the full space. At this point I would go for as long as I could. Normally I was quite hungry at this point, or I would begin to want "things," so I would then work with the sensation of being empty for some time and see what "things" I wanted: food, more flexibility, stillness, to move on the diagonal, to jump, or to have all my limbs on the ground.

This part of my routine usually lasted 30 minutes to an hour and I would try not to tap out of the space or the dance during this time. There was almost always a moment where I would realize, "Ok, this dance is done now, you can leave the room." When the moment clicked that it is time to leave the room and eat something, I would. The whole process usually lasted three to three and a half hours as long as everyone left me alone, which they do at Watermill.

After I had worked out the technique portion of my routine, I began videotaping everything . I'm my own teacher, and I typically don't think about anything when I'm dancing, so the video allows me to think about what was happening in the room after the fact. So, after I ate, I would sit down and study the videos and note whatever part needed strengthening technically—perhaps my hands were too stiff, or my neck was out of alignment. Sometimes the adjustments could be done by altering my attention and breath, not necessarily requiring a stretch or exercise. I also noted from the videos if I was leaning towards certain shapes, rhythms, or floor patterns that day, and I would then make decisions about how I would handle them when I returned to the studio.

Before the day was over, Bryce Hackford—the composer that I collaborate with—and I would return to the studio and jam for a while. We never "set" pieces. We worked with a lot of improvisation, and tried to develop a sense of time together. We both created "samples" of sounds and shapes and used these in our improvisations. Bryce sometimes accompanied me when I was working on my routine, too. He and I would usually touch base in the mornings when I was hydrating, and if it seemed appropriate for Bryce to join he would come into the studio about two hours into my routine and begin playing single sounds that lasted for several minutes or more. He's very sensitive and could tell if I wanted to be alone in the studio that day, and even if Bryce came into the studio we did not necessarily talk until later that day. Every day was a little different.

*****

Bailey performing

Bailey performing

I wanted to make a dance that had only one shape in it. I knew there would be movement within that shape, because I would have to breathe and this causes movements, and to me that is a beautiful dance. That is where I started.

What is the best shape? Is it round or square, high in the sky or low to the ground, vertical or horizontal, lumpy or rigid? These are questions I thought about a lot. I knew my tendency and my body's preference: round shapes close to the Earth, with my entire body working as low as possible, and some negative space carved out near the guts or pelvis. I wanted a dance that was about shapes in space, preferably lasting long enough for the viewer to have the time and space to reflect. During the performance, my dance—along with Bryce Hackford's music—was an attempt to expand time and the space.

I am very attracted to high contrast and tried to create that in my studies; my pale skin against a black background, or me wearing a black shirt and curving my spine and making an egg shape against a white background, for example.

I made lots of shapes every day and then studied them.

****

Bailey uses her body to make shapes.

Bailey uses her body to make shapes.

I am 24 years old and have been dancing for 22 years. I began dancing when I was two and a half at a local studio in Hickory, North Carolina. My sister is a year older than me and I would watch her and wanted to do it too, so my parents let me start as soon as possible—this is what I've been told. I imagine I must have always been serious about dancing, since I never took a break from it. Even when all my friends started cheerleading in middle school and were making out with the football boys—and I really wanted to be a part of that—dance was more fulfilling. This devotion had little to do with my parents, except that they supported me unconditionally, paid the tuition, and drove me. I wanted to be there.

A shift occurred before high school: I wanted to dance more, so I switched studios and started commuting three hours a days to a studio in a larger city. This must have been quite difficult on my parents' marriage and probably my sister too, but looking back I think things were always difficult for their marriage. I was so focused on dance that I hardly thought much of it.

My mom and I would get home around midnight, and I would go to school the next day at 7:30 a.m.—or not go to school. My mom didn't make me go as long as I had all As, and I did. After three years of this I was accepted to the North Carolina School of the Arts (now University of North Carolina School of the Arts), so I moved to live in their dorms for the rest of my high-school days. I told myself, "Audition for the ballet department, and if you get in and can get through a year of that, then you can do anything." I have always been a very happy and healthy dancer, which is a very good thing because the school can easily break you in half. After ballet I switched to the modern dance department and met [former Merce Cunningham Studio dancer] Brenda Daniels, who introduced me to the world of Merce Cunningham. Now I was home.

After high school I moved to New York City and trained with Merce Cunningham. Luckily I was on full scholarship, because I had no money and no one in my family could have supported me, so if I wanted to stay in New York I had to find ways to make it work. I got a restaurant job at the Museum of Modern Art and continued working in restaurants off and on during my six years in the city. One day at the Cunningham studio I noticed a sign saying that a performance artist, Marina Abramovic, was looking for re-performers for her retrospective at MoMA, so I called to ask about the posting and they told me to come in and meet with Marina. I didn't know who she was, but we got along and she hired me for the show. This was a year in advance of her 2010 retrospective, so that kept me planted in New York and allowed me to study with Merce Cunningham for the last year of his life.

*****

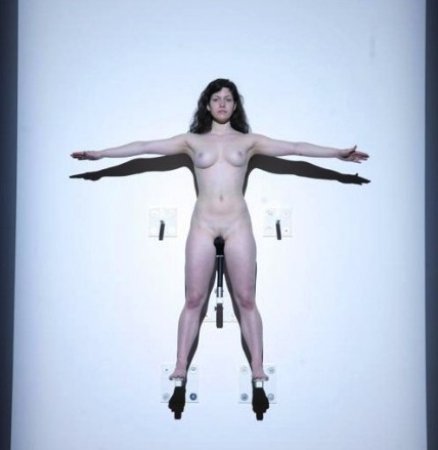

Bailey re-performing Marina Abramovic's

Luminosity

at MoMA (Photo courtesy of MoMA)

Bailey re-performing Marina Abramovic's

Luminosity

at MoMA (Photo courtesy of MoMA)

During my performances of Marina's work, I learned to stop thinking. This would sometimes take two hours to accomplish, and then finally, in the last few moments of the performance, I would really feel free from thinking. That felt good and appropriate, because there was so much happening in the room with the audience that I really wanted to engage with that instead of thinking about the granola I had for breakfast. I wanted to be as receptive as possible, and had the entire day every day the museum was open for three months to practice this. I tried not to take the time for granted.

Funny story: my mom came to stay with me and see the opening of Marina's show—I was the first to perform Luminosity —and when she woke up the day of the opening I was sitting on my fire escape, crying hard. She asked what was wrong, and I told her I had never practiced the performance—which entailed holding my arms out for over two hours, mounted 10 feet up on a wall, naked—and I didn't even know if I could do it. She laughed and pointed out that I had had all year to think about that. But she said it was just nerves, and I would be fine. She was right. When I got to the museum I decided I was going to get through this, and I did.

I learned from Marina that you do not need to rehearse, you just do it. The mind is what's hard to control, but the body is easy and very strong.

******

Bailey performing

Bailey performing

I think of the durational endurance aspect of my pieces as being more informative to my work than important. A 10-second dance that I may do for the clerks at the post office (which happened last Thursday) is just as important to me as a two-hour dance performance on a big stage.

Also, the durational, endurance aspect of my work is much longer and more intensive than what is seen in any of my pieces. Shaping my body sometimes requires months of constant attention to how I walk and the physical practices I involve myself in.

The information that comes to the surface when I hold a headstand or some other shape for more than a minute is usually, "Alright, let's move on to something else now." That's when I'm thinking. If I stop thinking and simply continue to feel, then usually I feel things like "Ow" or "Shit," which means maybe I need to take a breath and see where my body wants to shift to; the shift could be a leg or some organ re-situating itself inside of me, so I just have to wait and see where my body wants to go, and I allow for this. Soon after, a few other sensations rise to the surface, and eventually I settle into a shape.

Every day I try to find moments where everything is exactly where it should be, everything is perfect, and I can stay there forever. I believe time is subjective, and I try to create environments where it is okay to get lost in time.